Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

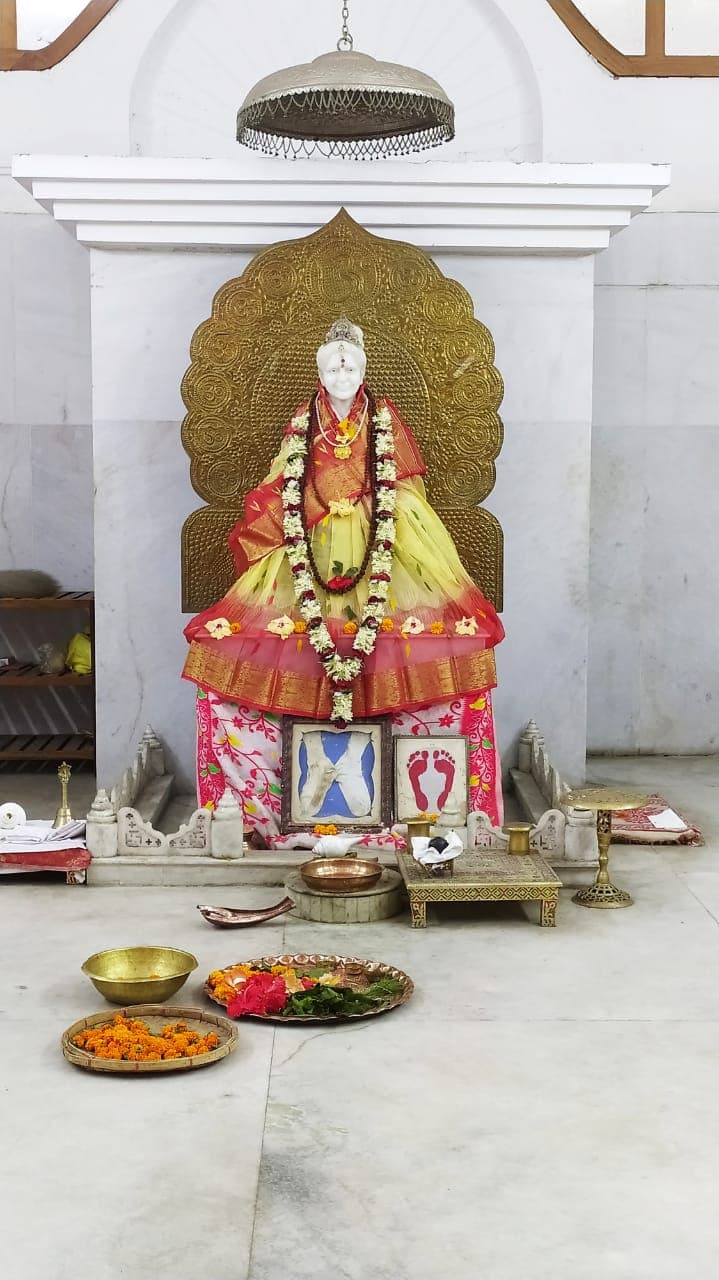

Uma Maheshwari Temple Agartala

The midday sun cast long shadows across the courtyard of the Uma Maheshwari Temple in Agartala, dappling the red brick façade with an intricate play of light and shade. As a cultural journalist from Uttar Pradesh, steeped in the architectural narratives of the Gangetic plains, I found myself captivated by this unexpected burst of North Indian temple architecture nestled within the heart of Tripura. The temple, dedicated to Uma Maheshwari, a combined form of Parvati and Shiva, stands as a testament to the cultural exchange and historical connections that have shaped this northeastern state. The first thing that struck me was the temple's relatively modest scale compared to the sprawling complexes I'm accustomed to back home. Yet, within this compact footprint, the architects have managed to capture the essence of Nagara style architecture. The shikhara, the curvilinear tower rising above the sanctum sanctorum, is the defining feature. While smaller than the towering shikharas of, say, the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple in Khajuraho, it retains the same graceful upward sweep, culminating in a pointed amalaka. The brick construction, however, sets it apart from the sandstone temples of North India, lending it a distinct regional flavour. Close inspection revealed intricate terracotta work adorning the shikhara, depicting floral motifs and divine figures, a craft that echoes the rich terracotta traditions of Bengal. Stepping inside the garbhagriha, the sanctum sanctorum, I was met with a palpable sense of serenity. The deities, Uma and Maheshwar, are enshrined here in a simple yet elegant manner. Unlike the elaborate iconography found in some North Indian temples, the focus here seemed to be on the spiritual essence of the deities, fostering a sense of quiet contemplation. The priest, noticing my interest, explained that the temple was constructed in the 16th century by the Manikya dynasty, rulers of the Tripura Kingdom, who traced their lineage back to the Lunar dynasty of mythology, further strengthening the connection to North Indian traditions. The temple courtyard, enclosed by a low wall, offers a peaceful respite from the bustling city outside. Several smaller shrines dedicated to other deities dot the perimeter, creating a microcosm of the Hindu pantheon. I spent some time observing the devotees, a mix of locals and visitors, engaging in their prayers and rituals. The air was thick with the fragrance of incense and the murmur of chants, creating an atmosphere of devotion that transcended regional boundaries. What intrigued me most was the seamless blending of architectural styles. While the core structure adhered to the Nagara style, elements of Bengali temple architecture were subtly interwoven. The use of brick, the terracotta ornamentation, and the chala-style roof over the mandapa, or assembly hall, all pointed towards a conscious assimilation of local architectural idioms. This architectural hybridity, I realized, mirrored the cultural synthesis that has shaped Tripura's identity over centuries. As I left the Uma Maheshwari Temple, I carried with me not just the visual memory of its elegant form but also a deeper understanding of the complex cultural tapestry of India. The temple stands as a powerful symbol of how cultural influences can traverse geographical boundaries, intermingle, and create something unique and beautiful. It serves as a reminder that while regional variations enrich our heritage, the underlying spiritual and artistic threads that bind us together are far stronger than the differences that might appear to separate us. It is in these spaces, where architectural styles converge and cultural narratives intertwine, that we truly grasp the richness and diversity of the Indian civilization.

Shree Ganesh Mandir Champhai

The air in Champhai, Mizoram, hung heavy with the scent of pine and a palpable sense of serenity. Perched atop a hillock overlooking the sprawling valley, the Shree Ganesh Mandir commands attention, not through towering grandeur, but through a quiet, understated presence. Unlike the ornate, bustling temples I've encountered across India on my UNESCO World Heritage journey, this one exuded a different kind of energy – a peaceful contemplation that resonated with the surrounding landscape. The first thing that struck me was the unusual architecture. This wasn't the typical Dravidian or Nagara style I’d grown accustomed to. The temple, dedicated to Lord Ganesha, incorporates elements of indigenous Mizo architecture, creating a unique hybrid. The sloping roof, reminiscent of traditional Mizo houses, is clad in corrugated iron sheets, a practical adaptation to the region's heavy rainfall. This pragmatic approach extends to the walls, constructed from locally sourced stone, lending the structure an organic, earthy feel. The entrance is framed by a simple archway, devoid of elaborate carvings, leading into a single, modest prayer hall. Inside, the atmosphere is hushed and reverent. The idol of Lord Ganesha, carved from a single block of white marble, occupies the central space. It's a relatively small statue, but its simplicity amplifies its spiritual weight. The absence of opulent decorations and the muted natural light filtering through the windows create an environment conducive to introspection. I sat there for a while, absorbing the quiet energy, the only sound the gentle rustling of prayer flags outside. What truly sets this temple apart, however, is its story. My conversations with the local priest and residents revealed a fascinating narrative of religious harmony. Champhai, predominantly Christian, embraced the construction of this Hindu temple, demonstrating a remarkable level of interfaith acceptance. The land for the temple was donated by a local Mizo family, a testament to the community's inclusive spirit. This narrative of coexistence, woven into the very fabric of the temple, resonated deeply with me. It was a powerful reminder that spirituality transcends religious boundaries. The panoramic view from the temple grounds adds another layer to the experience. The rolling hills, carpeted in vibrant green, stretch as far as the eye can see, punctuated by the occasional cluster of houses. The Myanmar border, a mere stone's throw away, is visible on a clear day, adding a geopolitical dimension to the vista. I spent a considerable amount of time simply gazing at the landscape, lost in the tranquility of the moment. Visiting the Shree Ganesh Mandir wasn't just about ticking off another UNESCO site on my list. It was an immersive cultural experience, a lesson in religious tolerance, and a moment of quiet reflection amidst the breathtaking beauty of Mizoram. The temple, in its unassuming simplicity, speaks volumes about the spirit of Champhai – a community that embraces diversity and finds harmony in its differences. This experience, more than the grandeur of some of the more famous sites, underscored the true essence of my journey – to discover the heart and soul of India, one temple, one monument, one story at a time. The lack of readily available information about this particular UNESCO site adds to its mystique. It's not a place overrun by tourists, which allows for a more intimate and authentic connection with the space and its significance. This, for me, is the true reward of exploring the lesser-known corners of our incredible heritage. The Shree Ganesh Mandir in Champhai is not just a temple; it's a testament to the power of faith, community, and the quiet beauty of coexistence.

Mihintale Buddhist Monastery Anuradhapura Sri Lanka

Mihintale, dramatically situated on a hilltop approximately 12 kilometers east of Anuradhapura, represents one of the most extraordinary and historically significant Buddhist monastery complexes in South Asia, revered as the cradle of Buddhism in Sri Lanka where Mahinda, the son of the Indian Emperor Ashoka, met King Devanampiyatissa in 247 BCE and introduced Buddhism to the island, creating a powerful testament to the profound transmission of Indian Buddhist religious traditions to Sri Lanka. The monastery complex, spanning across multiple hilltops and featuring ancient stupas, meditation caves, rock inscriptions, and religious structures, demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian Buddhist monastery architecture from the great monastic centers of India including the Mauryan period monasteries, while the site's association with Mahinda, who was sent by his father Emperor Ashoka as part of the Buddhist missionary effort, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist missionary traditions that were transmitted from India to Sri Lanka. The monastery's most remarkable feature is its association with the introduction of Buddhism to Sri Lanka, an event that is documented in ancient chronicles including the Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa and represents one of the most important events in the history of Buddhism in South Asia, while the monastery's extensive ruins including stupas, meditation caves, and rock inscriptions provide crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian Buddhist texts and practices to Sri Lanka. Archaeological evidence reveals that the monastery served as a major center of Buddhist learning and practice for over two millennia, attracting monks, scholars, and pilgrims from across Sri Lanka and South India, while the discovery of numerous inscriptions in Pali, Sanskrit, and Sinhala provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian Buddhist texts and practices to Sri Lanka, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist traditions possessed by the Sri Lankan Buddhist establishment. The monastery's architectural layout, with its central stupa surrounded by meditation caves, assembly halls, and monastic cells arranged across multiple hilltops, follows sophisticated Indian Buddhist monastery planning principles that were systematically transmitted from the great monastic centers of India, while the monastery's extensive decorative programs including sculptures, carvings, and architectural elements demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Buddhist iconography and artistic traditions with local Sri Lankan aesthetic sensibilities. The monastery's association with the annual Poson Festival, which commemorates the introduction of Buddhism to Sri Lanka, demonstrates the continued vitality of Indian religious traditions in Sri Lanka, while the monastery's location near Anuradhapura underscores its significance as a major center for the transmission of Buddhist teachings, art, and culture from India to Sri Lanka. Today, Mihintale stands as one of the most important Buddhist pilgrimage sites in Sri Lanka, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Buddhist culture and architecture to Sri Lanka, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Sri Lankan religious and artistic traditions. ([1][2])

Shri Ramnath Temple Bandora

The ochre walls of Shri Ramnath Temple, nestled amidst the emerald embrace of Bandora's foliage, exuded a tranquility that instantly captivated me. This wasn't the imposing grandeur of some of the larger Goan temples, but a quiet dignity, a whispered history etched into the laterite stone and whitewashed plaster. The temple, dedicated to Lord Rama, felt deeply rooted in the land, a testament to the enduring syncretism of Goan culture. My first impression was one of intimate enclosure. A modest courtyard, paved with uneven stones worn smooth by centuries of footsteps, welcomed me. The main entrance, a relatively unadorned gateway, didn't prepare me for the burst of colour within. The deep red of the main temple structure, contrasted against the white of the surrounding buildings, created a vibrant visual harmony. The architecture, while predominantly influenced by the regional Goan style, hinted at subtle elements borrowed from other traditions. The sloping tiled roof, a hallmark of Goan temple architecture, was present, but the detailing around the windows and doorways showcased a delicate intricacy reminiscent of some of the older temples I've encountered in Karnataka. Stepping inside the main sanctum, I was struck by the palpable sense of devotion. The air, thick with the fragrance of incense and flowers, hummed with a quiet energy. The deity of Lord Ramnath, flanked by Sita and Lakshman, held a serene presence. Unlike the ornate, heavily embellished idols found in some temples, these felt more grounded, more accessible. The simple adornments, the soft lighting, and the intimate scale of the sanctum fostered a sense of personal connection, a direct line to the divine. What truly fascinated me, however, were the intricate carvings that adorned the wooden pillars supporting the mandap, or the covered pavilion. These weren't mere decorative flourishes; they narrated stories. Episodes from the Ramayana unfolded in intricate detail, each panel a miniature masterpiece. The battle scenes were particularly captivating, the dynamism of the figures captured with remarkable skill. I spent a considerable amount of time studying these panels, tracing the narrative flow with my fingers, marveling at the artistry and the devotion that had gone into their creation. The temple complex also houses smaller shrines dedicated to other deities, including Lord Ganesha and Lord Hanuman. Each shrine, while distinct, maintained a stylistic coherence with the main temple. This architectural unity, this seamless blending of different elements, spoke volumes about the community that had built and maintained this sacred space. As I wandered through the courtyard, I noticed a small, almost hidden, well. The priest, noticing my interest, explained that the well was considered sacred and its water used for ritual purposes. This integration of natural elements into the temple complex, this reverence for water as a life-giving force, resonated deeply with me. It reminded me of the ancient Indian architectural principles that emphasized the harmonious coexistence of the built environment and the natural world. Leaving the Shri Ramnath Temple, I carried with me not just images of intricate carvings and vibrant colours, but a sense of having touched a living history. This wasn't just a monument; it was a vibrant hub of faith, a testament to the enduring power of belief, and a beautiful example of how architectural traditions can evolve and adapt while retaining their core essence. The quiet dignity of the temple, its intimate scale, and the palpable devotion within its walls left an indelible mark on my mind, a reminder of the rich tapestry of cultural narratives woven into the fabric of India.

Taraknath Temple Tarakeswar

The terracotta panels of the Taraknath Temple, baked a deep, earthy red by the Bengal sun, seemed to hum with stories. Located in the quiet town of Taraknath, within the Hooghly district, this relatively unassuming temple dedicated to Lord Shiva holds a unique charm, distinct from the grander, more famous UNESCO sites I've visited across India. It’s not the scale that captivates here, but the intricate details and the palpable sense of devotion that permeates the air. My journey to Taraknath began with a train ride from Kolkata, followed by a short local bus journey. The temple, dating back to 1729, isn't imposing from a distance. It’s the characteristic 'atchala' Bengal temple architecture – a curved roof resembling a thatched hut – that first catches the eye. As I approached, the intricate terracotta work began to reveal itself. Panels depicting scenes from the epics – the Ramayana and the Mahabharata – unfolded across the temple walls like a visual narrative. Krishna’s playful antics with the gopis, the fierce battle of Kurukshetra, and the serene visage of Shiva meditating – each panel a testament to the skill of the artisans who breathed life into clay centuries ago. The temple's main entrance, a relatively small arched doorway, felt like a portal to another time. Stepping inside, I found myself in a courtyard, the central shrine dominating the space. The shivalinga, the symbolic representation of Lord Shiva, resided within the sanctum sanctorum, a dimly lit chamber that exuded an aura of reverence. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers, a constant reminder of the temple's living, breathing spirituality. Unlike some of the more heavily touristed UNESCO sites, Taraknath retained a sense of intimacy. I spent hours wandering around the courtyard, tracing the weathered terracotta panels with my fingers, trying to decipher the stories they told. The level of detail was astonishing. Individual expressions on the faces of the figures, the delicate folds of their garments, the intricate patterns of the borders – each element meticulously crafted. I noticed that some panels had suffered the ravages of time, with portions chipped or eroded, yet this only added to their character, whispering tales of resilience and endurance. One aspect that struck me was the secular nature of the depicted scenes. Alongside the mythological narratives, there were depictions of everyday life in 18th-century Bengal – farmers tilling their fields, women engaged in household chores, musicians playing instruments. This blend of the divine and the mundane offered a fascinating glimpse into the social fabric of the time. Beyond the main shrine, I explored the smaller surrounding temples dedicated to other deities. Each had its own unique charm, though the terracotta work on the main temple remained the highlight. I observed several local families performing pujas, their faces etched with devotion. It was a privilege to witness these rituals, a reminder of the deep-rooted cultural significance of the temple. As the sun began to set, casting long shadows across the courtyard, I sat on a stone bench, absorbing the tranquility of the place. Taraknath Temple isn't just a historical monument; it's a living testament to the artistic and spiritual heritage of Bengal. It's a place where mythology and history intertwine, where terracotta whispers stories of bygone eras, and where the devotion of generations resonates within its ancient walls. My visit to Taraknath was a reminder that sometimes, the most profound experiences are found not in the grandest of structures, but in the quiet corners where history and faith converge.

Kundankuzhi Mahadevar Temple Nagercoil

The humid Kanyakumari air hung heavy as I approached the Kundankuzhi Mahadevar Temple, tucked away in a quiet village near Nagercoil. The temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, doesn't boast the towering gopurams of some of Tamil Nadu's more famous temples, but it possesses a quiet dignity and architectural nuances that captivated me from the first glance. The relatively modest size allows for an intimate exploration, a chance to truly connect with the structure and its history. The first thing that struck me was the distinct Kerala architectural influence, a testament to the region's historical fluidity and cultural exchange. The sloping tiled roofs, reminiscent of Kerala's traditional houses and temples, were a departure from the typical Dravidian style I'm accustomed to seeing in Chennai. The muted ochre walls, devoid of elaborate carvings on the exterior, further emphasized this unique blend. This simplicity, however, wasn't stark; it felt more like a conscious choice, directing the visitor's attention inwards, towards the spiritual heart of the temple. Stepping inside the main mandapam, I was greeted by a series of intricately carved pillars. While the exterior was understated, the interior showcased the artisans' skill. The pillars, though weathered by time, displayed a variety of motifs – stylized lotuses, mythical creatures, and intricate geometric patterns. I noticed a subtle difference in the carving styles on some pillars, suggesting additions or renovations over different periods. This layering of history, visible in the very fabric of the temple, added to its charm. The garbhagriha, the sanctum sanctorum, housed the lingam, the symbolic representation of Lord Shiva. The air within was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers. The dimly lit space, illuminated by oil lamps, created an atmosphere of reverence and tranquility. I spent some time observing the worn stone floor, polished smooth by centuries of devotees' feet, a tangible connection to the generations who had worshipped here before me. Moving towards the outer prakaram, I discovered a small shrine dedicated to the Goddess Parvati. The carvings here were noticeably different, featuring a more flowing, feminine aesthetic. The presence of both Shiva and Parvati, representing the complementary forces of creation and destruction, underscored the temple's adherence to traditional Shaivite principles. One of the most intriguing aspects of the Kundankuzhi Mahadevar Temple was its integration with the natural surroundings. Ancient trees shaded the temple grounds, their roots intertwining with the stone structures, creating a sense of harmony between the built and natural environments. A small pond, located to the west of the main temple, added to the serene atmosphere. It was easy to imagine how this tranquil setting would have provided a sanctuary for both spiritual contemplation and community gatherings over the centuries. My visit to the Kundankuzhi Mahadevar Temple wasn't just about observing architectural details; it was an immersive experience. The temple's unassuming exterior belied a rich history and a palpable spiritual energy. It offered a glimpse into the cultural exchange between Tamil Nadu and Kerala, showcasing a unique blend of architectural styles. Unlike the grand, often crowded temples of larger cities, Kundankuzhi allowed for a quiet, personal connection, a chance to appreciate the subtleties of craftsmanship and the enduring power of faith. It's a testament to the fact that architectural marvels don't always need to be grand in scale to be profoundly impactful. They can be found in quiet corners, whispering stories of history, faith, and artistic expression.

Maa Tara Tarini Temple Ganjam

The wind whipped my dupatta around me as I climbed the final steps to the Maa Tara Tarini temple, perched high on a hill overlooking the Rushikulya River. Having explored countless forts and palaces in Rajasthan, I’m always eager to experience new forms of heritage, and this Shakti Peetha in Odisha held a particular allure. The climb itself, though steep, was punctuated by the vibrant energy of devotees, their chants and the clang of bells creating a palpable buzz in the air. The temple complex is relatively small, a stark contrast to the sprawling citadels I’m accustomed to. Two brightly painted terracotta idols of the twin goddesses, Tara and Tarini, reside within the sanctum sanctorum. Unlike the elaborate marble carvings and sandstone latticework of Rajasthani architecture, the temple here embraces a simpler aesthetic. The main structure, while recently renovated, retains its traditional essence. The use of laterite stone and the distinctive sloping roof, reminiscent of the region's vernacular architecture, grounded the sacred space in its local context. What struck me most was the panoramic view from the hilltop. The Rushikulya River snaked its way through the verdant landscape below, glinting silver under the afternoon sun. The Bay of Bengal shimmered in the distance, a vast expanse of blue merging with the sky. This vantage point, I realized, was integral to the temple's significance. It felt as though the goddesses were watching over the land, their protective gaze extending to the horizon. I spent some time observing the rituals. Unlike the structured puja ceremonies I’ve witnessed in Rajasthan, the practices here felt more organic, driven by fervent devotion. Animal sacrifice, a practice largely absent in my home state, is still prevalent here, a stark reminder of the diverse tapestry of Indian religious traditions. While personally unsettling, it offered a glimpse into the deep-rooted beliefs and practices of the region. The temple walls are adorned with vibrant murals depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, particularly those related to the goddesses Tara and Tarini. The colours, though faded in places, still held a vibrancy that spoke to the enduring power of these narratives. I noticed that the artistic style differed significantly from the miniature paintings and frescoes I’ve seen in Rajasthan. The lines were bolder, the figures more stylized, reflecting a distinct regional artistic vocabulary. One of the priests, noticing my keen interest, explained the significance of the twin goddesses. They are considered manifestations of Shakti, the divine feminine energy, and are revered as protectors, particularly by seafarers and fishermen. He pointed out the numerous small terracotta horses offered by devotees, symbols of their wishes fulfilled. This resonated with me; the practice of offering votive objects is common across India, a tangible expression of faith and hope. As I descended the hill, the rhythmic chanting of the devotees still echoed in my ears. My visit to the Maa Tara Tarini temple was a departure from the grandeur of Rajasthan's palaces, yet it offered a different kind of richness. It was a journey into the heart of a vibrant, living tradition, a testament to the diverse expressions of faith that weave together the fabric of India. The simplicity of the architecture, the raw energy of the rituals, and the breathtaking natural setting combined to create a truly unique and unforgettable experience. It reinforced the understanding that heritage isn't just about magnificent structures, but also about the intangible cultural practices that give them meaning.

Shwezigon Pagoda Bagan

Shwezigon Pagoda, located in Nyaung-U within the Bagan Archaeological Zone, represents one of the most significant Buddhist pagodas in Myanmar, constructed in the 11th century CE during the reign of King Anawrahta and featuring extensive enshrinement of Hindu nats (spirits) alongside Buddha relics, demonstrating the integration of Hindu animistic traditions into Buddhist religious practice that characterized Myanmar’s relationship with the greater Hindu rashtra extending across the Indian subcontinent. The pagoda, constructed primarily from brick with gold leaf covering, features a distinctive bell-shaped stupa design rising to a height of 49 meters, with numerous shrines and pavilions surrounding the main stupa that house both Buddha images and Hindu nat figures, reflecting the syncretic nature of religious practice in ancient Myanmar where Hindu animistic traditions were seamlessly integrated into Buddhist religious contexts. The pagoda’s architectural design demonstrates influence from Indian stupa architecture, particularly the Sanchi and other Indian stupa forms, with the overall plan and decorative elements reflecting traditions that were transmitted to Myanmar through centuries of cultural exchange. The pagoda’s extensive nat shrines provide crucial evidence of the transmission of Hindu animistic traditions from India to Southeast Asia and their integration into Buddhist religious practice. Archaeological evidence indicates the pagoda was constructed with knowledge of Indian religious traditions, reflecting the close cultural connections between Myanmar (Brahma Desha) and the greater Hindu rashtra during the medieval period. The pagoda has undergone multiple restorations and continues to serve as one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Myanmar, attracting devotees who venerate both Buddhist and Hindu nat traditions. Today, Shwezigon Pagoda stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site within the Bagan Archaeological Zone, serving as a powerful symbol of Myanmar’s deep connections to Indian civilization and its historical role as part of the greater Hindu rashtra that extended across the Indian subcontinent and into Southeast Asia through shared religious, cultural, and animistic traditions. ([1][2])

Mahabali Temple Imphal

The air hung heavy with the scent of incense and damp earth as I stepped onto the grounds of the Mahabali Temple in Imphal. The temple, dedicated to the ancient pre-Vaishnavite deity Mahabali, exuded an aura of quiet power, a palpable sense of history clinging to its weathered stones. Unlike the ornate, towering structures I’m accustomed to photographing in Madhya Pradesh, this temple possessed a grounded, almost elemental presence. Its pyramidal roof, constructed of corrugated iron sheets now rusted with age, seemed an incongruous addition to the ancient brick foundation. This juxtaposition, however, spoke volumes about the temple's enduring journey through time, adapting and evolving while retaining its core spiritual significance. The temple's brickwork, the primary focus of my lens, was a marvel. The bricks, uneven in size and texture, were laid without mortar, a testament to the ingenuity of the ancient Meitei builders. Centuries of weathering had eroded some, leaving intriguing patterns and textures that caught the light in fascinating ways. I spent a considerable amount of time circling the structure, observing how the sunlight interacted with these imperfections, highlighting the subtle variations in the brick’s hues, from deep terracotta to a faded, almost pinkish orange. The lack of mortar allowed for a certain flexibility, a give-and-take with the elements that perhaps contributed to the temple's longevity. It felt as if the structure was breathing, subtly shifting and settling with the earth beneath it. A small, unassuming entrance led into the inner sanctum. The interior was dimly lit, the air thick with the scent of offerings and the murmur of prayers. Photography wasn't permitted inside, which, in a way, amplified the sacredness of the space. It forced me to engage with the temple on a different level, to absorb the atmosphere, the energy, and the palpable devotion of the worshippers. I sat quietly for a while, observing the flickering oil lamps and listening to the rhythmic chanting, letting the weight of history and tradition settle upon me. Outside, the temple grounds were a hive of activity. Devotees moved with a quiet reverence, offering flowers, fruits, and incense at the base of the structure. I noticed several small shrines scattered around the main temple, each dedicated to a different deity, creating a complex tapestry of spiritual beliefs. This intermingling of faiths, the layering of traditions, is something I find particularly captivating about the Northeast. It speaks to a cultural fluidity, an acceptance of diverse spiritual paths that is both refreshing and inspiring. As I photographed the devotees, I was struck by the vibrant colours of their traditional attire, a stark contrast to the muted tones of the temple itself. The women, draped in intricately woven phanek (sarongs) and innaphi (shawls), moved with grace and dignity, their presence adding another layer of richness to the scene. I made a conscious effort to capture these moments respectfully, aiming to convey the spirit of devotion without intruding on the sanctity of their rituals. The Mahabali Temple is more than just an architectural marvel; it's a living testament to the enduring power of faith and tradition. It’s a place where the past and present intertwine, where ancient rituals are performed alongside modern-day life. My time at the temple was a humbling experience, a reminder of the deep spiritual connections that bind communities together and the importance of preserving these cultural treasures for generations to come. The photographs I captured, I hope, will serve as a visual echo of this experience, conveying not just the physical beauty of the temple, but also the intangible spirit that resides within its ancient walls.

Gangaramaya Temple Colombo Sri Lanka

Gangaramaya Temple, majestically situated in the heart of Colombo, represents one of the most extraordinary and culturally significant Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka, established in the late 19th century CE as a harmonious blend of Sri Lankan, Thai, Indian, and Chinese architectural styles, creating a powerful testament to the profound transmission of Indian Buddhist religious and architectural traditions to Sri Lanka and demonstrating the sophisticated multicultural synthesis that has characterized Sri Lankan religious practices. The temple complex, featuring a Vihara (temple), Cetiya (pagoda), Bodhi tree, and museum, demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian Buddhist temple architecture, particularly the traditions of northern India and Southeast Asia, with local adaptations that reflect the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Buddhist religious and artistic traditions with Sri Lankan, Thai, and Chinese building techniques, while the temple's most remarkable feature is its Seema Malaka, an assembly hall for monks designed by the renowned architect Geoffrey Bawa and funded by a Muslim patron, exemplifying the interfaith harmony and multicultural synthesis that has characterized Sri Lankan religious practices. The temple's architectural layout, with its eclectic design incorporating elements from multiple Asian architectural traditions, follows sophisticated planning principles that demonstrate the transmission of Indian Buddhist temple planning from the great temple complexes of India and Southeast Asia, while the temple's extensive decorative programs including sculptures, carvings, and architectural elements demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Buddhist iconography and artistic traditions with local and regional aesthetic sensibilities. Archaeological evidence reveals that the temple has served as a major center of Buddhist worship and learning for over a century, engaging in various welfare activities including operating old age homes, vocational schools, and orphanages, while the temple's association with the annual Navam Perahera, one of the largest Buddhist festivals in Colombo, demonstrates the continued vitality of Indian religious traditions in Sri Lanka. The temple's unique character as a center for Buddhist learning and social welfare demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist social engagement traditions that were transmitted to Sri Lanka, while the temple's location in the heart of Colombo underscores its significance as a major center for the transmission of Buddhist teachings and culture in modern Sri Lanka. Today, Gangaramaya Temple stands as one of the most important Buddhist temples in Colombo, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Buddhist culture and architecture to Sri Lanka, while ongoing conservation efforts continue to protect and maintain this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Sri Lankan religious and artistic traditions. ([1][2])

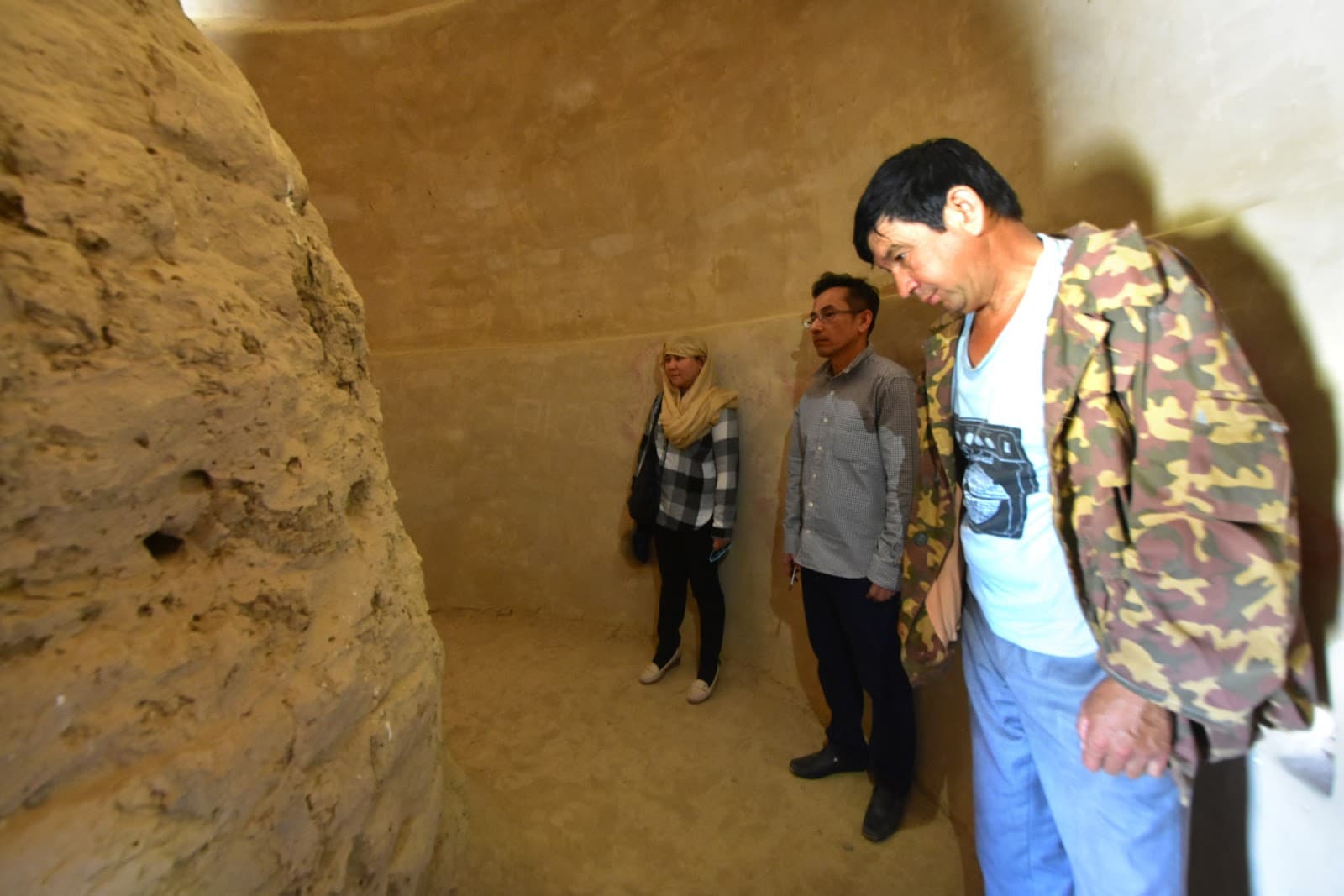

Kara Tepe Monastery Termez Uzbekistan

Kara Tepe Monastery, dramatically carved into the rocky hillsides near Termez in southern Uzbekistan, represents one of the most extraordinary and architecturally unique Buddhist monastic complexes in Central Asia, constructed from the 2nd to 5th centuries CE through the remarkable technique of rock-cut architecture that demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian Buddhist cave monastery traditions from the great rock-cut complexes of India including Ajanta, Ellora, and Karle to Central Asia. The monastery complex, comprising multiple levels of interconnected caves and chambers carved directly into the natural rock formations, features extraordinary architectural elements including meditation cells, assembly halls, stupa chambers, and living quarters that demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Buddhist rock-cut architecture, particularly the traditions of western and central India, with local Central Asian adaptations that reflect the remarkable skill and dedication of the monks and artisans who created this underground spiritual city. The site's most remarkable feature is its extensive network of rock-cut chambers, some decorated with elaborate stucco reliefs and paintings that demonstrate the direct transmission of Indian Buddhist iconography and artistic traditions, while the architectural layout, with its central assembly halls surrounded by smaller cells and stupa chambers, follows the classic Indian Buddhist cave monastery plan that was systematically transmitted from the great rock-cut complexes of India. Archaeological excavations have revealed extraordinary Buddhist sculptures and reliefs executed in styles that demonstrate clear connections to Indian artistic traditions, while the discovery of numerous artifacts including inscriptions, ritual objects, and evidence of daily monastic life provides crucial evidence of the site's role as a major center of Buddhist learning and practice that attracted monks from across the Buddhist world. The monastery's location near Termez, a major Silk Road crossroads, underscores its significance as a center for the transmission of Buddhist teachings, art, and culture from India to Central Asia, while the site's remarkable rock-cut architecture demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian Buddhist traditions and the remarkable engineering skills possessed by the monks and artisans who created this extraordinary underground complex. Today, Kara Tepe stands as a UNESCO Tentative List site and represents one of the most important rock-cut Buddhist monasteries in Central Asia, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Buddhist culture and architecture to Central Asia, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian religious and artistic traditions. ([1][2])

Kaiyuan Temple Quanzhou Fujian China

Kaiyuan Temple, dramatically situated in the historic city of Quanzhou in southeastern Fujian Province, represents one of the most extraordinary and archaeologically significant Buddhist temple complexes in China, dating from the 7th century CE and serving as a major center along the Maritime Silk Road that flourished as a cosmopolitan hub where Indian Hindu and Buddhist traditions, Chinese cultural influences, and Southeast Asian maritime cultures converged, creating a powerful testament to the profound transmission of Indian religious civilization to China during the medieval period. The site, featuring sophisticated Buddhist temple structures with the remarkable preservation of ancient Hindu stone columns that demonstrate clear connections to the architectural traditions of ancient India, particularly the sophisticated column design principles and decorative programs that were transmitted from the great temple centers of southern India, demonstrates the direct transmission of Indian architectural knowledge, religious iconography, and cultural concepts from the great centers of ancient India, particularly the sophisticated temple architecture traditions that were systematically transmitted to China through the extensive maritime trade networks that connected India with China, while the site's most remarkable feature is its extraordinary collection of ancient Hindu stone columns, originally from a Hindu temple that once stood on the site, featuring sophisticated carvings of Hindu deities, mythological scenes, and architectural elements that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian temple architecture traditions, particularly the structural techniques and decorative programs that were central to Indian temple architecture. The temple structures' architectural layout, with their sophisticated planning, central halls surrounded by subsidiary structures, and the integration of Hindu architectural elements into Buddhist temple design, follows planning principles that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian temple planning principles, particularly the structural techniques and decorative traditions that were central to Indian temple architecture, while the site's extensive archaeological remains including the Hindu stone columns, Buddhist sculptures, and architectural elements demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Hindu and Buddhist iconography and cosmological concepts with local Chinese aesthetic sensibilities and building materials. Archaeological evidence reveals that the site served as a major center of religious activity and cultural exchange during the 7th through 13th centuries, attracting traders, monks, and pilgrims from across China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, while the discovery of numerous artifacts including the Hindu stone columns with clear Indian stylistic influences, Buddhist sculptures that reflect Indian iconographic traditions, and architectural elements that reflect Indian architectural concepts provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to China, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian temple architecture and religious practices possessed by the site's patrons and religious establishment. The site's association with the ancient city of Quanzhou, which flourished as a major trading port along the Maritime Silk Road with extensive connections to India and Southeast Asia, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious traditions that were transmitted to China, while the site's Hindu stone columns and Buddhist temple structures demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian temple architecture traditions that were central to ancient Indian civilization. The site has been the subject of extensive archaeological research and conservation efforts, with ongoing work continuing to reveal new insights into the site's sophisticated architecture, religious practices, and its role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to China, while the site's status as part of the Quanzhou UNESCO World Heritage Site demonstrates its significance as a major center for the transmission of Indian religious and cultural traditions to China. Today, Kaiyuan Temple stands as one of the most important religious sites in China, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian religious civilization to China, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Chinese religious and cultural development. ([1][2])

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides