Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

Swaminarayan Akshardham Gandhinagar

The first glimpse of the Swaminarayan Akshardham Temple in Gandhinagar stopped me in my tracks. Emerging from the meticulously manicured gardens, the temple complex, a symphony in pink sandstone and Italian Carrara marble, felt less like a structure and more like a sculpted dream. Having spent years documenting the ancient temples of Madhya Pradesh, I thought I was prepared for the grandeur of Akshardham, but the sheer scale and intricate detail surpassed all expectations. The sun, already high in the Gujarat sky, kissed the ornate carvings that covered every inch of the temple’s exterior. It was as if an army of artisans had dedicated lifetimes to etching narratives from Hindu scriptures, epics, and mythology onto the stone. Deities, celestial musicians, dancers, flora, and fauna – a breathtaking panorama of life and devotion unfolded before my lens. I found myself constantly shifting position, trying to capture the interplay of light and shadow on the deeply carved surfaces, the way the sun highlighted a particular expression on a deity's face or the delicate tracery of a floral motif. Stepping inside the main mandir, the experience shifted from visual opulence to a palpable sense of serenity. The vast, pillared halls, despite the throngs of visitors, held a quiet reverence. The central chamber, housing the murti of Bhagwan Swaminarayan, radiated a golden glow. The intricate detailing continued within, with carved pillars depicting different avatars and scenes from Hindu lore. I spent a considerable amount of time simply observing the devotees, their faces etched with devotion as they offered prayers. It was a powerful reminder of the living faith that breathed life into these magnificent stones. Beyond the main temple, the complex unfolded like a meticulously planned narrative. The exhibition halls, employing a fascinating blend of traditional artistry and modern technology, brought to life the teachings and life of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. Dioramas, animatronics, and immersive displays transported me to different eras, allowing me to witness key moments in his life and understand the philosophy he espoused. As a photographer accustomed to capturing static moments in time, I was particularly impressed by the dynamic storytelling employed in these exhibits. The surrounding gardens, a sprawling oasis of green, provided a welcome respite from the intensity of the temple architecture. The meticulously manicured lawns, punctuated by fountains and reflecting pools, offered a tranquil setting for contemplation. The evening water show, a spectacular symphony of light, sound, and water jets, was a fitting culmination to the day. Projected onto a massive water screen, the story of India's cultural heritage unfolded in vibrant colours and captivating choreography. What struck me most about Akshardham was not just its architectural magnificence, but the palpable sense of harmony that permeated the entire complex. From the intricate carvings on the temple walls to the serene gardens and the technologically advanced exhibitions, every element seemed to work in concert to create a holistic experience. It was a testament to the dedication and vision of the countless individuals who contributed to its creation. As a heritage photographer, I have visited numerous ancient sites across Madhya Pradesh and beyond. Each place holds its own unique charm and historical significance. But Akshardham stands apart. It is not merely a temple; it is a living testament to the enduring power of faith, art, and culture. It is a place where tradition meets modernity, where spirituality intertwines with technology, and where the past and present converge to create an experience that is both awe-inspiring and deeply moving. Leaving the illuminated complex behind, I carried with me not just photographs, but a profound sense of wonder and a renewed appreciation for the rich tapestry of Indian heritage.

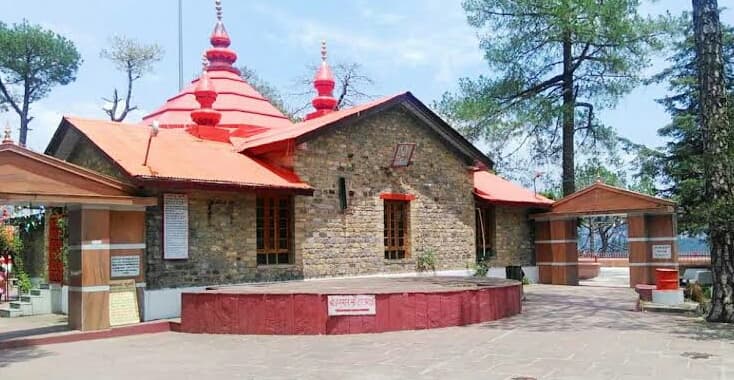

Sankat Mochan Temple Shimla

The crisp Shimla air, scented with pine and a hint of something sweeter, perhaps incense, drew me deeper into the vibrant embrace of the Sankat Mochan Temple. Nestled amidst the deodar-clad hills, overlooking the sprawling town below, the temple stands as a testament to faith and architectural ingenuity. Coming from Uttar Pradesh, a land steeped in its own rich tapestry of temples, I was curious to see how this Himalayan shrine would compare. The first thing that struck me was the temple's relative modernity. Built in the 1950s, it lacks the ancient patina of the temples I'm accustomed to back home. Yet, it possesses a distinct charm, a vibrancy that comes from being a living, breathing space of worship. The bright orange and yellow hues of the temple, set against the deep green of the surrounding forest, create a striking visual contrast. The architecture is a fascinating blend of North Indian and Himachali styles. The multi-tiered sloping roofs, reminiscent of traditional Himachali houses, are adorned with intricate carvings and colourful embellishments. The main entrance, however, features a distinctly North Indian archway, perhaps a nod to the deity enshrined within. The temple is dedicated to Lord Hanuman, the revered monkey god, a figure deeply embedded in the cultural consciousness of both Uttar Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. Inside the main sanctum, a large, imposing statue of Hanuman dominates the space. The deity is depicted in his characteristic pose, hands folded in reverence, his orange fur gleaming under the soft glow of the lamps. The air inside is thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers. Devotees from all walks of life, locals and tourists alike, thronged the temple, their faces etched with devotion. I observed a quiet reverence in their actions, a palpable sense of connection with the divine. Unlike the often elaborate rituals and ceremonies I've witnessed in Uttar Pradesh temples, the worship here seemed simpler, more direct. There was a quiet intimacy to the devotees' interactions with the deity, a sense of personal connection that transcended elaborate rituals. This, I felt, was the true essence of the temple – a space where individuals could connect with their faith in their own way, without the pressure of prescribed practices. Stepping out of the main sanctum, I explored the temple complex further. A large courtyard, paved with stone, offered stunning panoramic views of the valley below. The snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas loomed in the distance, adding a majestic backdrop to the vibrant scene. Smaller shrines dedicated to other deities dotted the courtyard, each with its own unique character and following. I noticed a small shrine dedicated to Lord Rama, Hanuman's beloved master, a testament to the enduring bond between the two figures. The presence of langurs, the grey-faced monkeys considered sacred in Hinduism, added another layer to the temple's unique atmosphere. They roamed freely within the complex, seemingly unfazed by the human activity around them. Their presence, I realized, was more than just a charming quirk; it was a tangible link to the deity enshrined within, a reminder of Hanuman's own simian form. As I descended the steps of the Sankat Mochan Temple, I carried with me more than just memories of a beautiful shrine. I carried a deeper understanding of the universality of faith, the ability of a sacred space to transcend geographical and cultural boundaries. While the architecture and rituals may differ, the underlying sentiment, the yearning for connection with the divine, remains the same, whether in the ancient temples of Uttar Pradesh or the vibrant, modern shrine nestled in the Himalayan foothills. The Sankat Mochan Temple, in its own unique way, echoed the spiritual heart of India, a heart that beats strong and true, across diverse landscapes and traditions.

Khongjom Fort Thoubal

The wind carried whispers of resilience as I stood at the foot of Khongjom Fort, a sentinel silhouetted against the Manipuri sky. This wasn't just another fort; it was a scar on the landscape, a testament to a fierce struggle against the British Empire in 1891. Located in Thoubal district, about 36 kilometers from Imphal, Khongjom isn't imposing in size, but its historical weight is immense. It's not a grand, sprawling complex like the forts of Rajasthan I'm accustomed to back home in Gujarat. Instead, it's a series of strategically placed ramparts and trenches, utilizing the natural contours of the hill to maximum defensive advantage. The approach itself sets the tone. A winding road climbs through verdant hills, the air thick with the scent of pine and a palpable sense of history. The fort, or what remains of it, sits atop a small hillock, offering panoramic views of the surrounding valley. The remnants of the mud walls, now overgrown with grass and shrubs, speak volumes about the passage of time and the relentless forces of nature reclaiming its territory. Unlike the intricately carved sandstone and marble of Gujarati architecture, Khongjom’s beauty lies in its stark simplicity and raw power. I walked along the lines of the old trenches, imagining the Manipuri soldiers, armed with swords and spears, holding their ground against the superior firepower of the British. The silence was broken only by the rustling of leaves and the distant chirping of birds, a stark contrast to the cacophony of battle that must have once echoed through these hills. There's a small museum near the fort's entrance, housing relics from the Anglo-Manipuri War. Rusty swords, tattered uniforms, and faded photographs offer a glimpse into the lives of those who fought and fell here. A particular exhibit showcasing traditional Manipuri weaponry – the curved khukri, the spear, and the shield – highlighted the asymmetry of the conflict. The architecture of the fort, while rudimentary, reveals a deep understanding of the terrain. The ramparts, though eroded, still show evidence of strategic placement, designed to maximize visibility and provide cover for the defenders. The use of locally available materials – mud, stone, and timber – speaks to the resourcefulness of the Manipuri people. This contrasts sharply with the elaborate fortifications I've seen in Gujarat, built with intricate carvings and imported materials. Khongjom’s strength lay not in its grandeur, but in its strategic location and the unwavering spirit of its defenders. One structure that stands out is the memorial dedicated to Paona Brajabasi, a Manipuri commander who fought valiantly in the battle. It's a simple, yet powerful structure, built in the traditional Manipuri style with a sloping roof and wooden pillars. The memorial serves as a focal point for remembrance and a symbol of the unwavering spirit of the Manipuri people. Standing there, I could almost feel the weight of history pressing down on me, the echoes of their sacrifice resonating through the air. My visit to Khongjom Fort was more than just a sightseeing trip; it was a pilgrimage. It was a journey into the heart of a story of courage and resilience, a story that deserves to be told and retold. While the fort itself may be in ruins, the spirit of Khongjom remains unbroken, a testament to the enduring power of human resistance against oppression. It offered a poignant contrast to the architectural marvels I'm familiar with back home, reminding me that history is etched not just in stone and marble, but also in the earth itself, in the whispers of the wind, and in the unwavering spirit of a people.

Khair Khana Buddhist Monastery Kabul Afghanistan

Khair Khana, located near Kabul, Afghanistan, preserves the remarkable remains of an 8th century CE Buddhist monastery that represents one of the latest and most sophisticated examples of Buddhist architecture in Afghanistan, demonstrating the persistence of Indian Buddhist traditions in the region even as Buddhism was declining elsewhere, while the discovery of Indic guardian deities and elaborate sculptural programs provides crucial evidence of the continued transmission of Indian artistic and religious traditions to Afghanistan during the late medieval period. The monastery complex, constructed primarily from stone, stucco, and fired brick with extensive decorative elements, features sophisticated architectural design that demonstrates the continued influence of Indian Buddhist monastery architecture, particularly the traditions of northern India, with the overall plan, structural forms, and decorative programs reflecting Indian Buddhist practices that persisted in Afghanistan even as the religion was declining in other regions. The site's architectural design demonstrates direct influence from Indian Buddhist monastery architecture, with the discovery of Indic guardian deities providing particularly important evidence of the transmission of Indian iconographic traditions, while the elaborate sculptural programs demonstrate the sophisticated artistic traditions of the period and the continued influence of Indian artistic styles. Archaeological excavations have revealed extraordinary preservation of sculptures, architectural elements, and artifacts that demonstrate the sophisticated artistic traditions of the 8th century, with the artistic work showing clear influence from Indian styles while incorporating local elements, creating a unique synthesis that characterizes late Buddhist art in Afghanistan. The monastery flourished during the 8th century CE, serving as a major center of Buddhist learning and practice during a period when Buddhism was in decline in many parts of Central Asia, demonstrating the resilience of Buddhist traditions in Afghanistan and the continued transmission of Indian religious and artistic knowledge to the region. The site continued to function as a Buddhist center through the early 9th century CE before gradually declining following the spread of Islam in the region, while the substantial architectural remains that survive provide crucial evidence of the site's original grandeur and the sophisticated engineering techniques employed in its construction. The discovery of Indic guardian deities at the site provides particularly important evidence of the continued transmission of Indian iconographic traditions to Afghanistan during the late medieval period, demonstrating that Indian artistic and religious influences persisted even as Buddhism declined, while the site's location near Kabul underscores its importance as a major religious center in the region. Today, Khair Khana stands as an important archaeological site in Afghanistan, serving as a powerful testament to the country's ancient Buddhist heritage and the persistence of Indian religious and artistic traditions in the region, while ongoing archaeological research and preservation efforts continue to reveal new insights into the site's construction, religious practices, and the late persistence of Buddhism in Afghanistan. ([1][2])

Mandawa Havelis of Jhunjhunu

The desert wind whispered stories as I stepped into Mandawa, a town seemingly frozen in time within the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. It wasn't just a town; it was an open-air art gallery, a canvas of vibrant frescoes splashed across the facades of opulent havelis. My journey through North India has taken me to countless historical sites, but Mandawa's concentration of painted mansions is truly unique. My first stop was the imposing Hanuman Prasad Goenka Haveli. The sheer scale of the structure took my breath away. Intricate carvings adorned every archway and balcony, narrating tales of Rajput chivalry and mythological legends. The colours, though faded by time and the harsh desert sun, still held a captivating vibrancy. I was particularly drawn to a depiction of Krishna lifting Mount Govardhan, the delicate brushstrokes bringing the scene to life despite the passage of centuries. It's evident that the artists weren't merely decorators; they were storytellers, preserving the cultural ethos of a bygone era. Moving on to the Jhunjhunwala Haveli, I was struck by the shift in artistic style. While Hanuman Prasad Goenka Haveli showcased traditional Indian themes, this haveli embraced the advent of the modern world. Frescoes depicting Victorian-era trains and even a biplane shared wall space with traditional motifs. This fascinating juxtaposition highlighted the changing times and the influence of the West on Indian art. It felt like witnessing a dialogue between two worlds, captured in vibrant pigments. The Gulab Rai Ladia Haveli offered another perspective. Here, the frescoes extended beyond mythology and modernity, delving into the everyday life of the merchant families who commissioned these masterpieces. Scenes of bustling marketplaces, elaborate wedding processions, and even depictions of women engaged in household chores provided a glimpse into the social fabric of Mandawa's past. These weren't just grand displays of wealth; they were visual diaries, documenting the nuances of a community. As I wandered through the narrow lanes, each turn revealed another architectural marvel. The intricate latticework screens, known as *jharokhas*, were particularly captivating. They served a dual purpose: allowing the women of the household to observe the street life while maintaining their privacy. These *jharokhas* weren't merely architectural elements; they were symbols of a societal structure, a silent testament to the lives lived within those walls. The double-courtyard layout, a common feature in these havelis, spoke volumes about the importance of family and community. The inner courtyard, often reserved for women, provided a private sanctuary, while the outer courtyard served as a space for social gatherings and business dealings. This architectural division reflected the social dynamics of the time. One aspect that truly resonated with me was the use of natural pigments in the frescoes. The colours, derived from minerals and plants, possessed a unique earthy quality that synthetic paints could never replicate. This connection to nature, so evident in the art, extended to the architecture itself. The thick walls, built from locally sourced sandstone, provided natural insulation against the harsh desert climate, a testament to the ingenuity of the builders. My exploration of Mandawa's havelis wasn't just a visual feast; it was a journey through time. Each brushstroke, each carving, each architectural detail whispered stories of a rich and vibrant past. These havelis aren't just buildings; they are living museums, preserving the cultural heritage of a region. As I left Mandawa, the setting sun casting long shadows across the painted walls, I carried with me not just photographs, but a deeper understanding of the artistry and history that shaped this remarkable town. It's a place I urge every traveller to experience, to lose themselves in the labyrinthine lanes and discover the stories etched onto the walls of these magnificent havelis.

Taip Depe Karakum Desert Turkmenistan

Taip Depe, dramatically rising from the vast expanse of the Karakum Desert in southeastern Turkmenistan, represents one of the most extraordinary and archaeologically significant Bronze Age sites in Central Asia, dating to the 3rd millennium BCE and serving as a major center of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), featuring sophisticated temple structures and ritual complexes that demonstrate remarkable Vedic parallels and connections to ancient Indian religious traditions, creating a powerful testament to the profound transmission of Indian religious and cosmological traditions to Central Asia during the Bronze Age. The site, featuring sophisticated temple structures with central fire altars, ritual chambers, and ceremonial spaces that demonstrate clear parallels with Vedic fire altars and ritual practices described in ancient Indian texts, demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian religious and cosmological concepts from the great religious centers of ancient India, particularly Vedic traditions that were systematically transmitted to Central Asia, while the site's most remarkable feature is its sophisticated temple structures featuring fire altars, ritual complexes, and architectural elements that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Vedic temple architecture and ritual practices. The temple structures' architectural layout, with their central fire altars surrounded by ritual chambers, storage areas, and ceremonial spaces, follows sophisticated planning principles that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Vedic temple planning principles, while the temple structures' extensive decorative programs including ritual objects, seals, and architectural elements demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian religious iconography and cosmological concepts with local Central Asian aesthetic sensibilities. Archaeological evidence reveals that the site served as a major center of religious and ritual activity during the Bronze Age, attracting traders, priests, and elites from across Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East, while the discovery of numerous artifacts including seals with motifs that demonstrate clear Indian influences, ritual objects that parallel Vedic practices, and architectural elements that reflect Indian cosmological concepts provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to Central Asia, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious and cosmological traditions possessed by the site's patrons and religious establishment. The site's association with the BMAC, which had extensive trade and cultural connections with the Indus Valley Civilization and later Indian civilizations, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious traditions that were transmitted to Central Asia, while the site's fire altars and ritual structures demonstrate remarkable parallels with Vedic fire altars and ritual practices that were central to ancient Indian religious traditions. The site has been the subject of extensive archaeological research, with ongoing excavations continuing to reveal new insights into the site's sophisticated architecture, religious practices, and its role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to Central Asia, while the site's status as part of the broader BMAC cultural complex demonstrates its significance as a major center for the transmission of Indian cultural traditions to Central Asia. Today, Taip Depe stands as one of the most important Bronze Age archaeological sites in Central Asia, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian religious and cosmological traditions to Central Asia, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian religious and cultural traditions. ([1][2])

Charaideo Ahom Royal Palace

Nestled amidst the undulating hills of Assam, the Ahom Royal Palace at Charaideo whispers narratives of a kingdom that commanded the region for six centuries ([1]). Unlike the well-documented Mughal and Rajput structures, Charaideo presents a unique and often overlooked chapter of Indian history ([2]). The palace ruins, scattered pavilions, gateways, and protective walls, evoke a profound connection to the surrounding environment ([3]). Stone platforms and foundations demonstrate the architectural ingenuity of the Ahom civilization, dating back to the 13th century ([4]). Fired brick and mud brick construction techniques, combined with locally sourced materials such as bamboo and wood, highlight the Ahom's resourcefulness ([3]). The brickwork features subtle floral motifs, a distinctive characteristic that sets it apart from the geometric patterns prevalent in Islamic architecture ([5]). River stones, seamlessly integrated into the walls, further emphasize the Ahom's deep-rooted connection with the natural landscape ([3]). Archaeological excavations have unveiled the foundations of courtyards and royal pavilions, offering glimpses into the palace's former grandeur and sophisticated planning ([6]). Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, likely influenced the palace's layout, optimizing spatial arrangements in harmony with nature ([7]). Within the complex, sophisticated drainage systems ensured the longevity of the structures, a testament to the Ahom's advanced engineering skills ([8]). The strategic location of Charaideo, providing panoramic vistas of the surrounding landscape, underscores its significance as a vital seat of power ([2]). The Charaideo Ahom Royal Palace stands as a poignant reminder of Assam's rich heritage, meriting greater recognition as a precious jewel of Indian history ([1]).

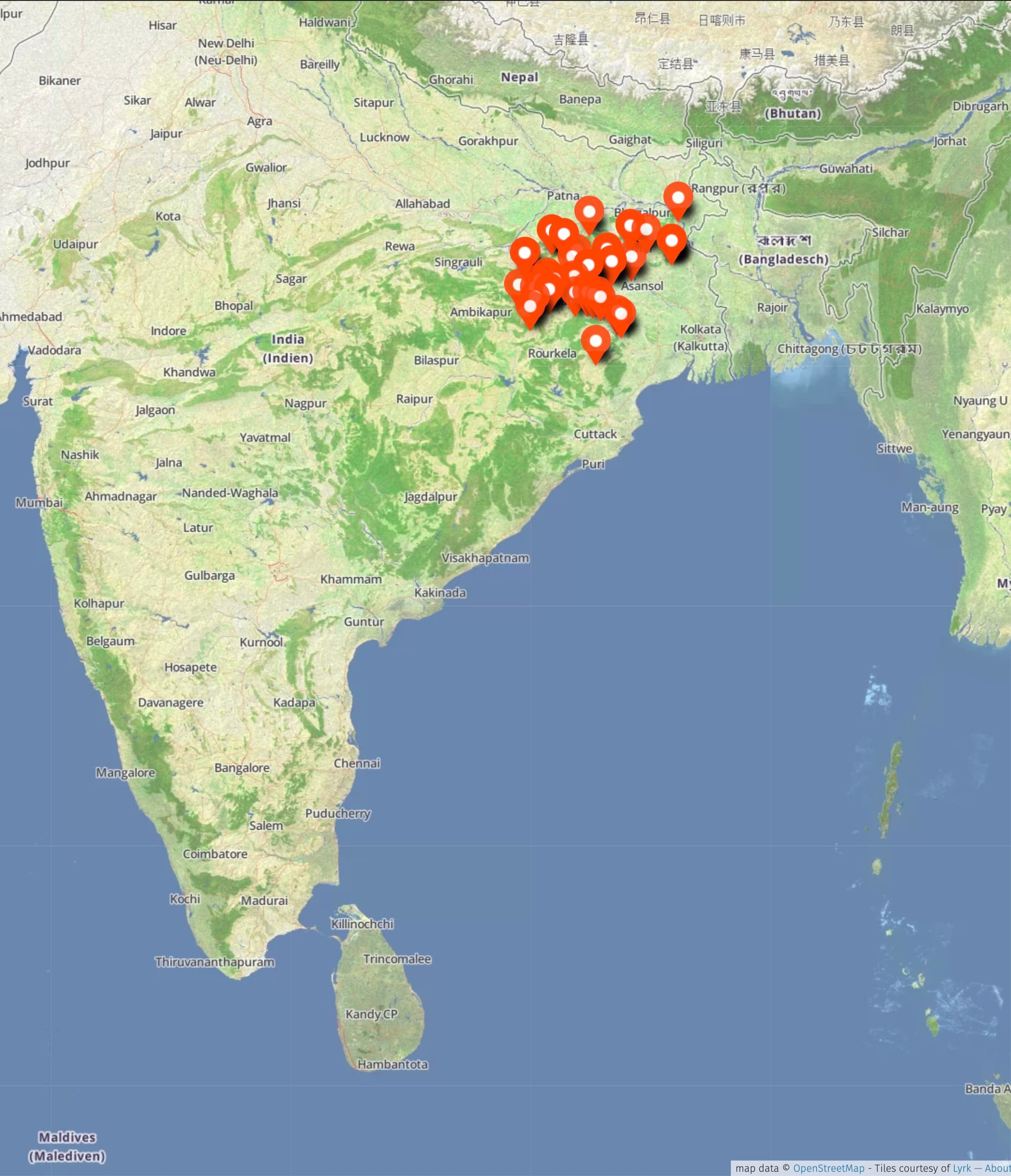

Basukinath Dham Deoghar

Vibrating with spiritual energy, Basukinath Dham in Deoghar, Jharkhand, stands as a testament to India's rich temple-building heritage. Constructed in 1585 CE under the patronage of Raja Puran Mal ([1]), this sacred Shiva temple attracts devotees seeking authentic spiritual connection. Having explored many North Indian temples, Basukinath's architecture exemplifies the Nagara style, characterized by its curvilinear towers and stepped pyramidal structures ([2][3]). Intricate carvings, smoothed by centuries of devotion, adorn the temple's doorway, depicting scenes from Hindu mythology ([4]). The main shrine, dedicated to Lord Shiva, features a modest white structure adorned with prayer flags ([1]). Within the Garbhagriha (Sanctum), a vibrant tapestry of devotees gathers, the air filled with incense and the chanting of "Bol Bam" ([3]). This creates an immersive spiritual experience. Beyond the primary shrine, smaller temples dedicated to various deities enrich the complex ([5]). One such shrine, dedicated to Parvati, showcases remarkably preserved terracotta carvings, reflecting the region's artistic heritage ([5][6]). During the late medieval period, temple architecture flourished under royal patronage, blending regional styles with pan-Indian traditions ([7]). Stone platforms and foundations demonstrate the temple's enduring construction, utilizing locally sourced materials ([8]). The narrow lanes surrounding the temple bustle with stalls selling religious items and local delicacies, adding to the sensory richness of the pilgrimage ([9]). Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, likely guided the temple's layout and orientation, aligning it with cosmic energies ([10]). Basukinath Dham offers a profound connection to India's spiritual and architectural heritage, inviting visitors to experience its unique sanctity.

Sun Temple Bundu

The terracotta hues of the Sun Temple at Bundu, Jharkhand, shimmered under the late afternoon sun, a fitting tribute to the celestial body it honors. Unlike the towering Konark Sun Temple in Odisha, this structure, still under construction, possesses a unique, almost unfinished charm. Its raw, earthy aesthetic, crafted from locally sourced laterite bricks, sets it apart from the polished grandeur of other ancient temples I've encountered across India. This was my 38th UNESCO World Heritage site in India, and it offered a refreshing perspective on temple architecture. The temple's main structure, a colossal chariot seemingly frozen mid-stride, is a marvel of engineering. Seventeen life-sized horses, also sculpted from laterite, appear to pull the chariot, their muscular forms radiating dynamic energy. The wheels, intricately carved with symbolic motifs, are particularly striking. I spent a good amount of time circling the chariot, examining the detailed carvings. While some sections displayed the smooth finish of completed work, others revealed the rough texture of the brick, showcasing the ongoing construction. This juxtaposition of finished and unfinished elements gave the temple a palpable sense of living history. Climbing the steps to the main platform, I was greeted by a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape. The sprawling countryside, dotted with small villages and lush greenery, provided a serene backdrop to the temple's imposing presence. The absence of towering walls or enclosures, typical of many ancient temples, further enhanced this connection with the natural world. It felt as though the temple was not just a place of worship, but an integral part of the landscape itself. Inside the chariot's main chamber, the deity of the Sun God awaits installation. The emptiness of the sanctum, however, did not detract from the spiritual aura of the space. The play of light filtering through the arched openings created an ethereal ambiance, inviting contemplation and quiet reflection. I noticed several artisans working diligently on intricate carvings within the chamber, their meticulous craftsmanship a testament to the dedication involved in bringing this grand vision to life. One of the most captivating aspects of the Bundu Sun Temple is its unique blend of traditional and contemporary architectural styles. While the chariot motif and the use of laterite hark back to ancient temple-building traditions, the sheer scale of the structure and the ongoing construction process give it a distinctly modern feel. It’s a fascinating example of how heritage can be reinterpreted and revitalized for future generations. My conversations with the local artisans and residents provided further insight into the temple's significance. They spoke of the temple not just as a religious site, but as a symbol of community pride and a source of livelihood. The ongoing construction has created employment opportunities for many local artisans, ensuring the preservation of traditional craftsmanship and contributing to the economic development of the region. As I left the Sun Temple, the setting sun cast long shadows across the terracotta structure, painting it in a warm, golden glow. The experience was unlike any other temple visit I’ve had. It wasn’t just about admiring a finished masterpiece; it was about witnessing the creation of one. The Bundu Sun Temple is a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and the evolving nature of heritage. It stands as a powerful reminder that history is not just something we inherit from the past, but something we actively shape in the present.

Namazga-Tepe Ahal Region Turkmenistan

Namazga-Tepe, an ancient Bronze Age settlement located in the Ahal Region of Turkmenistan, stands as a monumental testament to the sophisticated urban planning and cultural dynamism of the Namazga culture, deeply intertwined with the broader cultural continuum that includes the Indian subcontinent [1] [2]. Situated at the foot of the Kopet-Dag mountains, near the delta of the Tejen River, approximately 100 kilometers east of Aşgabat, this archaeological site represents a pivotal center in the ancient world, reflecting indigenous architectural styles and advanced societal organization [1] [3]. The site spans an impressive area of approximately 60 hectares (145 acres), indicating its significant size and importance as a proto-urban and later urban center during its peak phases [1] [2]. The architectural remains at Namazga-Tepe primarily showcase the Bronze Age Settlement architecture style, characterized by extensive mud-brick constructions that formed residential complexes, public buildings, and defensive structures [1] . While specific dimensions of individual structures vary across the site's numerous occupational layers, the overall layout reveals a planned settlement, evolving from a village in the Late Chalcolithic to a major urban hub [1]. Archaeological excavations have unearthed detailed painted pottery vessels, adorned with intricate plant and animal motifs, which exhibit stylistic affinities with contemporary ceramic wares from the Middle East, highlighting extensive regional interactions [2]. The construction techniques employed primarily involved sun-dried mud bricks, a prevalent material in the arid Central Asian environment, demonstrating an indigenous adaptation to local resources and climatic conditions [1]. Conservation efforts at Namazga-Tepe are ongoing, primarily focusing on archaeological excavation, documentation, and site preservation to protect its fragile mud-brick structures from environmental degradation . Archaeological findings have been instrumental in establishing the chronological sequence for the Bronze Age in Turkmenistan, categorizing periods from Namazga I through Namazga VI [1] . The site is reported to be on the UNESCO Tentative List, signifying its recognized universal value and potential for future World Heritage inscription, although a specific UNESCO page detailing its nomination is not readily available . Active programming at the site primarily involves scholarly research and archaeological fieldwork, with visitor access managed to ensure the preservation of the delicate ancient remains. The site's current state reflects continuous archaeological investigation and maintenance, ensuring its long-term preservation for future study and appreciation of its profound historical significance . Namazga-Tepe remains an enduring symbol of ancient ingenuity and cultural exchange, contributing significantly to the understanding of early urbanism and its connections across Eurasia, including the Indian subcontinent [3] [4].

Sharada Peeth Ruins Sharda

The wind carried whispers of forgotten chants as I stood before the Sharada Peeth ruins, a skeletal monument against the dramatic backdrop of the Neelum Valley. Located near the Line of Control, this ancient seat of learning, once revered across the subcontinent, now stands as a poignant testament to time's relentless march. My journey here, through the rugged terrain of Kashmir, felt like a pilgrimage, each step imbued with anticipation. The first glimpse of the ruins, perched on a plateau overlooking the Kishanganga River (also known as the Neelum River in this region), was breathtaking. The sheer scale of the site, even in its dilapidated state, hinted at its former grandeur. The remaining stonework, primarily constructed from local grey and white stone, displayed intricate carvings, weathered yet still legible. Floral motifs, geometric patterns, and depictions of deities intertwined, narrating stories of a rich artistic heritage. The architecture, a blend of Kashmiri and Gandharan styles, was evident in the pointed arches, the remnants of pillared halls, and the distinctive pyramidal roof structure, now sadly collapsed. I walked through the ruins, tracing the outlines of what were once classrooms, libraries, and assembly halls. Imagining the vibrant intellectual life that once thrived here, the murmur of scholars debating philosophy and scriptures, was both exhilarating and melancholic. The central shrine, dedicated to the goddess of learning, Sharada, was particularly moving. Although the idol was missing, the sanctity of the space remained palpable. The smooth, worn stones of the sanctum sanctorum seemed to hold the echoes of countless prayers and devotions. One of the most striking features of the site was the abundance of inscriptions. Scattered across the walls and pillars, these inscriptions, in various scripts including Sharada, Devanagari, and Persian, offered a glimpse into the site's diverse history. They spoke of royal patronage, scholarly achievements, and the pilgrimage traditions that drew people from far and wide. I spent hours deciphering the visible portions, feeling a tangible connection to the generations who had walked these very paths centuries before. Looking across the valley, I noticed the remnants of a network of ancient trails, now overgrown and barely discernible. These trails, I learned, were once the arteries of knowledge, connecting Sharada Peeth to other major learning centers across the region. The site wasn't just a temple or a university; it was a hub of cultural exchange, a melting pot of ideas and philosophies. The current state of the ruins, however, is a stark reminder of the fragility of heritage. The ravages of time, coupled with the impact of natural disasters and political instability, have taken their toll. Many sections have collapsed, and the remaining structures are in dire need of conservation. While some local efforts are underway, a more comprehensive and sustained approach is crucial to preserve this invaluable piece of history. Leaving Sharada Peeth was bittersweet. The journey had been physically demanding, but the experience was profoundly enriching. It was more than just visiting an archaeological site; it was a journey through time, a communion with the past. The whispers of forgotten chants seemed to follow me as I descended the mountain, a constant reminder of the knowledge lost and the urgent need to protect what remains. Sharada Peeth stands not just as a ruin, but as a symbol of resilience, a testament to the enduring power of human intellect and the enduring quest for knowledge. It is a site that deserves not just our attention, but our active commitment to its preservation, ensuring that the whispers of the past don't fade into silence.

Maner Palace Maner Patna

The Ganges flowed serenely beside me, a silent witness to centuries of history as I approached Maner Palace, a structure seemingly woven from the very fabric of time. Located in Maner, a small town a short distance from Patna, the palace stands as a poignant reminder of Bihar's rich and layered past, a confluence of Mughal and Rajput architectural styles. The crumbling ochre walls, kissed by the sun and etched with the passage of time, whispered stories of emperors, queens, and the ebb and flow of power. My camera, an extension of my own inquisitive gaze, immediately sought out the intricate details. The palace, though in a state of disrepair, still exuded a regal aura. The arched gateways, reminiscent of Mughal design, framed glimpses of inner courtyards, now overgrown with tenacious weeds that seemed to be reclaiming the space. The Rajput influence was evident in the chhatris, those elegant, domed pavilions that crowned the roofline, offering panoramic views of the river and the surrounding landscape. I imagined the royalty of bygone eras enjoying the same vista, perhaps contemplating the vastness of their empire. Stepping inside the main structure, I was struck by the stark contrast between the grandeur of the past and the decay of the present. Elaborate carvings, once vibrant with colour, now bore the muted hues of age and neglect. Floral motifs intertwined with geometric patterns, a testament to the skilled artisans who had painstakingly created these masterpieces. I ran my fingers along the cool stone walls, tracing the outlines of these forgotten stories. The air hung heavy with the scent of damp earth and the faint whisper of the river, creating an atmosphere both melancholic and strangely serene. One of the most captivating aspects of Maner Palace is its connection to the legendary Sher Shah Suri. The remnants of his mosque, a testament to his brief but impactful reign, stand within the palace complex. The mosque's simple yet elegant design, characterized by its imposing dome and slender minarets, spoke of a pragmatic ruler who valued functionality as much as aesthetics. I spent a considerable amount of time photographing the interplay of light and shadow on the mosque's weathered facade, trying to capture the essence of its historical significance. Climbing the narrow, winding staircase to the upper levels of the palace, I was rewarded with breathtaking views of the Ganges. The river, a lifeline for countless generations, shimmered under the midday sun. From this vantage point, I could appreciate the strategic importance of Maner, a town that had witnessed the rise and fall of empires. The wind carried with it the distant sounds of life from the town below, a stark reminder that history continues to unfold, even amidst the ruins of the past. My lens focused on the intricate jali work, the delicate lattice screens that once offered privacy to the palace's inhabitants. The patterns, intricate and varied, were a testament to the artistry of the period. I imagined the women of the court peering through these screens, observing the world outside while remaining unseen. The jali work, now fragmented and weathered, served as a poignant metaphor for the fragility of time and the ephemeral nature of power. Leaving Maner Palace, I carried with me a profound sense of awe and a renewed appreciation for the rich tapestry of Indian history. The palace, though in ruins, is not merely a collection of crumbling walls and faded frescoes. It is a living testament to the human spirit, a reminder of the enduring power of art, architecture, and the stories they tell. My photographs, I hope, will serve as a window into this forgotten world, inspiring others to explore the hidden gems of our heritage and to appreciate the beauty that lies within decay.

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides