Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

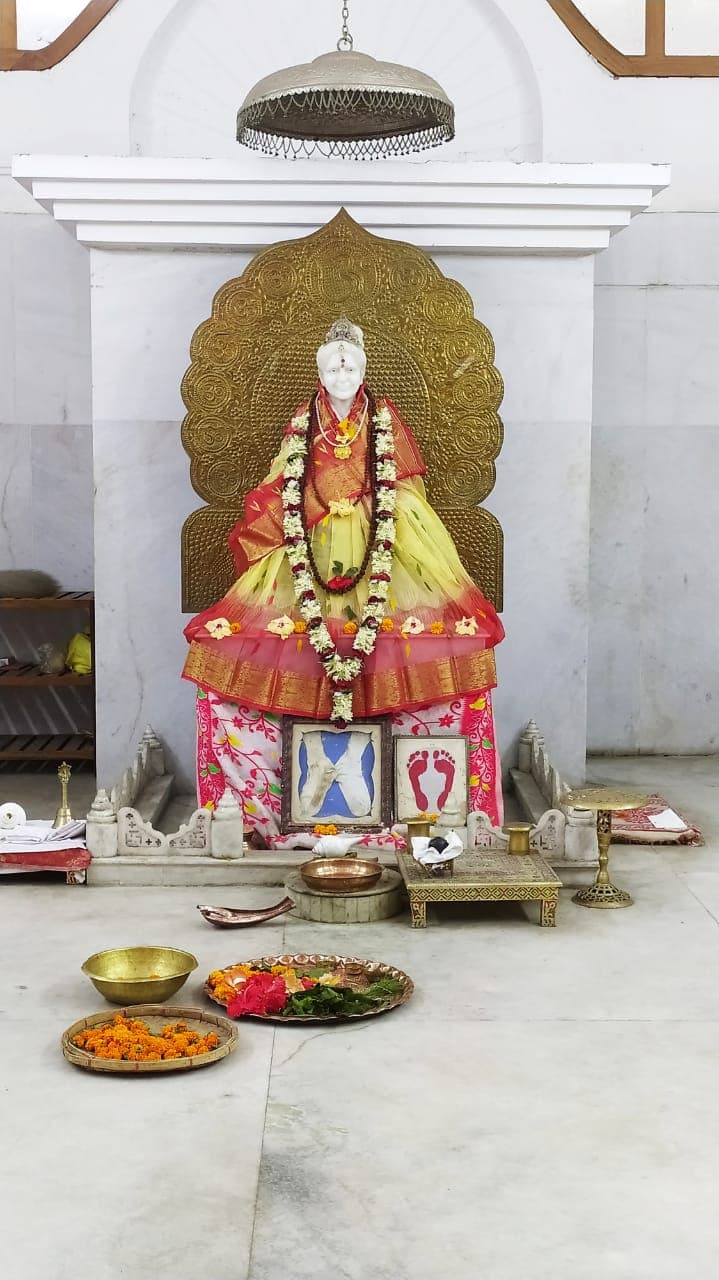

Shiv-Parvati Mandir Hnahthial

The air hung thick and humid, a stark contrast to the arid landscapes of Rajasthan I’m accustomed to. Here in Hnahthial, Mizoram, nestled amidst verdant hills, the Shiv-Parvati Mandir stands as a testament to the surprising religious diversity of this northeastern state. The temple, a relatively recent construction compared to the ancient forts and palaces I’ve explored back home, possesses a unique charm, blending traditional North Indian temple architecture with local Mizo influences. The first thing that struck me was the vibrant colours. Unlike the sandstone hues of Rajasthan’s temples, this one is painted in bright shades of orange, yellow, and red, creating a cheerful, almost festive atmosphere. The main structure rises in a series of tiered roofs, reminiscent of a classic Nagara style shikhara, yet the curvature is gentler, less pronounced. Instead of intricate carvings, the exterior walls are adorned with simpler, bolder motifs – geometric patterns and stylized floral designs that hint at Mizo artistic traditions. Ascending the steps to the main entrance, I noticed the absence of the elaborate gateways and towering gopurams common in South Indian temples. The entrance is relatively modest, framed by two pillars decorated with colourful depictions of deities. Stepping inside, I was greeted by the cool, dimly lit interior. The main sanctum houses the idols of Shiva and Parvati, adorned with vibrant clothing and garlands. The atmosphere was serene, filled with the murmur of prayers and the scent of incense. What truly captivated me was the seamless integration of local elements within the predominantly North Indian architectural framework. The use of locally sourced materials, like bamboo and wood, in the construction of the ancillary structures surrounding the main temple, is a clear example. I observed a small pavilion, crafted entirely from bamboo, serving as a resting place for devotees. The intricate weaving patterns on the bamboo walls showcased the remarkable craftsmanship of the local artisans. The temple complex also houses a small garden, a welcome splash of green amidst the concrete structures. Unlike the meticulously manicured gardens of Rajasthan’s palaces, this one felt more natural, with flowering plants and fruit trees growing in abundance. The gentle rustling of leaves in the breeze added to the tranquil atmosphere. Interacting with the local priest, I learned about the history of the temple. It was fascinating to hear how the local community, predominantly Christian, embraced the construction of this Hindu temple, reflecting the spirit of religious tolerance that permeates Mizoram. He explained how the temple serves as a focal point not just for religious ceremonies but also for social gatherings and cultural events, further strengthening the bonds within the community. As I walked around the temple complex, observing the devotees offering prayers, I couldn't help but draw parallels between the religious practices here and those back home. Despite the geographical distance and cultural differences, the underlying devotion and reverence remained the same. The ringing of bells, the chanting of mantras, the offering of flowers – these rituals transcended regional boundaries, reminding me of the unifying power of faith. Leaving the Shiv-Parvati Mandir, I carried with me a sense of quiet admiration. This temple, a unique blend of architectural styles and cultural influences, stands as a symbol of harmony and acceptance. It’s a testament to the fact that even in the most unexpected corners of India, one can find expressions of faith that resonate deeply with the human spirit. It’s a far cry from the majestic forts and palaces of Rajasthan, yet it holds its own unique charm, offering a glimpse into the rich tapestry of India’s cultural and religious landscape.

Gorkha Durga Temple Shillong

The crisp Shillong air, tinged with the scent of pine, carried a faint echo of drums as I approached the Gorkha Durga Temple. Nestled amidst the undulating hills, the temple, painted a vibrant shade of saffron, presented a striking contrast against the verdant backdrop. It wasn't the towering grandeur of some of the ancient temples I've documented that captivated me, but rather its unique blend of Nepali and indigenous Khasi influences, a testament to the cultural confluence of this region. The temple's two-tiered structure, reminiscent of traditional Nepali pagoda architecture, immediately caught my eye. The sloping roofs, adorned with intricate wooden carvings, cascaded downwards, culminating in ornate finials. Unlike the elaborate stonework I'm accustomed to seeing in temples across India, here, wood was the primary medium. The richly carved panels depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, particularly those of Durga in her various forms, showcased a distinct artistic style. The figures, though stylized, possessed a dynamic energy, their expressions vividly conveying stories of power and devotion. As I ascended the steps leading to the main sanctum, I noticed the subtle integration of Khasi elements. The use of locally sourced stone for the foundation and the steps, and the incorporation of motifs inspired by Khasi traditional patterns into the woodwork, spoke volumes about the cultural exchange that shaped this sacred space. It wasn't merely a transplantation of Nepali architecture but a conscious adaptation, a harmonious blending of two distinct artistic traditions. Inside the sanctum, the atmosphere was charged with a palpable sense of reverence. The deity, Durga, was represented in her Mahishasuramardini avatar, the slayer of the buffalo demon. The idol, though smaller than those found in grander temples, radiated an aura of strength and tranquility. The rhythmic chanting of mantras by the priest, punctuated by the clang of bells, created an immersive spiritual experience. What struck me most was the temple's intimate scale. Unlike the sprawling complexes I've encountered elsewhere, the Gorkha Durga Temple felt personal, almost like a community shrine. The courtyard, though modest in size, was meticulously maintained, with colourful prayer flags fluttering in the breeze, adding a touch of vibrancy to the serene setting. I observed devotees, both Nepali and Khasi, offering prayers, their faces reflecting a shared sense of devotion, a testament to the unifying power of faith. The temple's location itself added another layer of significance. Perched atop a hill, it offered panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. The rolling hills, dotted with pine trees, stretched out as far as the eye could see, creating a sense of tranquility and connection with nature. It was easy to see why this spot was chosen as a sacred site. The natural beauty of the surroundings seemed to amplify the spiritual energy of the temple, creating a space where the earthly and the divine converged. My visit to the Gorkha Durga Temple was more than just an architectural exploration; it was a cultural immersion. It offered a glimpse into the complex tapestry of traditions that make up the social fabric of Meghalaya. The temple stands as a powerful symbol of cultural exchange, a testament to the ability of different communities to not only coexist but to create something beautiful and unique through their interactions. It is a reminder that architecture can be more than just bricks and mortar; it can be a living embodiment of shared history, faith, and artistic expression.

Brisbane Sri Selva Vinayakar Koil South Maclean

Anchoring Logan’s peri-urban corridor, Brisbane Sri Selva Vinayakar Koil South Maclean stands as Queensland’s first traditional Hindu temple dedicated to Lord Ganesha ([1][2]). Established around 1990 CE, this 20th-century temple reflects Dravidian architectural influences adapted to a rural Australian context ([1]). The temple was built by the Hindu Society of Queensland, who also continue to be its patron ([1]). Granite and sandstone blocks, meticulously carved, form the core of the Mandapa (Pillared Hall), while timber posts and corrugated steel roofing provide a functional and aesthetically pleasing structure ([1]). Daily rituals, or darshan, are conducted between 6:30 AM and 12:00 PM, and again from 4:30 PM to 8:30 PM ([1][5]). Special occasions such as Vinayagar Chaturthi, Thai Poosam, and Navaratri extend these hours until 10:00 PM ([1][5]). To manage the flow of devotees, volunteers guide visitors through the granite Mandapa using rope-guided lanes, ensuring a smooth and organized experience ([1][5]). Shuttle buggies are also available to assist elders in navigating the expansive site ([1][5]). Within the annadhanam shed, which can accommodate 300 people, polished concrete floors provide a clean and functional space for communal dining ([1][3]). Modern amenities such as induction woks and commercial chillers support the preparation and storage of prasadam (sacred food), with HACCP checklists ensuring food safety standards are maintained ([1][3]). Portable ramps facilitate the movement of prasadam carts between the kitchen and hall, even during inclement weather ([1][3]). Beyond worship, the temple serves as a cultural hub, hosting dance, music, and language classes in its cultural pavilion ([2]). A meditation pond and vahana sheds are situated along the Logan River flood fringe, with boardwalks and warning signage in place ([2]). Accessibility is a priority, with gravel-stabilized pathways, handrails, tactile signage, and a platform lift near the sanctum ensuring inclusivity ([2][5]). Auslan interpreters are also available during major festivals ([2][5]). Sophisticated drainage systems ensure the temple grounds remain functional, even during heavy rainfall ([3]). Digital signage displays bilingual Tamil-English instructions, weather alerts, and seva schedules, keeping the community informed and engaged ([1][2]). The temple's operations team monitors weather stations, flood gauges, and fire equipment, while the Logan Rural Fire Brigade conducts annual drills on site, ensuring preparedness for any eventuality ([3]). This proactive approach underscores the temple's commitment to community resilience and safety ([1][2]).

Khalchayan Temple Ruins Lebap Turkmenistan

Khalchayan Temple Ruins, dramatically situated in the Lebap Region of eastern Turkmenistan, represents one of the most extraordinary and archaeologically significant Kushan-period sites in Central Asia, dating to the 2nd century BCE and featuring remarkable Indic sculptures and architectural elements that demonstrate the profound transmission of Indian Buddhist and Hindu religious and artistic traditions to Central Asia during the Kushan period, creating a powerful testament to the sophisticated synthesis of Indian and Central Asian cultural traditions. The temple ruins, featuring sophisticated architectural elements and extraordinary Indic sculptures executed in the distinctive Kushan-Gandharan style that emerged from the synthesis of Indian and Central Asian artistic traditions, demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian Buddhist and Hindu iconographic programs and artistic traditions from the great artistic centers of India including Gandhara, Mathura, and the monastic centers of northern India, while the site's most remarkable feature is its extraordinary collection of Indic sculptures featuring Buddha images, Bodhisattvas, and Hindu deities executed with remarkable artistic sophistication and iconographic accuracy that demonstrate the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist and Hindu iconography possessed by Kushan artists. The temple ruins' architectural layout, with their central structures surrounded by ritual spaces and architectural elements, follows sophisticated planning principles that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian Buddhist and Hindu temple planning principles, while the temple ruins' extensive decorative programs including Indic sculptures, architectural elements, and religious iconography demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Buddhist and Hindu iconography and artistic traditions with local Central Asian aesthetic sensibilities, particularly the distinctive Kushan-Gandharan style that emerged from the synthesis of Indian and Central Asian artistic traditions. Archaeological evidence reveals that the site served as a major center of religious and artistic activity during the Kushan period, attracting traders, artists, and religious practitioners from across Central Asia, South Asia, and beyond, while the discovery of numerous Indic sculptures including Buddha images, Bodhisattvas, and Hindu deities that demonstrate clear Indian influences, architectural elements that parallel Indian practices, and religious iconography that reflects Indian Buddhist and Hindu cosmological concepts provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian religious and artistic traditions to Central Asia, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist and Hindu traditions possessed by the site's patrons and artistic establishment. The site's association with the Kushan Empire, which had strong connections to India and played a crucial role in the transmission of Indian religious and artistic traditions to Central Asia, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious and artistic traditions that were transmitted to Central Asia, while the site's Indic sculptures and architectural elements demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian Buddhist and Hindu temple architecture and iconographic programs that were central to ancient Indian religious traditions. The site has been the subject of extensive archaeological research, with ongoing excavations continuing to reveal new insights into the site's sophisticated architecture, artistic programs, and its role in the transmission of Indian religious and artistic traditions to Central Asia, while the site's status as a UNESCO Tentative List site demonstrates its significance as a major center for the transmission of Indian cultural traditions to Central Asia. Today, Khalchayan Temple Ruins stands as a UNESCO Tentative List site and represents one of the most important Kushan-period sites in Central Asia, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Buddhist and Hindu culture and art to Central Asia, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian religious and artistic traditions. ([1][2])

Gorsam Chorten Bomdila

Gorsam Chorten, a revered Indo-Tibetan Buddhist stupa, stands as a profound testament to India's millennia-spanning cultural heritage in Cona, West Kameng, Bomdila, Arunachal Pradesh. This monumental structure, deeply rooted in the continuous tradition of Indian civilization, embodies indigenous architectural styles and cultural practices that reflect the region's deep historical connections. The chorten, a large white stupa, features a massive hemispherical dome resting upon a three-tiered square base, culminating in a pyramidal spire adorned with the 'all-seeing eyes' of the Buddha, a design reminiscent of the Boudhanath Stupa in Kathmandu. Four miniature stupas are strategically erected at the corners of the plinth, enhancing its sacred geometry. The structure reaches an approximate height of 28.28 meters, with a width of 10.2 meters and a length of 21.64 meters, encompassing an area of 161.874 square meters. Its construction primarily utilizes locally sourced materials such as stone, wood, and clay, bound together with mud mortar, showcasing traditional Monpa craftsmanship and dry stone masonry techniques. This method, adapted to the Himalayan environment, involves meticulously layered stones fitted with precision to minimize voids and maximize interlocking, providing inherent flexibility against seismic activity. The mud mortar, likely incorporating local clay and natural fibers, enhances stability and weather resistance. The exterior is whitewashed, with golden embellishments and a golden finial that gleams in the sunlight. Around the base, a series of prayer wheels, painted in vibrant hues of red, blue, and gold, invite circumambulation. The interior of the chorten houses a dimly lit chamber containing several statues of Buddha, radiating profound peace. The walls are adorned with intricate murals depicting scenes from the Buddha's life, showcasing a unique regional artistic style with bolder lines and intense colors. Recurring motifs of the eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism—the parasol, golden fish, treasure vase, lotus flower, conch shell, endless knot, victory banner, and Dharma wheel—are intricately woven into the murals and carved into the woodwork. The site is well-maintained, with ongoing conservation efforts focusing on structural repairs, mending cracks in masonry, and repainting surfaces, often employing traditional techniques to preserve its historical and religious integrity. Archaeological excavations have revealed a hidden chamber beneath the stupa, unearthing relics such as miniature clay stupas, a bronze image of Vajrasattva, and ancient scriptures, confirming its significance as a major Buddhist pilgrimage site. The Gorsam Chorten remains an active spiritual sanctuary, drawing thousands of pilgrims, particularly during the annual Gorsam Kora festival. It is accessible to visitors from sunrise to sunset daily, with free entry, though accessibility for wheelchairs is limited due to hilly terrain and steps. Modest dress is required, and photography may be restricted in certain areas to maintain the sanctity of the active monastery. The site is operationally ready, serving as a living embodiment of faith and tradition within India's enduring cultural legacy.

Huynh De Citadel Cham Temples Binh Dinh Vietnam

The Huynh De Citadel Cham Temples, situated in Binh Dinh Province, Vietnam, represent a profound testament to India's millennia-spanning cultural heritage, embodying the continuous tradition of Indian civilization through its architectural and religious expressions. This monumental complex, also known historically as Hoàng Đế Citadel or Cha Ban Citadel, served as a significant political and religious center for the Champa Kingdom, deeply influenced by ancient Indian architectural principles and spiritual practices [2] . The indigenous Cham architectural style, particularly evident in the temple structures, exhibits striking similarities to the Dravida architecture style and Hindu temple architecture of South India, reflecting a direct cultural transmission and adaptation [1] [5]. The temples within the citadel area are predominantly dedicated to Hindu deities, with Shiva, often manifested as the Bhadreśvara-liṅga or in anthropomorphic form, being the primary object of worship [1]. Decorative elements frequently include depictions of Hindu goddesses such as Gajalakshmi, carved on tympanums, and figures like the brick Garuda on temple roofs, underscoring the pervasive Hindu iconography [1]. The construction primarily utilizes red brick, a characteristic material for Cham temples, complemented by sandstone for structural elements and intricate carvings [1] . Early construction phases, dating from the 7th to 9th centuries, featured smaller temples with low brick walls and wooden pillars supporting tiled roofs, creating an 'open-sanctum' design that allowed natural light to permeate the interior [1]. By the late 9th to 13th centuries, construction techniques advanced, leading to taller temple towers built with corbelling techniques and pointed roofs, resulting in 'closed-sanctum' structures illuminated by internal light sources like candles or torches [1]. Specific architectural marvels include the Duong Long Towers, a triple-tower complex from the 12th century, where the central tower reaches an impressive height of 39 meters, flanked by two slightly shorter structures [2]. The Banh It towers, dating from the 12th to 13th centuries, comprise four meticulously restored towers strategically positioned atop a hill, offering panoramic views [2]. The Canh Tien Tower, a 12th-century edifice within the Vijaya Citadel, showcases elaborate decorative features inspired by tropical foliage, a hallmark of Cham artistry [2] . The Phu Loc tower, an early 12th-century structure, stands as a colossal, castle-like edifice, while the Thap Doi (Twin Towers) from the 12th-13th century rise 20 meters, tapering upwards like monumental chimneys [2]. The Binh Lam tower, from the late 10th to early 11th century, is a solitary, large structure notable for its street-level placement [2]. The Huynh De Citadel itself functioned as a formidable defensive complex, characterized by its rectangular layout and extensive ramparts. Historical records detail the southern rampart, constructed from large laterite blocks, each measuring approximately 0.8 meters in length, 0.4 meters in width, and 0.23 meters in thickness, with roof tile fragments inserted for enhanced stability . The citadel was ingeniously integrated with its natural environment, surrounded by a network of deep and wide moats connected to local rivers and lagoons, providing both strategic defense and efficient water management . Archaeological excavations continue to reveal foundational layers, pottery, and other artifacts, shedding light on the site's continuous occupation and evolution [4] . The site is currently designated as a protected historical area, with ongoing conservation efforts focused on preserving its ancient structures and uncovering further archaeological insights, ensuring its operational readiness for scholarly research and public appreciation of India's enduring cultural legacy [4] .

Uma Maheshwari Temple Agartala

The midday sun cast long shadows across the courtyard of the Uma Maheshwari Temple in Agartala, dappling the red brick façade with an intricate play of light and shade. As a cultural journalist from Uttar Pradesh, steeped in the architectural narratives of the Gangetic plains, I found myself captivated by this unexpected burst of North Indian temple architecture nestled within the heart of Tripura. The temple, dedicated to Uma Maheshwari, a combined form of Parvati and Shiva, stands as a testament to the cultural exchange and historical connections that have shaped this northeastern state. The first thing that struck me was the temple's relatively modest scale compared to the sprawling complexes I'm accustomed to back home. Yet, within this compact footprint, the architects have managed to capture the essence of Nagara style architecture. The shikhara, the curvilinear tower rising above the sanctum sanctorum, is the defining feature. While smaller than the towering shikharas of, say, the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple in Khajuraho, it retains the same graceful upward sweep, culminating in a pointed amalaka. The brick construction, however, sets it apart from the sandstone temples of North India, lending it a distinct regional flavour. Close inspection revealed intricate terracotta work adorning the shikhara, depicting floral motifs and divine figures, a craft that echoes the rich terracotta traditions of Bengal. Stepping inside the garbhagriha, the sanctum sanctorum, I was met with a palpable sense of serenity. The deities, Uma and Maheshwar, are enshrined here in a simple yet elegant manner. Unlike the elaborate iconography found in some North Indian temples, the focus here seemed to be on the spiritual essence of the deities, fostering a sense of quiet contemplation. The priest, noticing my interest, explained that the temple was constructed in the 16th century by the Manikya dynasty, rulers of the Tripura Kingdom, who traced their lineage back to the Lunar dynasty of mythology, further strengthening the connection to North Indian traditions. The temple courtyard, enclosed by a low wall, offers a peaceful respite from the bustling city outside. Several smaller shrines dedicated to other deities dot the perimeter, creating a microcosm of the Hindu pantheon. I spent some time observing the devotees, a mix of locals and visitors, engaging in their prayers and rituals. The air was thick with the fragrance of incense and the murmur of chants, creating an atmosphere of devotion that transcended regional boundaries. What intrigued me most was the seamless blending of architectural styles. While the core structure adhered to the Nagara style, elements of Bengali temple architecture were subtly interwoven. The use of brick, the terracotta ornamentation, and the chala-style roof over the mandapa, or assembly hall, all pointed towards a conscious assimilation of local architectural idioms. This architectural hybridity, I realized, mirrored the cultural synthesis that has shaped Tripura's identity over centuries. As I left the Uma Maheshwari Temple, I carried with me not just the visual memory of its elegant form but also a deeper understanding of the complex cultural tapestry of India. The temple stands as a powerful symbol of how cultural influences can traverse geographical boundaries, intermingle, and create something unique and beautiful. It serves as a reminder that while regional variations enrich our heritage, the underlying spiritual and artistic threads that bind us together are far stronger than the differences that might appear to separate us. It is in these spaces, where architectural styles converge and cultural narratives intertwine, that we truly grasp the richness and diversity of the Indian civilization.

Surya Mandir Deo

The sun beat down on the parched landscape of Aurangabad district, Bihar, but the real heat, the real energy, emanated from the Surya Mandir in Deo. Having crisscrossed North India, explored countless temples from the Himalayas to the plains, I thought I’d seen it all. I was wrong. The Surya Mandir, a relatively unsung hero of Indian architecture, struck me with a force I hadn't anticipated. It wasn't just a temple; it was a statement, a testament to a bygone era’s devotion and artistry. The temple, dedicated to the sun god Surya, stands as a solitary sentinel amidst fields of swaying crops. Its imposing structure, crafted from red sandstone, rises in three receding tiers, each intricately carved with a narrative that unfolds like a visual epic. The first tier, closest to the earth, is a riot of life. Elephants, horses, celestial beings, and scenes from daily life are etched into the stone, a vibrant tableau of the earthly realm. I ran my hand over the weathered surface, tracing the lines of a particularly spirited elephant, marveling at the skill of the artisans who breathed life into these stones centuries ago. Ascending the worn steps to the second tier, the narrative shifts. The carvings become more celestial, depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, gods and goddesses locked in eternal dance, their stories whispered by the wind that whistled through the crumbling archways. Here, the earthly exuberance gives way to a more refined, spiritual energy. I noticed the intricate latticework screens, jalis, that allowed slivers of sunlight to penetrate the inner sanctum, creating an ethereal play of light and shadow. The third and highest tier, sadly damaged by the ravages of time and neglect, still holds a palpable sense of grandeur. It is here, I imagined, that the priests would have performed their rituals, bathed in the first rays of the rising sun. The panoramic view from this vantage point was breathtaking. The flat expanse of Bihar stretched out before me, the temple a solitary beacon of faith amidst the mundane. The architecture is a unique blend of various North Indian styles, showcasing influences from the Pala and Gurjara-Pratihara periods. The shikhara, the towering spire that typically crowns North Indian temples, is absent here, replaced by a flattened pyramidal roof, a feature that intrigued me. It lent the temple a distinct silhouette, setting it apart from the more conventional Nagara style temples I’d encountered elsewhere. What struck me most, however, wasn't just the architectural brilliance but the palpable sense of history that permeated every stone. Unlike the bustling, tourist-laden temples I’d visited in Varanasi or Khajuraho, the Surya Mandir in Deo felt forgotten, almost abandoned. This solitude, however, amplified its power. I could almost hear the echoes of ancient chants, feel the presence of the devotees who once thronged these courtyards. The neglect, though disheartening, added another layer to the temple's story. Broken sculptures, crumbling walls, and overgrown vegetation spoke of a glorious past and a precarious present. It underscored the urgent need for preservation, for safeguarding these invaluable fragments of our heritage. As I descended the steps, leaving the temple behind, I felt a pang of sadness, but also a sense of hope. The Surya Mandir in Deo, though overshadowed by its more famous counterparts, holds a unique charm, a quiet dignity that resonates deeply. It is a place that deserves to be rediscovered, a testament to the enduring power of faith and the artistry of a forgotten era. It is a place that will stay etched in my memory, a hidden gem in the heart of Bihar.

Hutheesing Jain Temple Ahmedabad

The midday sun cast long shadows across the courtyard, dappling the intricately carved marble of the Hutheesing Jain Temple. Stepping through the ornate torana, I felt a palpable shift, a sense of entering a sacred space meticulously crafted for contemplation and reverence. Located in the heart of bustling Ahmedabad, this 19th-century marvel stands as a testament to the enduring artistry of Jain craftsmanship and the devotion of its patrons. My lens, accustomed to the sandstone hues of Madhya Pradesh's ancient monuments, was immediately captivated by the sheer whiteness of the marble. It glowed, almost ethereal, against the azure sky. The main temple, dedicated to Dharmanatha, the fifteenth Jain Tirthankara, is a symphony in stone. Fifty-two intricately carved shrines, each housing a Tirthankara image, surround the central sanctum. The sheer density of the carvings is breathtaking. Floral motifs, celestial beings, and intricate geometric patterns intertwine, creating a visual tapestry that demands close inspection. I spent hours moving from shrine to shrine, my camera attempting to capture the nuances of each individual sculpture, the delicate expressions on the faces of the deities, the flow of the drapery, the minute details that spoke volumes about the skill of the artisans. The temple’s architecture follows the Māru-Gurjara style, a distinctive blend of architectural elements that I found particularly fascinating. The domed ceilings, the ornate pillars, the intricate brackets supporting the balconies – each element contributed to a sense of grandeur and harmony. The play of light and shadow within the temple added another layer of visual interest. As the sun shifted, the carvings seemed to come alive, revealing new details and textures. I found myself constantly repositioning, seeking the perfect angle to capture the interplay of light and form. Beyond the main temple, the courtyard itself is a marvel. The paved floor, polished smooth by centuries of footsteps, reflects the surrounding structures, creating a sense of spaciousness. Smaller shrines and pavilions dot the courtyard, each a miniature masterpiece of carving and design. I was particularly drawn to the Manastambha, a freestanding pillar adorned with intricate carvings, standing tall in the center of the courtyard. It served as a powerful visual reminder of the Jain principles of non-violence and universal compassion. One aspect that struck me was the palpable sense of peace that permeated the temple complex. Despite its location in a busy city, the Hutheesing Jain Temple felt like an oasis of tranquility. The hushed whispers of devotees, the gentle clinking of bells, the rhythmic chanting of prayers – all contributed to an atmosphere of serenity and reverence. It was a stark contrast to the cacophony of the streets outside. As a heritage photographer, I’ve visited countless temples across India, but the Hutheesing Jain Temple holds a special place in my memory. It’s not just the architectural brilliance or the sheer artistry of the carvings, but the palpable sense of devotion and the peaceful atmosphere that truly sets it apart. It’s a place where spirituality and art intertwine, creating an experience that is both visually stunning and deeply moving. My photographs, I hope, will serve as a testament to the enduring beauty and spiritual significance of this remarkable temple, allowing others to glimpse the magic I witnessed within its marble walls.

Sarveshwar Mahadev Temple Kurukshetra

The late afternoon sun cast long shadows across the Kurukshetra battlefield, imbuing the landscape with a palpable sense of history. But it wasn't the echoes of ancient warfare that drew me here; it was the Sarveshwar Mahadev Temple, a structure whispering tales of devotion amidst the whispers of war. Standing before its weathered facade, I felt a tug, a connection to layers of history often obscured by the more prominent narratives of this land. The temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, isn't imposing in the way of some grand Southern Indian temples. Instead, it exudes a quiet dignity, its Nagara style architecture a testament to the enduring influence of North Indian temple traditions. The shikhara, the curvilinear tower rising above the sanctum sanctorum, displays a classic beehive shape, though time and the elements have softened its edges, lending it a sense of venerable age. Unlike the ornate, multi-tiered shikharas of later temples, this one possesses a simpler elegance, its surface punctuated by vertical bands and miniature decorative motifs that hint at a more austere aesthetic. Stepping inside the dimly lit garbhagriha, the sanctum sanctorum, I was struck by the palpable sense of reverence. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers. The lingam, the symbolic representation of Lord Shiva, stood at the center, bathed in the soft glow of oil lamps. The smooth, dark stone seemed to absorb the ambient light, radiating a quiet power. The walls within the sanctum were plain, devoid of elaborate carvings, further emphasizing the focus on the central deity. Circumambulating the sanctum, I observed the outer walls of the temple. Here, the narrative shifted. Panels of intricate carvings depicted scenes from Hindu mythology, predominantly stories related to Lord Shiva. The figures, though weathered, retained a remarkable dynamism. I was particularly captivated by a depiction of Shiva’s cosmic dance, Tandava, the energy of the scene seemingly frozen in stone. The sculptor had masterfully captured the fluidity of movement, the divine frenzy contained within the rigid confines of the stone panel. The temple’s location within the historically significant Kurukshetra adds another layer of intrigue. Local legends link the temple to the Mahabharata, claiming it was built by the Pandavas themselves after the great war. While historical evidence for this claim remains elusive, the connection underscores the temple's enduring presence in the cultural memory of the region. It stands as a silent witness to centuries of change, a testament to the enduring power of faith amidst the ebb and flow of empires and ideologies. As I walked around the temple complex, I noticed several smaller shrines dedicated to other deities within the Hindu pantheon. This syncretic element, common in many Indian temples, speaks to the evolving nature of religious practice, the absorption and assimilation of diverse beliefs over time. The presence of these smaller shrines creates a sense of community, a spiritual ecosystem where different deities coexist within a shared sacred space. Leaving the Sarveshwar Mahadev Temple, I carried with me more than just photographs and notes. I carried a sense of connection to the past, a deeper understanding of the intricate tapestry of Indian history and spirituality. The temple, in its quiet dignity, had spoken volumes, revealing glimpses into the artistic, religious, and cultural landscape of a bygone era. It stands as a reminder that even amidst the clamor of history, the whispers of faith continue to resonate, offering solace and meaning across the ages.

Kizil Caves Baicheng Xinjiang China

Kizil Caves, also known as the Kizil Thousand Buddha Caves, located near Baicheng in Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, represent one of the most magnificent and artistically significant Buddhist cave temple complexes in Central Asia, comprising over 236 rock-cut caves carved into the cliffs of the Muzat River valley from the 3rd to 8th centuries CE, creating a breathtaking religious landscape that demonstrates the extraordinary transmission of Indian Buddhist cave architecture and artistic traditions to Central Asia along the northern branch of the Silk Road. The cave complex, carved entirely from living rock using techniques adapted from Indian cave temple traditions, features a stunning collection of Buddhist caves including meditation cells, assembly halls, and elaborate chapels adorned with some of the most sophisticated and beautiful Buddhist murals discovered in Central Asia, executed using techniques and iconographic programs that were directly transmitted from the great Buddhist art centers of India including Ajanta, Ellora, and the Gandharan region, creating a vivid testament to the cultural exchange that flourished along the Silk Road. The caves, often referred to as the "Oriental Dunhuang" due to their artistic significance, feature extraordinary murals depicting Jataka tales (stories from the Buddha's previous lives), scenes from the life of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and Central Asian merchants that demonstrate the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist iconography and artistic techniques possessed by the artists who created them, while the discovery of inscriptions in multiple languages including Sanskrit, Tocharian, and Chinese provides crucial evidence of the site's role as a multilingual center for the translation and transmission of Indian Buddhist texts. The site's architectural design demonstrates direct influence from Indian Buddhist cave architecture, particularly the traditions of western India such as Ajanta and Ellora, with the overall planning, cave forms, and decorative programs reflecting Indian Buddhist practices that were systematically transmitted to Central Asia, while the sophisticated rock-cutting techniques and mural painting methods demonstrate the transmission of Indian artistic knowledge to Central Asian craftsmen. Archaeological evidence reveals that Kizil served as a major center of Buddhist learning and practice for over five centuries, attracting monks, traders, and pilgrims from across the Buddhist world, while the site's location along the northern Silk Road facilitated its role in the transmission of Buddhist teachings, art, and culture from India to China and beyond. The caves flourished particularly during the 4th to 6th centuries CE, when they served as one of the most important centers for the production of Buddhist art and the transmission of Buddhist teachings in Central Asia, with the site continuing to function as a Buddhist center through the 8th century before gradually declining following political changes and the shifting of trade routes. The site was rediscovered by European explorers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with numerous expeditions documenting and studying the caves, while unfortunately many of the murals were removed and are now housed in museums worldwide, creating a complex legacy that highlights both the site's extraordinary artistic significance and the challenges of cultural heritage preservation. Today, Kizil Caves stand as a UNESCO Tentative List site and represent one of the most important archaeological and artistic sites in Central Asia, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Buddhist art and culture along the Silk Road, while ongoing conservation efforts, archaeological research, and international preservation initiatives continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian Buddhist art and architecture. ([1][2])

Shivneri Fort Junnar

The imposing basalt ramparts of Shivneri Fort, rising dramatically from the Deccan plateau, held me captivated from the moment I arrived in Junnar. Having spent years immersed in the granite wonders of South Indian temple architecture, I was eager to experience this different, yet equally compelling, facet of India's heritage. The fort, a formidable military stronghold for centuries, offered a fascinating glimpse into a world shaped by strategic necessities rather than the spiritual aspirations that drove the Dravidian temple builders. The ascent to the fort itself was an experience. The winding path, carved into the rock, felt like a journey back in time. Unlike the elaborate gopurams and mandapas I was accustomed to, the entrance to Shivneri was a study in practicality. The fortifications, though lacking the ornate carvings of southern temples, possessed a raw beauty, their strength evident in the sheer thickness of the walls and the clever placement of bastions. The strategically positioned 'Shivai Devi' and 'Maha Darwaja' gates, with their sturdy wooden doors reinforced with iron, spoke volumes about the fort's defensive history. Within the fort walls, a different world unfolded. The rugged terrain enclosed a surprisingly self-sufficient community. Water tanks, carved meticulously into the rock, showcased impressive water management techniques, a stark contrast to the temple tanks of the south, which often served ritualistic purposes as well. The 'Badami Talav,' with its intricate stepped sides, was a particularly striking example. The granaries, built to withstand sieges, were another testament to the fort's pragmatic design. The architectural style within the fort was a blend of various influences. While the overall structure was dictated by military needs, glimpses of later architectural embellishments were visible, particularly in the residential areas. The 'Shivai Mata Mandir,' where Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was born, held a special significance. While simpler than the grand temples of the south, it possessed a quiet dignity, its stone construction echoing the fort's overall aesthetic. The carvings on the pillars and lintels, though less intricate than the temple sculptures I was familiar with, displayed a distinct local style. One of the most striking features of Shivneri Fort was its integration with the natural landscape. The architects had skillfully utilized the natural contours of the hill, incorporating the rock formations into the fort's defenses. This symbiotic relationship between architecture and nature was a recurring theme, reminding me of the hilltop temples of South India, where the natural surroundings often played a crucial role in the temple's design and symbolism. Exploring the 'Ambarkhana,' the grain storage, and the 'Kalyan Buruj,' I couldn't help but compare the ingenuity of the Maratha military architects with the temple builders of the south. While the latter focused on creating spaces that inspired awe and devotion, the former prioritized functionality and defense. The lack of elaborate ornamentation at Shivneri, however, did not diminish its architectural merit. The fort's strength lay in its simplicity and its seamless integration with the landscape. My visit to Shivneri Fort was a powerful reminder that architectural brilliance can manifest in diverse forms. While my heart remains deeply connected to the ornate temples of South India, the stark beauty and strategic ingenuity of Shivneri Fort offered a valuable new perspective on India's rich architectural heritage. The echoes of history resonated within those basalt walls, narrating tales of resilience, strategy, and a deep connection to the land. It was an experience that broadened my understanding of Indian architecture and left me with a profound appreciation for the diverse expressions of human ingenuity.

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides