Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

Bhismaknagar Fort Roing

Fired brick and mud brick construction techniques define Bhismaknagar Fort, erected around 1100 CE by the Chutia kingdom in Arunachal Pradesh ([1][2]). As an archaeological site in Khatan, Lower Dibang Valley, Roing, it represents a significant example of Tai Ahom architectural influence ([3]). Archaeological excavations have uncovered a sophisticated, sprawling complex, revealing the architectural prowess of this medieval kingdom ([4]). The fort's rectangular layout features ramparts and gateways, constructed primarily from brick, showcasing the ingenuity of the builders ([5]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls display geometric and floral motifs, reflecting the cultural richness of the Chutia kingdom ([2]). Unlike typical stone fortifications, Bhismaknagar utilized locally abundant clay, crafting large bricks without mortar ([1][5]). Stone platforms and foundations demonstrate a planned construction, hinting at residential and administrative functions ([3][4]). The use of burnt brick, stone, timber, and bamboo highlights the resourcefulness of the builders ([1][2][3]). During the Ahom Period, temple architecture, though not fully evident in Bhismaknagar's ruins, likely influenced the fort's design ([5]). The architectural style incorporates elements of medieval design, with a focus on functionality and defense ([3][4]). Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, may have guided the layout and orientation of the fort, although specific textual references are not available ([5]). Bhismaknagar offers a glimpse into a forgotten era, a testament to the resilience and artistry of its creators ([1]). Bhismaknagar remains a significant archaeological site, linking us to India's diverse heritage ([2][3]). Further research and preservation efforts are crucial to understanding the full scope of its historical and architectural importance ([1][4]). The site stands as a reminder of the Chutia kingdom's legacy and their contribution to the region's cultural landscape ([2][5]).

Sri Sri Radha Radhanath Temple (Temple of Understanding)

Sri Sri Radha Radhanath Temple—popularly called the Temple of Understanding—opened in 1985 atop Chatsworth’s Lotus Park with a 56-metre triple-domed hall, mirrored ceiling panels, stained glass lotus windows, and marble balustrades that reinterpret classical Indian temple geometry for a modern South African skyline ([1][2]). The ISKCON complex houses the deities Sri Sri Radha Radhanath, Lord Jagannath Baladeva Subhadra, and Sri Sri Gaura-Nitai on a gold-leafed altar backed by Italian marble reliefs; devotees circumambulate beneath parabolic arches while chandeliers reflect across the glass mosaic vault. Daily worship begins 4:30 AM with mangala-arati and extends through twelve services culminating in night-time shayana arati accompanied by Durban’s signature kirtan ensembles. Beyond ritual, the 3.5-hectare campus functions as a social engine: a commercial-grade kitchen cooks up to 15,000 vegetarian meals weekly for the Food For Life programme, the Bhaktivedanta College offers spiritual education, yoga, counselling, and youth mentorship, and the Govinda’s restaurant and bakery anchor a vegetarian culinary tradition for the city. The temple’s amphitheatre hosts annual Festival of Chariots cultural productions, multi-faith dialogues, and classical Indian arts festivals broadcast worldwide via ISKCON's media network ([1][2]).

Dalverzin Tepe Surxondaryo Uzbekistan

Dalverzin Tepe, an ancient archaeological site located in the Surxondaryo Region of Uzbekistan, stands as a profound testament to the millennia-spanning cultural heritage of India, particularly through its embrace and adaptation of Indian Buddhist and Gandhara-Kushan architectural styles [3] [5]. This significant urban center, flourishing under the Kushan Empire, exemplifies the continuous tradition of Indian civilization's artistic and religious dissemination across Central Asia [2] [4]. The site's indigenous architectural styles, materials, and cultural practices reflect India's deep historical roots, showcasing a sophisticated synthesis of traditions [3]. The city plan of Dalverzin Tepe is characterized by a rectangular layout, featuring a prominent citadel at its core, with residential and religious structures meticulously arranged in parallel rows around this central defensive element [2]. Among its most significant features are two well-preserved Buddhist temples, which represent a direct extension of Indian Buddhist architectural principles into the region [4] [5]. These temples, constructed primarily from mud brick and pakhsa (rammed earth), demonstrate robust construction techniques typical of the period, often incorporating gypsum-coated clay for intricate sculptural and decorative elements [2] [3]. Archaeological excavations have unearthed numerous statues of Buddha and bodhisattvas, crafted from clay and gypsum, reflecting the distinctive Gandhara style that blends Hellenistic artistic conventions with Indian iconography [2] [4]. Specific architectural details include Attic stone column bases and terracotta antefixes, indicating a fusion of Greco-Roman and indigenous Central Asian elements, all serving to adorn structures dedicated to Indian religious practices [3]. A notable discovery is a gypsum-coated clay head of a youth, found within a Buddhist temple, which exemplifies the refined artistic output of the era [3]. The site also yielded a remarkable treasure hoard of gold, underscoring its historical wealth and cultural significance [2]. Dalverzin Tepe's urban planning included sophisticated defensive features, with the town experiencing active urban and defensive construction during its peak Kushan period [3]. While specific dimensions for individual structures are subject to ongoing research, the overall scale of the city suggests a well-organized settlement capable of sustaining a significant population and cultural activity [2]. The site is currently on the UNESCO Tentative List, recognizing its outstanding universal value and the need for continued preservation [1]. Ongoing archaeological findings, supported by joint excavations involving Uzbek, Korean, and Japanese scholars, contribute to a deeper understanding of its layered history and architectural evolution [4]. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing extant structures and protecting unearthed artifacts, ensuring the long-term preservation of this crucial link in India's cultural continuum [1]. The site is maintained for scholarly research and potential future public access, with current compliance and maintenance protocols in place to safeguard its heritage. Dalverzin Tepe stands as an enduring testament to India's profound and continuous cultural legacy, spanning thousands of years, and is operationally ready for continued study and eventual broader public engagement.

Yungang Grottoes Datong Shanxi China

The Yungang Grottoes, located in Yungang Town, Datong, Shanxi Province, China, stand as a monumental testament to the enduring legacy of Indian Buddhist art and its profound influence on East Asian cultural traditions, reflecting a continuous heritage spanning millennia [2] [3]. This UNESCO World Heritage Site comprises 252 caves and niches, housing over 51,000 statues carved into the sandstone cliffs, extending for approximately one kilometer along the Wuzhou Mountains [1] . The architectural style is deeply rooted in Gandhara-influenced and Indian rock-cut traditions, which were transmitted along the ancient Silk Road [2] [4]. The earliest and most significant phase of construction, known as the 'Tanyao Five Caves' (Caves 16-20), initiated around 460 CE, showcases colossal Buddha figures that adhere closely to the iconic forms developed in Gandhara, a significant Buddhist center in ancient northwestern India [2] [3]. These monumental Buddhas, such as the central seated figure in Cave 20, which measures approximately 13 meters in height, exhibit distinct Indian stylistic elements including plump cheeks, thick necks, elongated eyes, and robes that cling tightly to the body, rendered with schematic patterns [2] . The right shoulder of the main Buddha in Cave 20 is exposed, a characteristic feature of early Indian Buddhist iconography [2]. The structural elements within the grottoes often feature central pillars, a design adapted from Indian chaityas (sanctuary or prayer halls) found in sites like the Ajanta Caves in India, though at Yungang, these pillars frequently incorporate Chinese gable roofs [3] . The caves are carved directly into the natural rock, utilizing the local sandstone as the primary material. Decorative elements are rich and varied, including flame patterns and miniature seated Buddhas within the halos, as well as flying apsaras, lotuses, and honeysuckle motifs [1] [5]. The honeysuckle patterns, in particular, demonstrate influences from Greco-Roman art, filtered through Indian and Central Asian traditions, highlighting the multicultural integration at the site [5]. Cave 6, for instance, features an antechamber and a square main chamber supported by a central pillar, with walls divided into three vertical registers depicting scenes from the Buddha's life, such as the First Sermon at Deer Park, identifiable by deer carved on the Buddha's throne [2]. Technical details include the careful excavation of the caves to create vast interior spaces, some designed to accommodate thousands for Buddhist activities, as seen in the original design of Cave 3 . Currently, the Yungang Grottoes are subject to extensive conservation efforts, including advanced digital preservation techniques . Since 2003, high-precision 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry have been employed to create detailed digital models, ensuring comprehensive documentation and facilitating archaeological research and virtual exploration . The Yungang Grottoes Research Academy, in collaboration with various universities, has established the Digital Yungang Joint Laboratory to further these efforts, including the production of full-size 3D-printed replicas of caves, such as Cave 3 (17.9m x 13.6m x 10.0m) and Cave 18 (17 meters high), for exhibition and public education . These replicas, constructed from nearly 1000 3D-printed blocks reinforced with polymer materials and custom-lacquered to match the original stone, demonstrate innovative approaches to heritage dissemination . Ongoing physical conservation addresses threats such as water seepage, rain erosion, and weathering, with interventions adhering to principles of minimal impact [1] . The site is fully operational, offering visitor access to the grottoes and engaging programming, while maintaining strict compliance with international heritage preservation standards [1] .

Khammam Fort Khammam

The imposing silhouette of Khammam Fort against the Telangana sky held me captive long before I even reached its gates. The laterite stone, baked to a deep, earthy red by centuries of sun, seemed to pulse with stories whispered down through generations. My journey as a heritage photographer has taken me to many magnificent sites across Madhya Pradesh, but Khammam Fort, with its unique blend of architectural styles, held a particular allure. The fort's strategic location atop a hillock overlooking the city was immediately apparent. Built in 950 AD by the Kakatiya dynasty, it bore witness to the rise and fall of several empires – from the Qutb Shahis to the Mughals and finally, the Asaf Jahis of Hyderabad. This layered history was etched into the very fabric of the structure. Passing through the imposing main gate, I was struck by the contrast between the rough-hewn exterior and the intricate details within. The massive granite pillars, some intricately carved, others bearing the scars of time and conflict, spoke volumes about the fort's enduring strength. I spent hours exploring the various sections, each revealing a different chapter of the fort's story. The remnants of the Kakatiya-era architecture were particularly fascinating. The stepped wells, or *bawdis*, were marvels of engineering, showcasing the ingenuity of the ancient builders in water harvesting. The intricate carvings on the pillars and lintels, though weathered, still hinted at the grandeur of the Kakatiya period. I was particularly drawn to the remnants of a temple dedicated to Lord Shiva, its sanctum sanctorum now open to the sky, the stone worn smooth by the elements. The influence of subsequent rulers was also evident. The Qutb Shahi period saw the addition of mosques and palaces, their arched doorways and intricate stucco work a stark contrast to the earlier, more austere Kakatiya style. The Mughal influence was subtle yet discernible in the layout of certain sections, particularly the gardens, which, though now overgrown, still hinted at a formal, structured design. One of the most captivating aspects of Khammam Fort was its integration with the natural landscape. The fort walls seemed to grow organically from the rocky outcrop, the laterite stone blending seamlessly with the surrounding terrain. From the ramparts, the panoramic view of the city and the surrounding countryside was breathtaking. I could almost imagine the sentinels of old, keeping watch from these very walls, their gaze sweeping across the landscape. As I moved through the fort's various chambers, I noticed the intricate system of tunnels and secret passages. These subterranean routes, once used for escape or strategic movement during times of siege, now lay silent, their darkness holding secrets untold. Exploring these passages, I felt a palpable sense of history, a connection to the lives lived within these walls. My lens captured the grandeur of the fort, the intricate details of its architecture, and the breathtaking views from its ramparts. But beyond the visual documentation, I felt a deeper connection to the site. Khammam Fort wasn't just a collection of stones and mortar; it was a living testament to the resilience of human spirit, a repository of stories waiting to be discovered. The echoes of its past resonated within its walls, a reminder of the ebb and flow of empires, the enduring power of human ingenuity, and the beauty that emerges from the confluence of history and nature. Leaving Khammam Fort, I carried with me not just photographs, but a profound sense of awe and a deeper understanding of the rich tapestry of India's heritage.

Bala Hanuman Mandir Jamnagar

The Bala Hanuman Mandir in Jamnagar, Gujarat, resonates with the continuous chanting of "Sri Ram, Jai Ram, Jai Jai Ram" since 1964, a feat recognized by the Guinness World Records ([1][2]). This 20th-century temple, built during the British Colonial Period, stands as a testament to unwavering devotion and community spirit ([2][3]). While not adhering to strict UNESCO architectural guidelines, its design incorporates regional materials and vernacular styles, reflecting the local Gujarati traditions ([4]). Dedicated to Lord Hanuman, the temple provides a serene space for devotees. Within the Garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), a vibrant idol of Lord Hanuman, adorned in traditional orange robes, captivates the eye ([4]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls depict scenes from the Ramayana, enriching the temple's spiritual ambiance ([5]). The continuous chanting, a form of devotional practice known as 'Ajapa Japa', creates a powerful spiritual atmosphere ([1]). During the British Colonial Period, the Bala Hanuman Mandir served as a focal point for the local community, fostering a sense of unity and shared faith ([3]). Stories abound of devotees finding solace and connection within its walls ([1]). Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, may have subtly influenced the temple's layout, promoting harmony and positive energy, though specific textual references are currently undocumented. Leaving the Bala Hanuman Mandir, visitors carry with them a profound sense of collective devotion, a reminder of the enduring power of faith ([2][5]). The temple's simple yet resonant structure provides a compelling glimpse into the region's religious practices and cultural heritage ([3][4]).

Sringeri Sharadamba Temple Sringeri

The Sharadamba Temple at Sringeri, nestled within the verdant embrace of the Western Ghats, exudes an aura of timeless serenity. The temple, dedicated to the goddess of learning, Sharada, isn't just a structure of stone and wood; it's a living testament to centuries of devotion and scholarship. My recent visit, as a heritage photographer from Madhya Pradesh, felt less like a documentation and more like a pilgrimage. The current temple, rebuilt in the 1910s after a fire, retains the essence of the original structure envisioned by Adi Shankaracharya in the 8th century. While the earlier structure was primarily wooden, the present temple incorporates Hoysala and Dravidian architectural elements, creating a unique blend of styles. The towering gopuram, though a later addition, commands attention with its intricate carvings of deities and mythical creatures. It acts as a vibrant gateway to the serene courtyard within. Stepping inside, I was immediately drawn to the Vidyashankara Temple, a 14th-century marvel dedicated to Lord Shiva. This architectural gem, built during the Vijayanagara period, stands on a raised platform with intricately carved granite pillars depicting various incarnations of Vishnu. The fusion of Hoysala and Dravidian styles is particularly evident here, with the ornate pillars and detailed friezes showcasing a remarkable level of craftsmanship. I spent hours photographing the intricate details – the delicate floral patterns, the expressive figures of gods and goddesses, and the mesmerizing geometric designs. The play of light and shadow on the stone surfaces added another layer of depth to the visual narrative. The main shrine of Sharadamba, however, is the heart of the temple complex. The goddess, seated gracefully on a golden throne, radiates an aura of profound peace and wisdom. The sandalwood idol, adorned with exquisite jewellery, is a masterpiece of devotional art. Unlike the imposing grandeur of the Vidyashankara Temple, the Sharadamba shrine exudes a quiet elegance. The focus remains firmly on the goddess, inviting contemplation and introspection. I found myself captivated by the simplicity and purity of the space, a stark contrast to the ornate surroundings. The temple complex also houses a library, a testament to Sringeri's historical significance as a center of learning. While I couldn't access the ancient texts, the very presence of this library underscored the temple's role in preserving and propagating knowledge. The atmosphere within the complex was charged with a palpable sense of devotion and scholarship, a feeling that permeated every corner, from the bustling courtyard to the quiet corners of the library. One of the most striking aspects of the Sringeri Sharadamba Temple is its seamless integration with the surrounding landscape. The Tunga River, flowing gently beside the temple, adds to the tranquil atmosphere. I spent some time by the riverbank, observing the devotees performing rituals and taking in the breathtaking views of the surrounding hills. The natural beauty of the location enhances the spiritual significance of the temple, creating a harmonious blend of the divine and the earthly. My experience at Sringeri wasn't just about capturing images; it was about immersing myself in the rich history and spiritual significance of the place. The temple isn't merely a static monument; it's a vibrant hub of religious and cultural activity. The chanting of Vedic hymns, the fragrance of incense, and the constant flow of devotees created a dynamic atmosphere that was both captivating and humbling. As a heritage photographer, I felt privileged to witness and document this living heritage, a testament to the enduring power of faith and tradition. The images I captured, I hope, will convey not just the architectural beauty of the temple, but also the profound spiritual experience it offers.

Multan Sun Temple Ruins Multan

The midday sun beat down on the dusty plains of Multan, casting long shadows across the uneven ground where the magnificent Multan Sun Temple once stood. Now, only fragmented remnants whisper tales of its former glory. As someone who has explored the intricate cave temples of Ajanta and Ellora, the robust rock-cut shrines of Elephanta, and the serene beauty of Karla Caves, I felt a pang of both familiarity and sadness standing amidst these ruins. While Maharashtra’s temples are testaments to enduring faith, the Multan Sun Temple stands as a poignant reminder of the fragility of heritage. The site, locally known as the Prahladpuri Temple, is believed to have been dedicated to the sun god Surya, though some scholars associate it with Aditya. Unlike the basalt structures I’m accustomed to in Maharashtra, this temple was primarily built of brick, a common building material in the Indus Valley region. The baked bricks, now weathered and crumbling, still bear the marks of intricate carvings, hinting at the elaborate ornamentation that once adorned the temple walls. I could discern traces of floral motifs, geometric patterns, and what appeared to be depictions of celestial beings, echoing the decorative elements found in some of Maharashtra's Hemadpanti temples. The sheer scale of the ruins is impressive. Scattered mounds of brick and debris suggest a structure of considerable size, possibly a complex of shrines and ancillary buildings. Local narratives speak of a towering temple, its shikhara reaching towards the heavens, covered in gold and glittering in the sunlight. While the gold is long gone, and the shikhara reduced to rubble, the energy of the place is palpable. I closed my eyes, trying to envision the temple in its prime, the chants of priests resonating, the air thick with the scent of incense, and the sun’s rays illuminating the golden spire. One of the most striking features of the site is the presence of a large, rectangular tank, possibly used for ritual ablutions. This reminded me of the stepped tanks found in many ancient temples across India, including those in Maharashtra. The tank, though now dry and filled with debris, speaks volumes about the importance of water in religious practices. I noticed remnants of what seemed like a drainage system, showcasing the advanced engineering knowledge of the time. Walking through the ruins, I stumbled upon several carved fragments, likely pieces of pillars or door frames. The intricate details on these fragments were astonishing. I recognized influences from various architectural styles, including elements reminiscent of Gandhara art, which blended Greco-Roman and Indian aesthetics. This fusion of styles is a testament to Multan's historical position as a crossroads of civilizations. It was fascinating to see how different artistic traditions had converged in this one place, much like the confluence of architectural styles seen in some of the later temples of Maharashtra. The destruction of the Multan Sun Temple is shrouded in historical accounts, attributed to various invaders over the centuries. While the exact circumstances remain debated, the loss of such a magnificent structure is undoubtedly a tragedy. Standing amidst the ruins, I couldn't help but draw parallels to the damage inflicted on some of Maharashtra's temples during periods of conflict. However, unlike many of the damaged temples in Maharashtra, which were later restored, the Multan Sun Temple remains in ruins, a stark reminder of the destructive power of time and human actions. My visit to the Multan Sun Temple was a deeply moving experience. While the physical structure is largely gone, the spirit of the place persists. The ruins whisper stories of a glorious past, of devotion, artistry, and cultural exchange. It serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of preserving our shared heritage, not just in Maharashtra, but across the subcontinent and beyond. These fragmented remnants are more than just bricks and stones; they are fragments of history, waiting to be understood and appreciated.

Yaganti Temple Kurnool

The air hung thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of chanting as I approached the Yaganti temple, nestled in the Nallamalla hills of Andhra Pradesh. Hewn from the living rock, the monolithic marvel rose before me, an ode to the Vishwakarma sthapathis who sculpted it from a single granite boulder. Unlike the elaborate, multi-tiered structures common in South Indian temple architecture, Yaganti possesses a stark, almost primal beauty. The main shrine, dedicated to Sri Yaganti Uma Maheswara Swamy, felt anchored to the earth, exuding a sense of timeless stability. My gaze was immediately drawn to the intricate carvings adorning the temple walls. While some panels depicted scenes from the epics – the Ramayana and Mahabharata – others showcased a fascinating blend of Shaiva and Vaishnava iconography, a testament to the region's rich and syncretic religious history. I noticed the distinct lack of mortar; the stones, fitted together with astonishing precision, spoke volumes about the advanced architectural knowledge prevalent during the Vijayanagara period, to which significant portions of the temple are attributed. Inside the dimly lit sanctum, the air was heavy with devotion. The lingam, naturally formed and perpetually moist, is a unique feature of Yaganti. Local legend attributes this to a subterranean spring and links it to the temple's name, 'Yaganti,' derived from 'Agastya' and 'ganti' – the bell of Agastya, the revered sage. While the scientific explanation points to capillary action drawing moisture from the surrounding rock, the aura of mystique surrounding the lingam was undeniable. Stepping out into the sunlight, I explored the Pushkarini, a sacred tank located within the temple complex. The water, remarkably clear and cool even under the midday sun, is believed to possess healing properties. Observing the devotees taking a ritual dip, I was struck by the continuity of tradition, a living link to centuries past. The architecture surrounding the Pushkarini, while simpler than the main temple, displayed a similar attention to detail. The stepped ghats, carved from the same granite bedrock, seamlessly integrated the tank into the natural landscape. Further exploration revealed the remnants of earlier architectural phases. The influence of the Badami Chalukyas, who are believed to have laid the foundation of the temple, was evident in certain stylistic elements, particularly in the older sections of the complex. This layering of architectural styles, from the early Chalukyan period to the later Vijayanagara additions, provided a tangible record of the temple's evolution over centuries. One of the most striking features of Yaganti is the unfinished Nandi, located a short distance from the main temple. This colossal monolithic bull, still partially attached to the bedrock, offers a glimpse into the arduous process of sculpting these monumental figures. The sheer scale of the unfinished Nandi, coupled with the precision of the already completed portions, left me in awe of the skill and dedication of the ancient artisans. As I left Yaganti, the image of the monolithic temple, rising from the earth like an organic outgrowth, remained etched in my mind. It was more than just a structure; it was a testament to human ingenuity, a repository of cultural memory, and a living embodiment of faith. The experience transcended mere observation; it was a journey through time, a dialogue with the past, and a profound reminder of the enduring power of art and architecture.

Reis Magos Fort Panaji

The laterite ramparts of Reis Magos Fort, bathed in the Goan sun, seemed to emanate a quiet strength, a testament to their enduring presence. Perched strategically at the mouth of the Mandovi River, the fort’s reddish-brown walls contrasted sharply with the vibrant green of the surrounding foliage and the dazzling blue of the Arabian Sea beyond. My visit here wasn't just another stop on my architectural journey; it was a palpable connection to a layered history, a whispered conversation with the past. Unlike many of the grander, more ornate forts I’ve explored across India, Reis Magos possesses a distinct character of understated resilience. Built in 1551 by the Portuguese, it served primarily as a protective bastion against invaders, a role mirrored in its robust, functional design. The walls, though not excessively high, are remarkably thick, showcasing the practical approach to defense prevalent in the 16th century. The laterite, a locally sourced material, lends the fort a unique earthy hue, seamlessly blending it with the Goan landscape. This pragmatic use of local resources is a hallmark of many ancient Indian structures, a testament to the ingenuity of the builders. Ascending the narrow, winding staircase within the fort, I was struck by the strategic placement of the gun embrasures. These openings, carefully positioned to offer a commanding view of the river, spoke volumes about the fort's military significance. The views from the ramparts were breathtaking, offering a panoramic vista of the Mandovi River merging with the sea, dotted with fishing boats and modern vessels. It was easy to imagine the Portuguese sentinels scanning the horizon for approaching enemies, the fort serving as their vigilant guardian. The architecture within the fort is relatively simple, devoid of the elaborate carvings and embellishments often found in Mughal or Rajput structures. The focus here was clearly on functionality and defense. The chapel, dedicated to the Three Wise Men (Reis Magos), is a small, unassuming structure, yet it holds a quiet dignity. The stark white walls and the simple altar offer a peaceful respite from the martial atmosphere of the fort. The interplay of light filtering through the small windows created an ethereal ambiance, a stark contrast to the robust exterior. One of the most intriguing aspects of Reis Magos is its layered history. Having served as a prison during the Portuguese era and later under the Indian government, the fort carries within its walls echoes of both confinement and resilience. The restoration work, undertaken meticulously in recent years, has breathed new life into the structure while preserving its historical integrity. The addition of a small museum within the fort further enhances the visitor experience, showcasing artifacts and providing valuable insights into the fort's rich past. As I descended from the ramparts, I couldn't help but reflect on the enduring power of architecture to tell stories. Reis Magos Fort, though smaller and less ostentatious than many of its counterparts, speaks volumes about the strategic importance of Goa, the ingenuity of its builders, and the ebb and flow of history. It's a place where the past and present intertwine, offering a unique and enriching experience for anyone seeking to connect with the rich tapestry of Indian history. The fort stands not just as a relic of a bygone era, but as a living testament to the enduring spirit of Goa. It's a place that stays with you long after you've left, a quiet reminder of the stories whispered within its ancient walls.

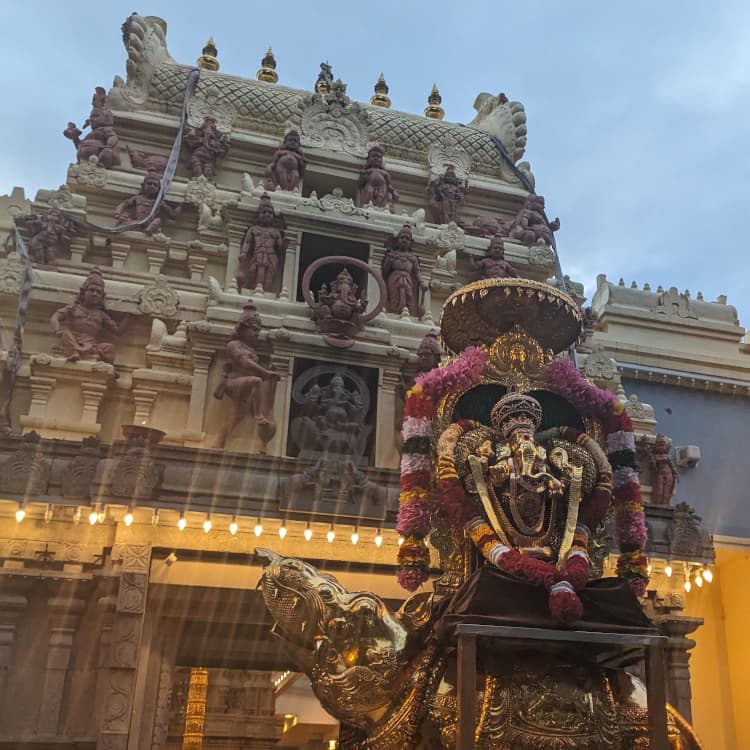

Sri Vakrathunda Vinayagar Temple The Basin

Sri Vakrathunda Vinayagar Temple The Basin is dedicated to Lord Ganesha and anchors The Basin, Victoria, on the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges ([1][2]). The hilltop mandir opens daily 6:00 AM-12:00 PM and 4:00 PM-8:30 PM, with Vinayagar Chathurthi and Thai Poosam schedules extending to 10:30 PM; marshals in high-visibility vests coordinate shuttle buses from the lower car park to keep the single-lane driveway clear ([1][4]). Mandapa floor markings separate pradakshina loops from queue lanes, and RFID counters at the entry tally pilgrim volumes so the volunteer command post can pace access into the sanctum ([1][5]). Annadhanam is served from a timber-lined dining hall with polished concrete floors, commercial dishwashers, and induction woks to reduce bushfire risk by avoiding naked flames ([1][3]). A 1:16 timber ramp with anti-slip mesh runs along the southern retaining wall, linking the car park to the mandapa, while stainless handrails, tactile paving, and hearing loop signage support inclusive access ([2]). Bushfire-ready shutters, ember screens, and a 90,000-litre tank plumbed to rooftop drenchers stand ready each summer, with CFA volunteers drilling annually alongside temple wardens ([2][5]). Wayfinding boards highlight refuge zones, first aid, and quiet meditation groves along the eucalyptus ridge, and QR codes push live updates about weather, kangaroo movement, and shuttle schedules directly to visitor phones ([1][6]). With emergency protocols rehearsed, food safety plans audited, and musician rosters published weeks ahead, the temple remains fully prepared for devotees, hikers, and school excursions seeking the hilltop shrine ([1][2]).

Burana Tower Complex Tokmok Kyrgyzstan

Rising dramatically from the Chui Valley, the Burana Tower, situated near Tokmok, Kyrgyzstan, marks the site of the ancient city of Balasagun ([1][2]). Constructed around 850 CE by the Karakhanid Khanate, this medieval minaret reflects Indian architectural influences along the Silk Road ([1]). Although originally reaching 45 meters, earthquake damage has reduced the tower to a height of 25 meters, yet it remains a significant cultural symbol ([1]). Fired brick and mud brick construction techniques, incorporating stone, lime mortar, metal, and wood, highlight advanced engineering practices ([1][2]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls and the tower's tapering form echo design principles similar to those in ancient Indian architecture ([1]). These elements suggest a transmission of knowledge, mirroring the *Shikhara* (spire) design found in Indian temples, indicative of the broader transmission of Indian architectural knowledge ([1][2]). The influence of *Vastu Shastra* principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, can be observed in the tower's layout and proportions, suggesting a deliberate integration of Indian design concepts ([3]). Archaeological excavations have uncovered artifacts, including Buddhist sculptures, further illustrating the site's role as a nexus of trade and cultural exchange ([1][2][4]). This synthesis of Indian architectural traditions with local Central Asian aesthetics underscores the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian architectural development, showcasing the interconnectedness of these regions during the medieval period ([1][2]). The tower's design incorporates elements reminiscent of the *Mandapa* (pillared hall) concept, adapted to suit the tower's function ([5]). The Burana Tower stands as a crucial landmark, exemplifying the transmission of architectural and cultural ideas across continents ([4][5]). Its existence highlights the interconnectedness of cultures along the Silk Road and the lasting impact of Indian architectural and artistic traditions on the broader Central Asian region ([3][4]).

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides