Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

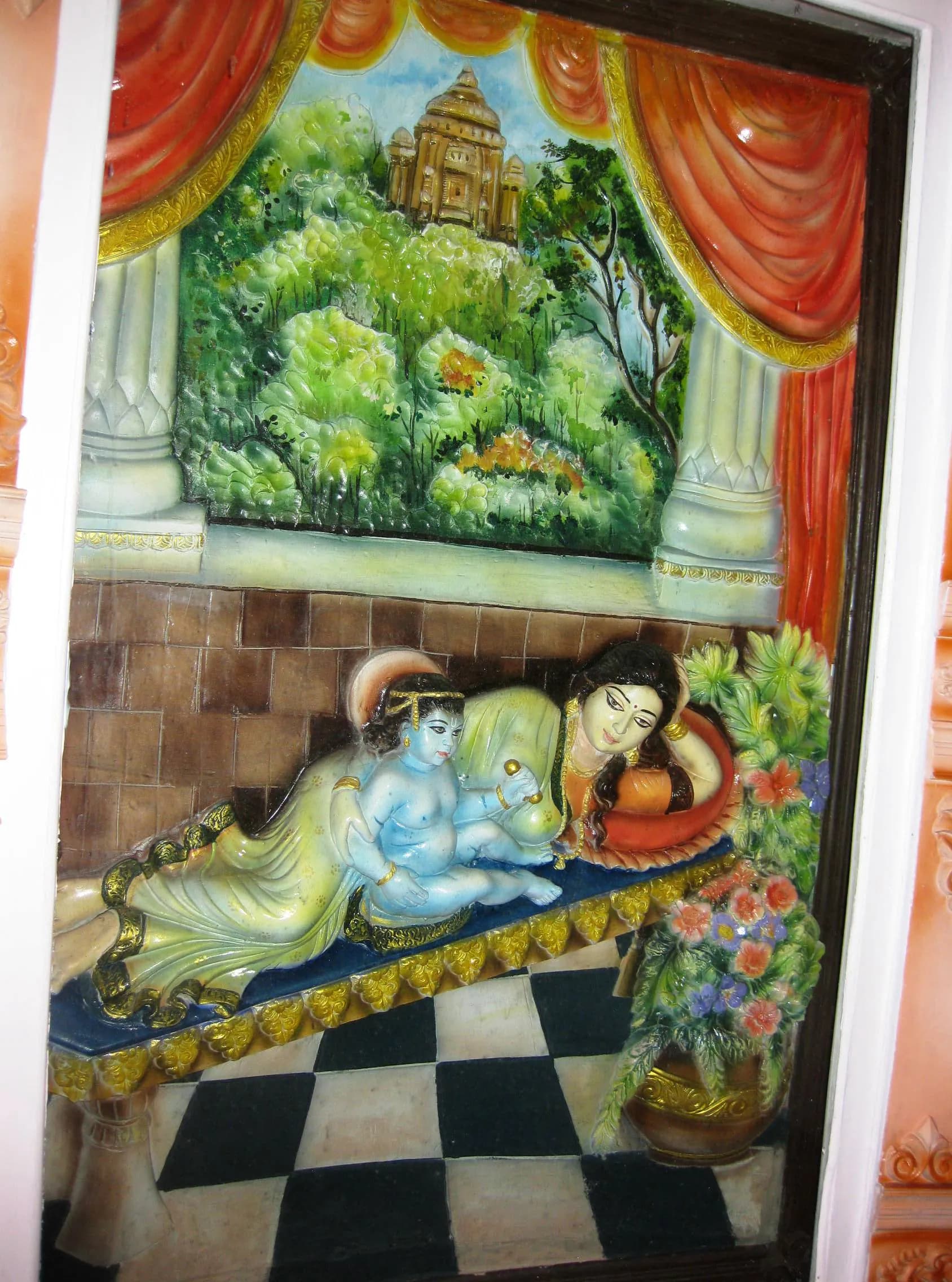

Sri Krishna Temple Udupi

The scent of incense hung heavy in the air, a fragrant welcome to the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha. Sunlight glinted off the ornate copper roof of the main temple, a vibrant splash of colour against the otherwise muted ochre walls. As a travel blogger who has traversed the length and breadth of India, documenting every UNESCO World Heritage site, I can confidently say that Udupi holds a unique charm, a spiritual resonance that sets it apart. It's not a UNESCO site itself, but its cultural and historical significance, deeply intertwined with the Dvaita philosophy of Madhvacharya, makes it a must-visit for anyone exploring India's rich heritage. Unlike the towering gopurams that dominate South Indian temple architecture, the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha is characterized by its relative simplicity. The exterior walls, while adorned with intricate carvings, maintain a sense of understated elegance. The real magic, however, lies within. One doesn't enter the sanctum sanctorum directly. Instead, devotees and visitors alike get a unique darshan of Lord Krishna through a small, intricately carved window called the "Kanakana Kindi." This nine-holed window, plated with silver, offers a glimpse of the deity, a tradition established by Madhvacharya himself. It's a powerful moment, a connection forged through a small aperture, yet brimming with spiritual significance. My visit coincided with the evening aarti, and the atmosphere was electrifying. The rhythmic chanting of Vedic hymns, the clang of cymbals, and the aroma of camphor filled the air, creating an immersive sensory experience. The courtyard, usually bustling with activity, fell silent as devotees lost themselves in prayer. Observing the rituals, the deep devotion etched on the faces of the worshippers, I felt a palpable sense of connection to centuries of tradition. The temple complex is more than just the main shrine. A network of smaller shrines dedicated to various deities, including Hanuman and Garuda, dot the premises. Each shrine has its own unique architectural style and historical narrative, adding layers of complexity to the overall experience. I spent hours exploring these smaller temples, each a testament to the rich tapestry of Hindu mythology. The intricate carvings on the pillars, depicting scenes from the epics, are a visual treat, showcasing the skill and artistry of the craftsmen who shaped this sacred space. One of the most striking features of the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha is the "Ashta Mathas," eight monasteries established by Madhvacharya. These Mathas, located around the main temple, play a crucial role in preserving and propagating the Dvaita philosophy. Each Matha has its own unique traditions and rituals, adding to the diversity of the religious landscape. I had the opportunity to interact with some of the resident scholars, and their insights into the philosophical underpinnings of the temple and its traditions were truly enlightening. Beyond the spiritual and architectural aspects, the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha also plays a significant role in the social and cultural fabric of the region. The temple kitchen, known for its delicious and hygienic meals, serves thousands of devotees every day. Witnessing the organized chaos of the kitchen, the sheer scale of the operation, was an experience in itself. It's a testament to the temple's commitment to serving the community, a tradition that has been upheld for centuries. Leaving the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha, I felt a sense of peace and fulfillment. It's a place where history, spirituality, and culture converge, creating an experience that is both enriching and transformative. While it may not yet bear the official UNESCO designation, its cultural significance is undeniable. It’s a testament to the enduring power of faith and tradition, a place that deserves to be on every traveller's itinerary.

Tiruchirapalli Fort Tiruchirapalli

The Rockfort, as it’s locally known, dominates the Tiruchirapalli skyline. Rising abruptly from the plains, this massive outcrop isn't just a fort, it's a layered testament to centuries of power struggles and religious fervor. My lens, accustomed to the sandstone hues of Madhya Pradesh, was immediately captivated by the stark, almost bleached, granite of this southern behemoth. The sheer scale of the rock itself is awe-inspiring, a natural fortress enhanced by human ingenuity. My climb began through a bustling marketplace that clings to the rock's lower slopes, a vibrant tapestry of daily life unfolding in the shadow of history. The air, thick with the scent of jasmine and spices, resonated with the calls of vendors and the chiming bells of the Sri Thayumanaswamy Temple, carved into the rock face. This temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, is an architectural marvel. The intricate carvings, some weathered smooth by time, others remarkably preserved, speak to the skill of the artisans who labored here centuries ago. The sheer audacity of excavating and sculpting such a complex within the rock itself left me speechless. Ascending further, I reached the Manikka Vinayagar Temple, dedicated to Lord Ganesha. The contrast between the two temples is striking. While the Shiva temple is a study in verticality, reaching towards the sky, the Ganesha temple feels more grounded, nestled within the rock's embrace. The vibrant colours of the gopuram, a stark contrast to the muted tones of the rock, add a touch of playful energy to the otherwise austere surroundings. The climb to the Upper Rockfort, where the remnants of the fort itself stand, is a journey through time. The steps, worn smooth by countless pilgrims and soldiers, are a tangible link to the past. As I climbed, I noticed the strategic placement of fortifications, the remnants of ramparts and bastions that once protected this strategic location. The views from the top are breathtaking, offering a panoramic vista of the city and the meandering Kaveri River. It's easy to see why this location was so fiercely contested throughout history, from the early Cholas to the Nayaks, the Marathas, and finally the British. The architecture of the fort itself is a blend of styles, reflecting the various dynasties that held sway here. I was particularly struck by the remnants of the Lalitankura Pallaveswaram Temple, a small, almost hidden shrine near the top. Its simple, elegant lines stand in stark contrast to the more ornate temples below, offering a glimpse into an earlier architectural tradition. Beyond the grand temples and imposing fortifications, it was the smaller details that truly captured my attention. The weathered inscriptions on the rock faces, the hidden niches housing small deities, the intricate carvings on pillars and doorways – these are the whispers of history, the stories that aren't found in textbooks. The experience of photographing the Rockfort was more than just documenting a historical site; it was a conversation with the past. The rock itself seemed to emanate a sense of timeless presence, a silent witness to the ebb and flow of human ambition and devotion. As I descended, leaving the towering rock behind, I carried with me not just images, but a profound sense of connection to a place where history, spirituality, and human ingenuity converge. The Rockfort is not just a fort; it is a living monument, a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit.

Bishnupur Terracotta Temples Bishnupur

Fired brick and mud brick construction techniques reached a zenith in Bishnupur, West Bengal, during the Bengal Renaissance period, as exemplified by its terracotta temples ([1][2]). These temples, constructed by the Malla dynasty who ruled from approximately the 7th to the 18th centuries CE ([3]), present a unique architectural style that blends classical Bengali forms with intricate terracotta artistry ([4]). The Malla kings, serving as patrons, facilitated the construction of these elaborate structures ([3]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls narrate stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and various Hindu Puranas, effectively bringing these ancient epics to life ([2][5]). The Jor Bangla temple, distinguished by its chala (hut-shaped) roof, is a prime example of this narrative tradition ([4]). The Rasmancha, commissioned by King Bir Hambir in the 17th century, provided a platform for displaying Radha-Krishna idols during the annual Ras festival ([3]). Stone platforms and foundations demonstrate the structural integrity of temples like the Madan Mohan Temple, which is further adorned with floral and geometric terracotta designs ([1][4]). Within the Garbhagriha (Sanctum), deities are enshrined, representing the focal point of devotion and architectural design ([2]). The Shyam Rai Temple, a pancharatna (five-pinnacled) structure, showcases a diverse range of themes, including scenes from courtly life alongside depictions of various deities ([2][5]). During the Bengal Renaissance period, temple architecture in Bishnupur achieved a distinctive aesthetic, where the terracotta medium lends a warm, intimate quality, creating a striking contrast to the grandeur often associated with stone structures found elsewhere in India ([1]). These temples not only served as places of worship but also as vibrant canvases that preserved and propagated cultural narratives for generations to come ([3][5]). The legacy of Bishnupur's terracotta temples remains a significant chapter in India's architectural heritage ([1][4]).

Sri Lakshmi Temple Ashland

Sri Lakshmi Temple in Ashland, Massachusetts, dedicated to Mahalakshmi and Lord Narayana, opens at 7:00 AM on weekdays and 6:00 AM on weekends, maintaining sequential abhishekams, archanas, and evening sahasranama chants until 8:30 PM across its granite mandapam and cultural center ([1][2]). Volunteer coordinators staff the heated entry plaza, shoe rooms, and vestibule during winter months, keeping queues orderly as visitors cycle between the main sanctum, subsidiary shrines, and the basement canteen ([1][3]). Security personnel coordinate with Ashland police during peak festivals, monitor snow-melt systems, and ensure emergency generators are ready for New England nor’easter outages ([3][5]). Elevators connect the mandapam to the cultural center and classrooms, ADA-compliant ramps ring the building, and ushers provide hearing-assist devices and closed-caption displays for Tamil and English liturgy ([1][4]). Custodians follow hourly schedules to wipe condensation, reset mats, and check radiant snow-melt manifolds, while HVAC zoning maintains steady temperatures despite Massachusetts winters ([3][5]). The temple’s computerized maintenance management system tracks priest schedules, life-safety inspections, and accessibility checks; 2025 Town of Ashland inspections recorded no outstanding violations, confirming mechanical, fire, and kitchen systems remain current ([3][4]).

Sri Thendayuthapani Temple Singapore

Sri Thendayuthapani Temple, built in 1859 by the Nattukottai Chettiars, anchors Tank Road as Singapore’s principal Murugan shrine and the culmination point for the annual Thaipusam kavadi pilgrimage ([1][2]). The temple’s five-tier rajagopuram features 3,500 polychromatic stucco figures and leads into a granite mandapa where Lord Murugan stands with Valli and Deivayanai beneath a gilded vimana. Daily worship begins 5:30 AM with Suprabhata Seva and closes at 9:00 PM with Arthajama Arati; multiple kala pujas, homa, and abhishekam are performed, especially during Thaipusam, Panguni Uttiram, and Skanda Shasti, when hundreds of kavadi bearers ascend the granite steps chanting “Vel Vel.” The temple precinct includes a newly constructed five-storey Annalakshmi Cultural Centre (2022) with banqueting halls, classrooms, dance studios, wellness suites, library, and the Annalakshmi vegetarian restaurant that funds charity initiatives. The Hindu Endowments Board manages annadhanam, Sikhara Veda classes, Carnatic music, Bharatanatyam, yoga, counselling, and senior outreach. Heritage tours, interfaith programmes, and research archives showcase the Chettiar community’s banking legacy, while disaster-relief fundraising, migrant welfare drives, and pandemic vaccination campaigns highlight the temple’s civic role. Integrated MEP systems, BMS controls, CCTV, and crowd management infrastructure enable the temple to support half a million visitors annually while conserving its historic Dravidian artistry ([1][3]).

City Palace Udaipur

The City Palace, Udaipur, situated in the historic city of Udaipur, Rajasthan, India, stands as a monumental testament to India's millennia-spanning cultural heritage and the continuous tradition of Indian civilization [1] [4]. This sprawling complex, built predominantly in indigenous Rajput architectural styles, with influences from Indo-Islamic, Haveli, and Maru-Gurjara traditions, reflects the deep historical roots and sophisticated craftsmanship of the region [1] [4]. Constructed primarily from granite and marble, the palace complex extends over an impressive facade of 244 meters (801 ft) in length and 30.4 meters (100 ft) in height, perched atop a ridge on the eastern bank of Lake Pichola . The structural system relies on robust marble and masonry, showcasing traditional Indian engineering prowess . The architectural details within the City Palace are extensive and intricate, featuring a fusion of courtyards, corridors, terraces, pavilions, and hanging gardens [1]. Specific features include elaborate mirror-work, delicate marble-work, vibrant murals, and intricate wall paintings, alongside silver-work and inlay-work . The Mor Chowk, or Peacock Courtyard, is particularly notable for its three-dimensional mosaic peacocks, crafted from 5,000 pieces of colored glass, representing the seasons of summer, winter, and monsoon . The Sheesh Mahal, or Palace of Mirrors, dazzles with its intricate mirror-work, while the Chini Chitrashala displays Chinese and Dutch ornamental tiles [1] . Defensive features are integrated into the design, such as zigzag corridors linking various palaces, intended to thwart surprise attacks . Water management systems, including fountains and pools like the one in Badi Mahal, provided cooling effects and were utilized for festivals such as Holi [1] . The City Palace Museum, housed within the Mardana Mahal and Zenana Mahal, actively preserves and displays royal artifacts, historic paintings, sculptures, and textiles, offering a glimpse into the royal lifestyle and cultural practices of the Mewar dynasty [4]. Conservation efforts are ongoing, with a state-of-the-art conservation laboratory established at the City Palace Museum, focusing on works on paper and aiming to become a regional training center [2]. A comprehensive Conservation Master Plan and Management Plan, funded by the Getty Foundation, guides future interventions and developments, emphasizing indigenous conservation techniques and an Indian perspective in international conservation . The site is fully operational, welcoming visitors to explore its historical grandeur, with guided tours available to enhance understanding of its rich heritage . The palace complex continues to serve as a vibrant cultural hub, hosting events and maintaining its legacy as a testament to India's enduring cultural continuum .

Phanom Rung Historical Park Buri Ram

Phanom Rung Historical Park, situated atop an extinct volcano 383 meters above sea level in Buri Ram Province, represents the most complete and architecturally sophisticated Khmer Hindu temple complex in Thailand, dedicated to Shiva as Bhadreshvara. The temple complex, constructed between the 10th and 13th centuries CE, spans approximately 60 hectares and features a meticulously planned east-west axis aligned precisely to capture the sunrise through all fifteen doorways during the equinoxes—a phenomenon that draws thousands of visitors annually. The main prasat (sanctuary tower) rises 27 meters, constructed from pink sandstone and laterite, accessed via a 160-meter-long processional walkway flanked by naga balustrades and punctuated by four cruciform gopuras. The complex includes three libraries, two ponds, and numerous subsidiary shrines, all demonstrating the evolution from Baphuon to Angkor Wat architectural styles. The temple’s lintels and pediments showcase exceptional bas-relief work depicting scenes from the Ramayana, Shiva’s cosmic dance, and various Hindu deities, with the famous Narai Bantomsin lintel considered among the finest examples of Khmer art. Archaeological excavations have revealed evidence of continuous use from the 10th century through the 15th century, with restoration work conducted by the Fine Arts Department of Thailand from 1971 to 1988, culminating in the site’s designation as a historical park in 1988. The temple remains an active site of worship during annual festivals, particularly during the Phanom Rung Festival in April, when traditional Brahmin ceremonies are performed. ([1][2])

Hanuman Tok Gangtok

The crisp mountain air, tinged with the scent of juniper and rhododendron, whipped around me as I stepped onto the platform of Hanuman Tok, a Hindu temple perched 3,500 feet above Gangtok. The panoramic vista that unfolded before me was simply breathtaking. The Kanchenjunga massif, its snow-capped peaks gleaming under the midday sun, dominated the horizon, a majestic backdrop to the vibrant prayer flags fluttering in the wind. This wasn't just a temple; it was a sanctuary woven into the very fabric of the Himalayan landscape. Hanuman Tok, meaning "Hanuman's shoulder," derives its name from a local legend. It is believed that Lord Hanuman, the revered monkey god of Hindu mythology, rested here momentarily while carrying the Sanjeevani herb from the Himalayas to Lanka to revive Lakshmana, as recounted in the epic Ramayana. This narrative imbues the site with a palpable sense of sacredness, a feeling amplified by the constant hum of chanting emanating from the temple. The temple itself is a relatively modern structure, built by the Indian Army, who also maintain the site. Its architecture, while not particularly ancient, reflects a blend of traditional Sikkimese and typical Hindu temple design. The vibrant colours – reds, yellows, and greens – stand out against the muted greens and browns of the surrounding hills. The sloping roof, reminiscent of Sikkimese architecture, is adorned with intricate carvings and colourful prayer flags. Inside, the main deity is Lord Hanuman, depicted in his familiar pose, a mace in hand, radiating strength and devotion. Unlike the elaborate ornamentation found in many temples of Uttar Pradesh, the interior here is relatively simple, the focus remaining firmly on the deity and the breathtaking views it commands. As I circumambulated the temple, turning the prayer wheels inscribed with mantras, I observed the diverse group of devotees. Sikkim, with its unique blend of Hinduism and Buddhism, fosters a spirit of religious harmony that is truly inspiring. I saw local Sikkimese families alongside tourists from mainland India, all united in their reverence for this sacred spot. Conversations in Nepali, Hindi, and English mingled with the rhythmic chanting, creating a vibrant tapestry of sound and faith. My upbringing in Uttar Pradesh, a land steeped in Hindu mythology and tradition, allowed me to connect with Hanuman Tok on a deeper level. While the architectural style differed from the grand temples of Varanasi or Ayodhya, the underlying devotion and reverence felt familiar. The stories of Lord Hanuman, ingrained in my consciousness from childhood, resonated even more powerfully against this majestic Himalayan backdrop. The experience wasn't just about the temple itself, but also about the journey to reach it. The winding road leading up to Hanuman Tok offered glimpses of the verdant valleys and terraced farms below, showcasing the harmonious co-existence of nature and human life. The vibrant prayer flags strung along the route, each one carrying a silent prayer to the wind, added to the spiritual ambience. Leaving Hanuman Tok, I carried with me more than just photographs and memories. I carried a sense of peace, a renewed appreciation for the power of faith, and a deeper understanding of how religious narratives intertwine with the landscape to create places of profound significance. The echoes of chanting, the crisp mountain air, and the majestic view of Kanchenjunga will forever remain etched in my mind, a testament to the spiritual richness of this Himalayan sanctuary.

Govind Dev Ji Temple Jaipur

The Govind Dev Ji Temple in Jaipur isn't just a place of worship; it's a living testament to a unique blend of architectural styles that captivated me from the moment I stepped within its precincts. Having spent years studying the Dravidian architecture of South Indian temples, I was eager to experience the distinct architectural vocabulary of this North Indian shrine, and I wasn't disappointed. Located within the City Palace complex, the temple almost feels like a private sanctuary for the royal family, a feeling amplified by its relatively modest exterior compared to the grandeur of the surrounding palace buildings. The first thing that struck me was the absence of the towering gopurams that define South Indian temple gateways. Instead, the entrance is marked by a series of chhatris, elevated, dome-shaped pavilions supported by ornate pillars. These chhatris, with their delicate carvings and graceful curves, speak to the Rajput influence, a stark contrast to the pyramidal vimanas of the South. The use of red sandstone, a hallmark of Rajasthani architecture, lends the temple a warm, earthy hue, quite different from the granite and sandstone palettes I'm accustomed to seeing in Tamil Nadu. As I moved through the courtyard, I observed the seven-storied structure housing the main shrine. While not a gopuram in the traditional sense, it does serve a similar function, drawing the eye upwards towards the heavens. The multiple stories, each adorned with arched openings and intricate jali work, create a sense of verticality and lightness, a departure from the solid mass of South Indian temple towers. The jalis, or perforated stone screens, not only serve as decorative elements but also allow for natural ventilation, a practical consideration in the arid climate of Rajasthan. The main sanctum, where the image of Govind Dev Ji (Krishna) resides, is a relatively simple chamber, its focus squarely on the deity. The absence of elaborate sculptures on the walls within the sanctum surprised me. South Indian temples often feature intricate carvings depicting mythological scenes and deities on every available surface. Here, the emphasis is on the devotional experience, a direct connection with the divine, unmediated by elaborate ornamentation. The silver-plated doors of the sanctum, however, are exquisitely crafted, showcasing the artistry of the region's metalworkers. The courtyard itself is a marvel of spatial planning. The open space allows for the free flow of devotees, while the surrounding colonnades provide shade and a sense of enclosure. The pillars supporting these colonnades are slender and elegant, adorned with intricate floral motifs and geometric patterns. I noticed a distinct Mughal influence in some of these decorative elements, a testament to the cultural exchange that shaped the region's artistic traditions. The use of marble for flooring, another Mughal influence, adds a touch of opulence to the space. One of the most captivating aspects of the Govind Dev Ji Temple is its integration with the City Palace. The temple's location within the palace complex blurs the lines between the sacred and the secular, reflecting the close relationship between the royal family and the deity. This integration is a departure from the South Indian tradition where temples, while often patronized by royalty, maintain a distinct identity as separate entities. My visit to the Govind Dev Ji Temple was a fascinating cross-cultural experience. It highlighted the diversity of India's architectural heritage and underscored the power of architecture to reflect regional identities and religious beliefs. While the temple's architectural vocabulary differed significantly from the Dravidian style I'm familiar with, the underlying spirit of devotion and the artistic skill evident in its construction resonated deeply with my understanding of sacred architecture.

San Phra Kan Prang Khaek Lopburi

San Phra Kan, also known as Prang Khaek, located in Lopburi town, represents the oldest Khmer Hindu shrine in Central Thailand, dating to the 9th-10th centuries CE and constructed during the early Angkorian period, likely during the reign of Suryavarman II. The temple complex features three brick prangs (towers) arranged in a row, dedicated to the Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, demonstrating the syncretic nature of early Khmer religious practice. The complex spans approximately 0.5 hectares and features a rectangular laterite enclosure wall, though much has been lost to urban development. The three prangs, constructed primarily from brick with sandstone doorframes and decorative elements, rise to heights between 10 and 12 meters, with the central tower being slightly taller. The temple’s architectural style represents early Angkorian period, predating the more elaborate Baphuon and Angkor Wat styles, featuring simpler decorative elements and construction techniques. The complex includes evidence of stucco decoration, though most has been lost to weathering. Archaeological evidence indicates the temple served as an important early Khmer religious center in Central Thailand, establishing the foundation for later Khmer architectural developments in the region. The site has undergone restoration since the 1930s, involving structural stabilization and conservation. Today, San Phra Kan remains an important site for understanding early Khmer architecture in Thailand, attracting visitors interested in its historical significance as the oldest Angkorian temple in Central Thailand and its role in establishing Khmer cultural influence in the region. ([1][2])

Tepe Narenj Monastery Kabul Afghanistan

Tepe Narenj, also known as Narenj Hill, rises dramatically from the southeastern outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan, preserving the extraordinary remains of a 5th to 7th century CE Buddhist monastery complex that represents one of the most significant and well-preserved examples of early medieval Buddhist architecture in Afghanistan, demonstrating the vibrant transmission of Indian Buddhist monastic traditions to Central Asia during a period when Buddhism flourished across the region under the patronage of various dynasties including the Hephthalites and early Turk Shahis. The monastery complex, constructed primarily from fired brick, stone, and stucco with extensive decorative elements, features a sophisticated multi-level architectural design that includes five small stupas arranged in a mandala pattern, five chapels with elaborate wall paintings and stucco sculptures, meditation cells, assembly halls, and water management systems, creating a complete monastic environment that reflects the transmission of Indian Buddhist architectural planning principles to Afghanistan. The site's architectural design demonstrates direct influence from Indian Buddhist monastery architecture, particularly the Gupta period styles found at sites like Nalanda and Ajanta, with the overall mandala-based plan, stupa forms, and decorative programs reflecting traditions that were systematically transmitted from India through centuries of cultural exchange, while the discovery of Tantric Buddhist iconography and practices provides crucial evidence of the transmission of advanced Indian Buddhist traditions to Afghanistan. Archaeological excavations have revealed extraordinary preservation of stucco sculptures, wall paintings, and architectural elements that demonstrate the sophisticated artistic traditions of the period, with the stucco work showing clear influence from Indian sculptural styles while incorporating local artistic elements, creating a unique synthesis that characterizes Gandharan and post-Gandharan Buddhist art in Afghanistan. The monastery was visited by the renowned Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang in the 7th century CE, who documented the site in his travel accounts, providing crucial historical evidence of the monastery's importance as a center of Buddhist learning and practice, while the site's location near Kabul underscores its role as a major religious center in the region. The monastery was likely destroyed during the 9th century CE following the decline of Buddhism in Afghanistan, but the substantial architectural remains that survive provide extraordinary evidence of the site's original grandeur and the sophisticated engineering techniques employed in its construction. Today, Tepe Narenj stands as a UNESCO Tentative List site and represents one of the most important archaeological discoveries in Afghanistan in recent decades, serving as a powerful testament to the country's ancient Buddhist heritage and its historical role as a center for the transmission of Indian religious and artistic traditions, while ongoing archaeological research continues to reveal new insights into the site's construction, religious practices, and cultural significance. ([1][2])

Sri Nagara Thandayuthapani Temple George Town Penang

Sri Nagara Thandayuthapani Temple (1850) stands adjacent to Penang Botanic Gardens, celebrated for its granite-carved mandapa of 60 pillars, barrel-vaulted roof, and intricately sculpted 23-metre rajagopuram added in 2012, making it one of Malaysia’s most ornate Murugan temples outside Batu Caves ([1][2]). Devotees ascend 82 steps lined with nangkol tamarind trees to reach the sanctum, which houses Murugan with Valli-Deivanayai, Surapadman effigies, and a golden vel. Temple opens 6:00 AM-9:30 PM with six puja cycles, weekly vel puja, and annadhanam; festivals include Skanda Shasti, Aadi Krithigai, Panguni Uttiram, and the Penang Thaipusam finale where devotees break coconuts and receive blessings. The compound features a marriage hall, cultural school, archive, vegetarian kitchen, counselling rooms, and community centre providing welfare assistance, scholarships, and disaster relief staging. The temple’s management (Nattukottai Chettiar trust) coordinates with Penang Island City Council for heritage tours, festival logistics, and sustainability initiatives such as rainwater harvesting, solar, composting, reforestation, and crowd control. The temple’s granite panel murals depict Murugan’s legends, while its archive holds 19th-century palm leaf documents detailing Chettiar guild activities ([1][3]).

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides