Heritage Sites in Himachal-Pradesh

Dive deep into Indian architectural heritage with 15 comprehensively documented sites located in himachal pradesh. These heritage sites showcase remarkable craftsmanship, innovative construction techniques, and profound historical significance. Our digital archive provides researchers, students, and enthusiasts with detailed architectural documentation, historical research, and preservation insights.

15 sites with scholarly documentation

Detailed architectural analysis

Comprehensive measurements

77% average documentation completeness

Total Sites:15

ASI Protected:2

Top Category:Temple (10)

Top Style:Shikhara + Nagara + Curvilinear tower, upward-pointing. (1)

Top Period:Dogra Period (5)

Avg. Documentation:77%

15

Total Sites

2

ASI Protected

15

Featured

15 Sites Found

Featured

80% Documented

Deotsidh, Hamirpur, Hamirpur (177001), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp Himalayan air, scented with pine and incense, carried the rhythmic chanting of "Jai Baba Balak Nath" as I approached the Baba Balak Nath Temple in Hamirpur. Nestled amidst the Shivalik foothills, this relatively modern temple, unlike the ancient granite marvels of my native Chennai, presented a unique blend of vernacular Himachali architecture and contemporary design. The stark white facade, punctuated by vibrant saffron flags fluttering in the wind, stood in stark contrast to the verdant landscape. My South Indian sensibilities, accustomed to the Dravidian style – the towering gopurams, the intricate carvings, and the dark, cool interiors – were immediately met with something different. Here, the temple complex sprawled horizontally, a series of interconnected structures built around a central courtyard. The main shrine, dedicated to Baba Balak Nath, a revered local deity, is a relatively simple structure, devoid of the elaborate ornamentation I'm used to seeing in South Indian temples. Instead of the granite and sandstone common in the south, the temple here utilizes locally sourced materials – primarily concrete and marble – giving it a distinct regional character. The shikhara, the tower above the sanctum sanctorum, is noticeably different. While South Indian temples feature pyramidal or barrel-vaulted vimanas, here, the shikhara takes on a curvilinear form, reminiscent of the North Indian Nagara style, though less ornate. This amalgamation of architectural styles speaks to the syncretic nature of Indian religious traditions. One of the most striking features of the temple complex is the series of murals depicting scenes from the life of Baba Balak Nath. While the artistic style isn't as refined as the ancient frescoes found in temples like the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur, they possess a raw, vibrant energy that captures the devotion of the local community. The narrative unfolds across the walls, bringing the legends and miracles associated with the deity to life. The use of bold colours – primarily reds, yellows, and blues – against the white backdrop creates a visually arresting experience. The courtyard, the heart of the temple complex, buzzed with activity. Devotees from all walks of life, many clad in traditional Himachali attire, circumambulated the main shrine, offering prayers and chanting hymns. The atmosphere was charged with a palpable sense of faith and reverence. Unlike the hushed sanctity of South Indian temples, here, the devotion was expressed more openly, with a vibrant energy that resonated throughout the complex. I observed a unique ritual practice here: devotees offering roasted chickpeas (chana) to the deity. This is a stark departure from the offerings of coconuts, fruits, and flowers commonly seen in South Indian temples, highlighting the regional variations in religious customs. The absence of elaborate sculptures, a hallmark of Dravidian architecture, was initially surprising. However, the simplicity of the structure, coupled with the stunning natural backdrop of the Himalayas, created a different kind of aesthetic experience. The focus here seemed to be less on architectural grandeur and more on the spiritual experience, on the connection between the devotee and the deity. My visit to the Baba Balak Nath Temple offered a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of temple architecture in India. While it lacked the intricate artistry and historical depth of the South Indian temples I'm familiar with, it showcased a unique regional style that reflected the local culture, beliefs, and landscape. It reinforced the idea that sacred architecture, in all its diverse forms, serves as a powerful testament to human faith and creativity.

Temple

Dogra Period

Featured

80% Documented

Baijnath, Kangra (176125), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air of Kangra Valley held a distinct chill as I approached the Baijnath Temple, its shikhara a dark silhouette against the snow-dusted Dhauladhars. Having spent years documenting the intricate stonework of Gujarat's temples, I was eager to experience this Nagara-style marvel in the Himalayas. The temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva as Vaidyanath, the "Lord of physicians," promised a different flavour of devotion and architectural ingenuity. A flight of stone steps led me to the main entrance, flanked by two small shrines. The first striking feature was the arched doorway, intricately carved with figures of deities and celestial beings. Unlike the ornate toranas of Gujarat's Solanki period temples, these carvings felt more deeply embedded in the stone, almost growing out of it. The weathered sandstone, a warm ochre hue, spoke of centuries of sun, wind, and prayer. Stepping inside the mandapa, or assembly hall, I was immediately struck by a sense of intimacy. The space, while grand, felt contained, perhaps due to the lower ceiling compared to the expansive halls of Modhera Sun Temple back home. The pillars, though simpler in design than the elaborately carved columns of Gujarat, possessed a quiet strength, their surfaces adorned with depictions of Shiva's various forms. Sunlight streamed in through the intricately latticed stone windows, casting dancing patterns on the floor. The garbhagriha, the sanctum sanctorum, housed the lingam, the symbolic representation of Lord Shiva. The air here was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers. Observing the devotees, their faces etched with reverence, I felt a palpable connection to the spiritual heart of the temple. It was a reminder that despite the geographical and stylistic differences, the essence of devotion remained the same. Circumambulating the temple, I examined the exterior walls. The Nagara style, with its curvilinear shikhara rising towards the heavens, was evident, yet distinct from its Gujarati counterparts. The shikhara here felt more grounded, less flamboyant, perhaps mirroring the steadfastness of the mountains themselves. The carvings, while present, were less profuse than the narrative panels adorning the temples of Gujarat. Instead, the emphasis seemed to be on the overall form and the interplay of light and shadow on the stone. One particular detail caught my eye: a series of miniature shikharas adorning the main shikhara, almost like a fractal representation of the temple itself. This was a feature I hadn't encountered in Gujarat's temple architecture, and it added a unique dimension to the Baijnath Temple's visual vocabulary. The temple's location, nestled amidst the towering Himalayas, added another layer to its character. Unlike the sun-drenched plains of Gujarat, where temples often stand as solitary beacons, Baijnath Temple felt integrated into the landscape, almost as if it had sprung from the earth itself. The backdrop of snow-capped peaks and the sound of the gurgling Binwa River flowing nearby created a sense of tranquility that amplified the spiritual experience. As I descended the steps, leaving the temple behind, I carried with me not just images of its architectural beauty, but also a deeper understanding of the diverse expressions of faith and artistry across India. The Baijnath Temple, with its quiet grandeur and its harmonious blend of human craftsmanship and natural beauty, served as a powerful reminder of the enduring legacy of India's temple architecture. It was a testament to the human desire to connect with the divine, expressed through the language of stone, in the heart of the Himalayas.

Temple

Gurjara-Pratihara Period

Featured

80% Documented

Shrigul, Shimla, Sarahan (172105), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air of Sarahan, nestled within the Shimla district of Himachal Pradesh, carries a distinct scent of pine and a whisper of ancient stories. Here, perched on a verdant spur overlooking the Satluj Valley, stands the Bhimakali Temple, a structure that defies easy categorization. It's not just a temple; it's a living museum, a testament to a unique architectural confluence, and a powerful spiritual center. My journey from the sun-baked plains of Gujarat to this Himalayan haven was more than a change in landscape; it was a passage into a different realm of architectural expression. The Bhimakali Temple isn't the typical stone edifice one might expect. Its tiered wooden roofs, reminiscent of the kath-khuni style prevalent in the region, rise against the backdrop of snow-capped peaks, creating a striking visual contrast. This architectural hybrid – part hill architecture, part Hindu temple – is what truly captivated me. The intricate woodwork, darkened by time and weather, tells a silent story of generations of artisans who poured their skill and devotion into its creation. Elaborate carvings of deities, mythical creatures, and floral motifs adorn the wooden facades, each panel a miniature masterpiece. As I ascended the stone steps leading to the main entrance, I noticed the distinct influence of both Hindu and Buddhist architectural elements. The sloping roofs, adorned with metal finials, are characteristic of Himalayan architecture, while the ornate doorways and the presence of images of Hindu deities firmly place it within the Hindu pantheon. This fusion is not merely aesthetic; it reflects the region's rich cultural tapestry, where different traditions have intertwined over centuries. Inside the temple complex, a series of courtyards and chambers unfold, each with its own unique character. The main sanctum, dedicated to Bhimakali, exudes an aura of reverence. Photography is restricted within the inner sanctum, which, in a way, enhances the experience. It compels you to be fully present, to absorb the atmosphere, the chanting of the priests, and the palpable devotion of the pilgrims. The goddess Bhimakali, a fierce manifestation of Durga, is represented not by an idol but by a brass image placed on a raised platform. This unique representation further distinguishes the temple from the traditional iconography found in other parts of India. Beyond the main shrine, the complex houses smaller temples dedicated to other deities, including Lakshmi Narayan and Lord Shiva. Each shrine, while smaller in scale, exhibits the same meticulous craftsmanship and attention to detail. I spent hours exploring the complex, tracing the intricate carvings with my fingers, trying to decipher the stories they whispered. The stone pathways, worn smooth by centuries of footsteps, seemed to echo with the prayers and aspirations of countless devotees. One of the most striking features of the Bhimakali Temple is its setting. The panoramic views of the surrounding mountains, the crisp mountain air, and the sound of prayer flags fluttering in the wind create an atmosphere of profound tranquility. It's a place where the boundaries between the physical and the spiritual seem to blur, where the grandeur of nature complements the human-made marvel. My experience at the Bhimakali Temple was more than just a visit to a historical site; it was an immersion into a living tradition. It's a place where architecture transcends its functional purpose and becomes a powerful medium for storytelling, spiritual expression, and cultural preservation. As I descended the stone steps, leaving the temple behind, I carried with me not just photographs and memories, but a deeper understanding of the rich architectural and cultural heritage of the Himalayas, a heritage that continues to thrive in the heart of these majestic mountains.

Temple

Rajput Period

Featured

80% Documented

Vill. Chamunda Devi, Kangra, Kangra (176051), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air vibrated with a low hum of chanting as I approached the Chamunda Devi Temple, perched precariously on the edge of the Baner River gorge near Kangra. Having explored countless temples across Uttar Pradesh, I was eager to experience this revered Shakti Peetha, a site steeped in legend and nestled within the dramatic Himalayan landscape. The journey itself, winding through terraced fields and pine forests, felt like a pilgrimage, preparing me for the spiritual weight of the place. The temple’s architecture, while not as ornate as some of the Mughal-influenced structures I'm accustomed to in Uttar Pradesh, held a raw, almost primal energy. Built predominantly of stone, its sloping slate roof and wooden facades seemed to grow organically from the cliff face. The structure felt less like a monument imposed upon the landscape and more like an extension of it, a testament to the deep connection between nature and worship in this region. Entering the main courtyard, I was immediately struck by the vibrant colours. Garlands of marigolds and roses adorned the deities, their bright hues contrasting sharply with the dark stone. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the sounds of devotional music, creating an atmosphere both chaotic and serene. Devotees, many having travelled long distances, offered prayers with an intensity I found deeply moving. Their faith, palpable and unwavering, resonated within the very stones of the temple. The main shrine houses the fearsome idol of Chamunda Devi, a form of Durga. Unlike the benevolent, regal depictions of Durga common in Uttar Pradesh, this representation was fierce, almost terrifying. With her garland of skulls and emaciated form, she embodied the destructive power of the goddess, a stark reminder of the cycle of creation and destruction. It was a powerful, visceral experience, far removed from the gentler iconography I was used to. I spent some time observing the intricate carvings that adorned the temple walls. While some depicted scenes from Hindu mythology, others showcased local flora and fauna, highlighting the regional influence on the temple’s artistic vocabulary. The craftsmanship, though weathered by time and the elements, still bore witness to the skill of the artisans who had poured their devotion into every chisel stroke. I noticed a distinct stylistic difference from the temple carvings in Uttar Pradesh, which often feature more elaborate ornamentation and smoother, more polished surfaces. Here, the carvings felt rougher, more expressive, mirroring the rugged terrain surrounding the temple. Beyond the main shrine, I explored the smaller surrounding temples dedicated to other deities. Each had its own unique character, offering a glimpse into the complex tapestry of Hindu beliefs. I was particularly drawn to a small shrine dedicated to Bhairava, Chamunda’s consort, whose fierce image mirrored that of the main deity. The juxtaposition of these two powerful forces, representing the dual aspects of divine energy, was both fascinating and awe-inspiring. As I descended the steps from the temple, the chanting faded into the background, replaced by the rush of the Baner River below. Looking back at the Chamunda Devi Temple, clinging to the cliff edge, I felt a profound sense of peace. The experience had been both humbling and invigorating, a reminder of the enduring power of faith and the diverse expressions of spirituality across India. The temple, with its raw energy and dramatic setting, offered a unique perspective on Hindu worship, distinct from the traditions I knew from my home state. It was a journey into the heart of the Himalayas, a journey not just geographical, but spiritual.

Temple

Dogra Period

Featured

80% Documented

Hadimba Temple Road, Kullu, Manali (175131), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air of Manali carried the scent of pine as I approached the Hidimba Devi Temple, a structure that seemed to rise organically from the dense cedar forest surrounding it. Unlike the ornate stone temples I'm accustomed to in Gujarat, this one was strikingly different, a testament to the unique architectural traditions of the Himalayas. The four-tiered pagoda-style roof, crafted entirely of wood, commanded attention. Each tier, diminishing in size as it ascended, was covered with intricately carved wooden shingles, creating a textured, almost woven effect. The broad eaves, also wooden, projected outwards, offering a sense of shelter and echoing the protective embrace of the surrounding forest. Circling the temple, I observed the intricate carvings that adorned the wooden panels. Depictions of animals, deities, and floral motifs were etched with remarkable detail, narrating stories that I longed to decipher. The deep brown wood, darkened by time and weather, lent an air of ancient wisdom to these narratives. A particularly striking panel portrayed the goddess Durga riding a lion, a powerful image that resonated with the raw, untamed beauty of the landscape. These carvings, unlike the precise and polished stonework I’ve seen in Gujarat’s temples, possessed a rustic charm, a direct connection to the natural world. The foundation of the temple, constructed of stone, provided a sturdy base for the towering wooden structure. This marriage of stone and wood, a blend of the earthbound and the ethereal, felt deeply symbolic. The stone represented the enduring strength of the mountains, while the wood spoke to the transient nature of life, a constant cycle of growth and decay. This duality, so evident in the temple's architecture, seemed to reflect the very essence of the Himalayan landscape. Entering the small, dimly lit sanctum, I was struck by the absence of a traditional idol. Instead, a large rock, believed to be the imprint of the goddess Hidimba Devi, served as the focal point of worship. This reverence for a natural formation, rather than a sculpted image, further emphasized the temple's connection to the surrounding environment. The air within the sanctum was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers, creating an atmosphere of quiet contemplation. Outside, the temple grounds were alive with activity. Local vendors sold colorful trinkets and offerings, while families gathered to offer prayers and seek blessings. The vibrant energy of the present contrasted beautifully with the ancient stillness of the temple itself, creating a dynamic interplay between the past and the present. I observed a young girl carefully placing a flower at the base of a cedar tree, a simple act of devotion that spoke volumes about the deep-rooted reverence for nature in this region. As I descended the stone steps, leaving the temple behind, I couldn’t help but reflect on the profound impact of the experience. The Hidimba Devi Temple was more than just a structure; it was a living testament to the harmonious coexistence of human creativity and the natural world. It was a reminder that architecture can be a powerful expression of cultural identity, a tangible link to the past, and a source of inspiration for the future. The temple’s unique wooden architecture, its intricate carvings, and its reverence for nature offered a refreshing contrast to the architectural traditions I was familiar with, broadening my understanding of the diverse cultural landscape of India. The image of the towering wooden pagoda, nestled amidst the towering cedars, remained etched in my mind, a symbol of the enduring power of faith and the timeless beauty of the Himalayas.

Temple

Rajput Period

Featured

80% Documented

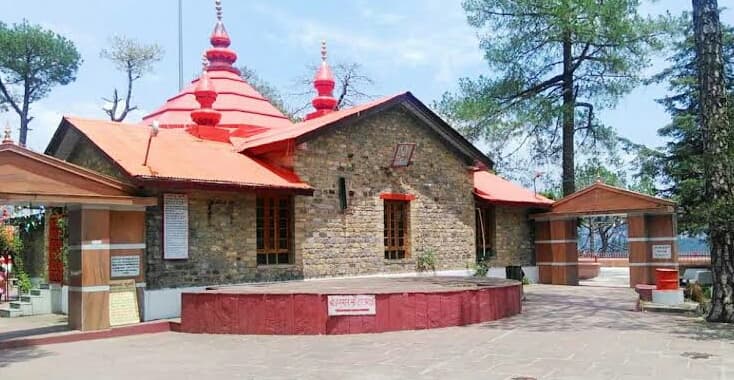

Jakhu Temple Road, Shimla, Shimla (171001), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air, scented with pine and a hint of incense, whipped around me as I ascended to the Jakhoo Temple, perched atop Shimla's highest peak. The climb itself was a pilgrimage of sorts, winding through a dense deodar forest, the path punctuated by the chattering of monkeys and the distant chime of temple bells. Having documented over 500 monuments across India, I've learned to appreciate the journey as much as the destination, and Jakhoo’s approach was particularly evocative. Emerging from the tree line, the colossal statue of Hanuman, a vibrant saffron against the cerulean sky, dominated the landscape. Its sheer scale – 108 feet tall – is breathtaking, a modern marvel seamlessly integrated into the ancient narrative of the temple. This wasn't the weathered stone and intricate carvings I’d encountered in countless other temples; this was a statement of devotion on a grand scale, a testament to faith in the digital age. The temple itself, dedicated to Lord Hanuman, is comparatively smaller, a modest structure nestled in the shadow of the giant statue. Its architecture, typical of Himalayan temples, features sloping roofs covered in slate tiles, designed to withstand the heavy snowfall. The wood carvings adorning the entrance, though worn by time and weather, depicted scenes from the Ramayana, adding a layer of narrative richness to the site. Unlike the meticulously preserved monuments I’d seen in Rajasthan or the grand temple complexes of South India, Jakhoo felt intimate, a place of active worship woven into the fabric of the local community. Inside, the air was thick with the scent of burning incense and the murmur of prayers. Devotees, a mix of locals and tourists, offered their respects to the deity, their faces illuminated by the flickering oil lamps. The walls were covered in vibrant murals depicting various incarnations of Lord Hanuman, a kaleidoscope of colours that contrasted sharply with the muted tones of the exterior. It was here, amidst the chanting and the clanging of bells, that I truly felt the pulse of the temple, a living testament to centuries of faith. What struck me most about Jakhoo, however, wasn't just its religious significance, but its unique blend of the ancient and the modern. The juxtaposition of the traditional temple architecture with the towering Hanuman statue created a fascinating dialogue between past and present. The statue, while a recent addition, didn't feel out of place; rather, it seemed to amplify the existing energy of the site, drawing the eye upwards, towards the heavens. As I photographed the temple, capturing the interplay of light and shadow on the weathered stone, I noticed the monkeys, ever-present companions on this mountaintop pilgrimage. They scampered across the rooftops, swung from the trees, and interacted with the devotees, adding a touch of playful chaos to the serene atmosphere. Their presence, while sometimes disruptive, felt integral to the Jakhoo experience, a reminder of the wildness that still clung to this sacred space. Descending the mountain, the city of Shimla spread out below me, a tapestry of buildings clinging to the hillside. The Jakhoo Temple, perched high above, felt like a silent guardian, watching over the bustling life below. It was a place where faith and nature intertwined, where ancient stories met modern expressions, and where the journey to the summit was as rewarding as the destination itself. It’s a site that will undoubtedly stay etched in my memory, another vibrant thread in the rich tapestry of India's heritage.

Temple

Dogra Period

Featured

80% Documented

Jawalamukhi Road, Kangra, Jawalamukhi (176031), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The air in Kangra Valley hummed with a palpable energy, a blend of crisp mountain air and the fervent devotion that permeated the atmosphere surrounding the Jwala Ji Temple. Nestled amidst the lower Himalayas, this ancient shrine dedicated to the Goddess Jwala Mukhi, the manifestation of eternal flame, is unlike any other I’ve encountered in my journey across India's UNESCO sites. There are no idols here, no sculpted deities. The object of veneration is the nine eternal flames that flicker from fissures in the rock, believed to be manifestations of the Goddess herself. The temple complex, while not sprawling, possesses a distinct charm. The dominant architectural style is Dogra, with intricate carvings adorning the silver-plated doors, a gift from the Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and the ornate mandap, the main prayer hall. Multi-tiered sloping roofs, typical of the region, rise above the structure, adding to its visual appeal. The courtyard, bustling with pilgrims, resonates with the rhythmic clang of bells and the chanting of mantras. The scent of incense hangs heavy in the air, a fragrant tapestry woven with the hopes and prayers of the devotees. My first encounter with the flames was a moment etched in memory. Housed within small depressions in the rock, they dance and flicker with an almost hypnotic quality. Each flame has a name – Mahakali, Annapurna, Chandi, Hinglaj, Vidhya Basni, Sarvamangala, Ambika, Anjana, and Maha Lakshmi – each representing a different aspect of the divine feminine. The flames are fueled by natural gas seeping from the earth, a geological phenomenon that adds to the mystique and reverence surrounding the site. The absence of any discernible fuel source only amplifies the belief in their divine origin. What struck me most was the palpable faith of the pilgrims. Their faces, etched with devotion, reflected a deep connection to the Goddess. From hushed whispers to fervent prayers, the atmosphere was charged with spiritual energy. I witnessed people from all walks of life, from the elderly leaning on canes to young children clinging to their parents, offering their prayers and seeking blessings. The temple serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring power of faith, a testament to the human need to connect with something larger than oneself. Beyond the main shrine, the temple complex houses several smaller shrines dedicated to other deities. I spent some time exploring these, observing the intricate details of their architecture and the unique rituals associated with each. The surrounding landscape, with its verdant hills and snow-capped peaks in the distance, added to the serene ambiance. The panoramic view from the temple courtyard is breathtaking, offering a glimpse into the natural beauty that cradles this sacred site. One of the most intriguing aspects of Jwala Ji Temple is its history, shrouded in legends and folklore. Accounts of its origins vary, with some tracing it back to the Mahabharata, while others attribute its discovery to the Mughal Emperor Akbar. The temple has witnessed the rise and fall of empires, withstanding the test of time and continuing to serve as a beacon of faith for millions. This historical depth adds another layer to the experience, making it not just a visit to a temple, but a journey through time. As I descended from the temple, the chants and the scent of incense gradually faded, but the memory of the dancing flames and the palpable devotion remained. Jwala Ji Temple is more than just a UNESCO World Heritage Site; it's a living testament to the power of faith, a place where the divine and the earthly converge, leaving an indelible mark on the soul of every visitor. It's a place I won't soon forget, a highlight of my exploration of India's rich and diverse heritage.

Temple

Dogra Period

Featured

80% Documented

Old Kangra, Kangra, Kangra (176001), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The wind whipped around me, carrying the scent of pine and a whisper of history as I stood before the imposing gates of Kangra Fort. Having explored the basalt-carved wonders of Maharashtra’s caves and the intricate details of its temples, I was eager to experience the distinct architectural language of this Himalayan fortress. Perched high on a strategic precipice overlooking the confluence of the Banganga and Majhi rivers, Kangra Fort exuded an aura of impregnable strength, a testament to its enduring legacy. My ascent through the massive gateway, locally known as the "Ranjit Singh Gate," felt like stepping back in time. The thick, fortified walls, scarred with the marks of battles fought and won, spoke volumes about the fort's tumultuous past. Each stone seemed to echo with the clash of swords and the thunder of cannons, a stark reminder of the fort’s strategic importance over centuries. Unlike the rock-cut architecture I was accustomed to in Maharashtra, Kangra’s fortifications were primarily built with dressed stone, lending it a different, more imposing character. Within the fort’s complex labyrinth, I discovered a fascinating blend of architectural styles. The influence of Rajput military architecture was evident in the sturdy ramparts, the strategically placed bastions, and the narrow, winding passages designed to confuse invaders. Yet, interspersed within this robust framework were glimpses of more delicate artistry. The crumbling remnants of palaces, adorned with faded frescoes and intricate carvings, hinted at a time of royal grandeur. The Maharani Mahal, despite its dilapidated state, still retained a certain elegance, its arched doorways and latticed windows offering glimpses of a bygone era. The Lakshmi Narayan Temple, nestled within the fort’s walls, was a striking contrast to the military structures surrounding it. Its shikhara, though damaged by past earthquakes, still reached towards the sky, a symbol of resilience and faith. The stone carvings on the temple walls, depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, were remarkably well-preserved, showcasing the skill of the artisans who crafted them. While the temple’s architecture bore some resemblance to the North Indian Nagara style, it also possessed a unique regional character, distinct from the temples I had encountered in Maharashtra. One of the most captivating aspects of Kangra Fort was its panoramic view. From the ramparts, I could see the vast expanse of the Kangra Valley stretching out before me, a patchwork of green fields and terraced hillsides. The snow-capped Dhauladhar range in the distance provided a breathtaking backdrop, adding to the fort’s majestic aura. It was easy to understand why this strategic location had been so fiercely contested throughout history. Exploring the fort’s museum, housed within the Ambika Devi Temple, provided further insights into its rich past. The collection of artifacts, including ancient coins, pottery shards, and miniature paintings, offered tangible evidence of the fort’s long and storied history. The museum also showcased the fort’s connection to the Katoch dynasty, who ruled the region for centuries. As I descended from the fort, the setting sun casting long shadows across the valley, I felt a profound sense of awe and admiration. Kangra Fort was not merely a collection of stones and mortar; it was a living testament to human resilience, ingenuity, and the enduring power of history. It stood as a stark contrast to the cave temples and intricately carved shrines of my home state, yet it resonated with the same spirit of human endeavor, a testament to the diverse tapestry of India’s cultural heritage. The echoes of battles and whispers of royal grandeur still lingered in the air, a reminder that the stories etched within these ancient walls continue to resonate across the ages.

Fort

Rajput Period

Featured

80% Documented

Lakshmi Narayan Temple Complex, Chamba (176310), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp Himalayan air vibrated with the faint clang of temple bells as I stepped into the Lakshmi Narayan Temple complex in Chamba. Nestled against the dramatic backdrop of the Dhauladhar range, this cluster of intricately carved shrines, a testament to the artistic prowess of the Chamba rulers, felt both imposing and intimate. Having documented over 500 monuments across India, I’ve developed a keen eye for architectural nuances, and Chamba’s temple complex offered a feast for the senses. The first structure that captured my attention was the Lakshmi Narayan Temple, the oldest and largest within the complex. Built primarily of wood and stone in the Shikhara style, its towering conical roof, adorned with intricate carvings of deities and mythical creatures, reached towards the azure sky. The weathered wooden panels, darkened by time and the elements, spoke of centuries of devotion and whispered stories of bygone eras. I was particularly drawn to the ornate brass doorways, their intricate floral and geometric patterns gleaming in the afternoon sun. These weren't mere entrances; they were portals to a realm of spiritual significance. As I moved deeper into the complex, I encountered a series of smaller temples, each dedicated to a different deity within the Hindu pantheon. The Radha Krishna Temple, with its delicate carvings of Krishna playing the flute, exuded a sense of playful devotion. The Shiva Temple, its stone walls adorned with depictions of the fearsome yet benevolent deity, felt palpably different, radiating an aura of quiet power. The architectural styles varied subtly, showcasing the evolution of temple architecture in the region over several centuries. Some featured sloping slate roofs, a characteristic of the local vernacular, while others echoed the Shikhara style of the main temple, creating a harmonious blend of architectural influences. One aspect that truly captivated me was the intricate woodwork. The Chamba region is renowned for its skilled woodcarvers, and their artistry is on full display throughout the complex. From the elaborately carved pillars and beams to the delicate latticework screens, every surface seemed to tell a story. I spent hours photographing these details, trying to capture the essence of the craftsmanship and the devotion that inspired it. The wood, though aged, retained a warmth and richness that contrasted beautifully with the cool grey stone. Beyond the architectural marvels, the complex pulsed with a living spirituality. Devotees moved through the courtyards, offering prayers and performing rituals. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of chants, creating an atmosphere of profound reverence. I observed a group of women circumambulating the main temple, their faces etched with devotion, their colorful saris adding vibrant splashes of color against the muted tones of the stone and wood. These weren't mere tourists; they were active participants in a centuries-old tradition, their presence adding another layer of meaning to the already rich tapestry of the site. The Lakshmi Narayan Temple complex isn't just a collection of beautiful buildings; it’s a living testament to the enduring power of faith and the artistic brilliance of a bygone era. It's a place where history, spirituality, and architecture intertwine, creating an experience that resonates deep within the soul. As I packed my equipment, preparing to leave this haven of tranquility, I felt a sense of gratitude for having witnessed this remarkable confluence of art and devotion. The images I captured, I knew, would serve as a reminder of the rich cultural heritage of Chamba and the enduring spirit of India.

Temple

Gurjara-Pratihara Period

Featured

Naggar, Kullu, Naggar (175025), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The imposing stone and timber structure of Naggar Fort, perched precariously on a cliff overlooking the Kullu Valley, whispered tales of bygone eras the moment I arrived. Having explored the Mughal architecture of Uttar Pradesh extensively, I was eager to witness this unique blend of Himalayan and Western Himalayan styles. The crisp mountain air, scented with pine, carried with it a sense of history far removed from the plains I call home. The fort, built in the 17th century by Raja Sidh Singh of Kullu, served as the royal residence and later, under British rule, as the administrative headquarters. This layered history is palpable in the architecture itself. The rough-hewn stone walls, reminiscent of the region’s vernacular architecture, speak of a time before colonial influence. These sturdy foundations contrast beautifully with the intricate woodwork of the windows and balconies, a testament to the skills of local artisans. The carvings, while less ornate than the jaali work I’m accustomed to seeing in Uttar Pradesh, possess a rustic charm, depicting deities, floral motifs, and scenes from daily life. Stepping through the heavy wooden doors of the main entrance, I was struck by the relative simplicity of the courtyard. Unlike the sprawling courtyards of Mughal forts, this one felt intimate, almost domestic. The stone paving, worn smooth by centuries of foot traffic, bore silent witness to the countless ceremonies and everyday activities that unfolded within these walls. I spent a considerable amount of time examining the Hatkot temple, dedicated to Tripura Sundari. The tiered pagoda-style roof, a distinct feature of Himalayan architecture, stood in stark contrast to the dome-shaped structures prevalent in my region. The wooden carvings on the temple exterior, though weathered by time, retained a remarkable intricacy. I noticed a recurring motif of the goddess Durga, a powerful symbol resonating with the region's warrior history. Inside the fort, the small museum offered a glimpse into the lives of the Kullu royalty. The collection, while modest, included fascinating artifacts: intricately woven textiles, ancient weaponry, and miniature paintings depicting local legends. One particular exhibit, a palanquin used by the royal family, captured my attention. The ornate carvings and rich velvet upholstery spoke of a bygone era of grandeur and ceremony. Climbing to the upper levels of the fort, I was rewarded with breathtaking panoramic views of the Kullu Valley. The Beas River snaked its way through the valley floor, flanked by terraced fields and orchards. It was easy to imagine the strategic advantage this vantage point offered the rulers of Kullu. The crisp mountain air, the distant sound of temple bells, and the panoramic vista combined to create a truly immersive experience. One aspect that particularly intrigued me was the influence of European architecture, evident in certain sections of the fort. During the British Raj, several additions and modifications were made, including the construction of a European-style kitchen and dining hall. This fusion of architectural styles, while sometimes jarring, offered a unique perspective on the region’s colonial past. It reminded me of the Indo-Saracenic architecture found in some parts of Uttar Pradesh, a similar blend of Eastern and Western influences. Leaving Naggar Fort, I felt a profound sense of connection to the history of the Kullu Valley. The fort stands as a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the region’s people, reflecting the confluence of various cultures and architectural styles. It is a place where the whispers of the past resonate strongly, offering a unique and enriching experience for anyone interested in exploring the rich tapestry of Himalayan history.

Fort

Rajput Period

Featured

80% Documented

Naina Devi, Bilaspur (174202), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp Himalayan air, scented with pine and a hint of something sacred, whipped around me as I ascended the winding path to Naina Devi Temple. Located atop a hill overlooking the Gobind Sagar reservoir in Bilaspur, Himachal Pradesh, this temple is a far cry from the rock-cut caves and ancient stone temples I'm accustomed to in my home state of Maharashtra. The journey itself sets the tone – a blend of natural beauty and palpable devotion. You can choose to hike up the steep path, a test of endurance rewarded by breathtaking views, or opt for the cable car, a swift, scenic ascent that offers glimpses of the sprawling reservoir below. Reaching the summit, I was immediately struck by the vibrant energy of the place. Unlike the hushed reverence of many ancient temples, Naina Devi buzzed with activity. Pilgrims from all walks of life, their faces etched with faith, thronged the courtyard, their murmured prayers mingling with the clanging of bells and the rhythmic chants of priests. The temple's architecture, a blend of traditional North Indian styles with a touch of modernity, immediately caught my eye. The main shrine, dedicated to the goddess Naina Devi, is a relatively new structure, rebuilt after an earthquake in 1905. Its brightly painted walls, adorned with intricate carvings and depictions of various deities, stand in stark contrast to the rugged, natural backdrop of the Himalayas. The main idol of Naina Devi, housed within the sanctum sanctorum, is a powerful representation of Shakti. Two prominent eyes, the 'Naina' that give the temple its name, dominate the image, radiating an aura of strength and protection. Unlike the meticulously sculpted stone idols I'm familiar with in Maharashtra, this representation felt more primal, more visceral. It's a simple depiction, yet it holds a profound significance for the devotees, who offer their prayers with unwavering devotion. Surrounding the main shrine are smaller temples dedicated to other deities, creating a complex of worship that caters to diverse faiths. I noticed a small shrine dedicated to Hanuman, the monkey god, a familiar figure from my explorations of Maharashtra's temples. This subtle connection, a thread of shared belief across geographical boundaries, resonated deeply with me. It highlighted the unifying power of faith, a common language spoken across the diverse landscape of India. Beyond the religious significance, the temple offers a panoramic vista that is simply breathtaking. The Gobind Sagar reservoir, a vast expanse of turquoise water nestled amidst the rolling hills, stretches out before you, creating a mesmerizing spectacle. The snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas, piercing the clear blue sky, form a majestic backdrop, adding a touch of grandeur to the already stunning landscape. I spent a considerable amount of time simply absorbing the view, feeling a sense of peace and tranquility wash over me. One aspect that particularly intrigued me was the integration of the natural landscape into the temple complex. Massive boulders, remnants of the Himalayan geology, are incorporated into the architecture, blurring the lines between the man-made and the natural. This harmonious coexistence, a hallmark of many Himalayan temples, speaks to a deep respect for the environment, a philosophy that resonates strongly with my own beliefs. My visit to Naina Devi Temple was more than just a journalistic assignment; it was a spiritual experience. It offered a glimpse into a different cultural landscape, a different way of expressing faith. While the architectural style and rituals differed significantly from what I'm accustomed to in Maharashtra, the underlying essence of devotion, the unwavering belief in a higher power, remained the same. It reinforced my belief that despite the diversity of our traditions, the human quest for spiritual meaning remains a universal constant. As I descended the hill, the clanging of temple bells fading into the distance, I carried with me not just photographs and notes, but a renewed appreciation for the power of faith and the beauty of the Himalayas.

Temple

British Colonial Period

Featured

Padam Palace Road, Shimla, Rampur Bushahr (172001), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The wind carried the scent of pine and a whisper of history as I approached Padam Palace in Rampur. Nestled amidst the imposing Himalayas in Himachal Pradesh, this former royal residence isn't as widely known as some of its Rajasthani counterparts, but it possesses a quiet charm and a unique story that captivated me from the moment I stepped onto its grounds. Unlike the flamboyant, sandstone structures of Rajasthan, Padam Palace is built of grey stone, giving it a more subdued, almost melancholic grandeur. It stands as a testament to the Bushahr dynasty, a lineage that traces its roots back centuries. The palace isn't a monolithic structure but rather a complex of buildings added over time, reflecting the evolving architectural tastes of the ruling family. The oldest section, dating back to the early 20th century, showcases a distinct colonial influence, with its arched windows, pitched roofs, and intricate woodwork. I noticed the subtle blend of indigenous Himachali architecture with European elements – a common feature in many hill state palaces. The carved wooden balconies, for instance, offered a beautiful contrast against the stark grey stone, while the sloping roofs were clearly designed to withstand the heavy snowfall this region experiences. Stepping inside, I was immediately struck by the hushed atmosphere. Sunlight streamed through the large windows, illuminating the dust motes dancing in the air. The palace is now a heritage hotel, and while some areas have been modernized for guest comfort, much of the original character has been preserved. The Durbar Hall, where the Raja once held court, is particularly impressive. The high ceilings, adorned with intricate chandeliers, and the walls lined with portraits of past rulers, evoke a sense of the power and prestige that once resided within these walls. I spent a considerable amount of time exploring the palace’s museum, housed within a section of the complex. It’s a treasure trove of artifacts, offering a glimpse into the lives of the Bushahr royals. From antique weaponry and intricately embroidered textiles to vintage photographs and handwritten documents, the collection is a fascinating testament to the region's rich history and cultural heritage. I was particularly drawn to a display of traditional Himachali jewelry, crafted with exquisite detail and showcasing the region’s unique artistic sensibilities. One of the most memorable aspects of my visit was exploring the palace gardens. Unlike the manicured lawns of many formal gardens, these felt wilder, more organic. Ancient deodar trees towered overhead, their branches laden with fragrant cones. Paths meandered through the grounds, leading to hidden nooks and offering breathtaking views of the surrounding valleys. I could easily imagine the royal family strolling through these same gardens, enjoying the crisp mountain air and the panoramic vistas. As I sat on a stone bench, overlooking the valley bathed in the golden light of the setting sun, I reflected on the stories these walls held. Padam Palace isn't just a building; it's a living testament to a bygone era, a repository of memories and traditions. It's a place where the whispers of history mingle with the rustling of leaves and the distant call of a mountain bird. While Rampur may not be on the typical tourist trail, for those seeking a glimpse into the heart of Himachal Pradesh, a visit to Padam Palace is an experience not to be missed. It offers a unique blend of architectural beauty, historical significance, and natural splendor, leaving a lasting impression on any visitor fortunate enough to discover its hidden charms. It’s a place that stays with you long after you’ve left, a reminder of the enduring power of history and the quiet beauty of the Himalayas.

Palace

British Colonial Period

Featured

Jakhoo Hill, Shimla, Shimla (171005), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp Shimla air, scented with pine and a hint of something sweeter, perhaps incense, drew me deeper into the vibrant embrace of the Sankat Mochan Temple. Nestled amidst the deodar-clad hills, overlooking the sprawling town below, the temple stands as a testament to faith and architectural ingenuity. Coming from Uttar Pradesh, a land steeped in its own rich tapestry of temples, I was curious to see how this Himalayan shrine would compare. The first thing that struck me was the temple's relative modernity. Built in the 1950s, it lacks the ancient patina of the temples I'm accustomed to back home. Yet, it possesses a distinct charm, a vibrancy that comes from being a living, breathing space of worship. The bright orange and yellow hues of the temple, set against the deep green of the surrounding forest, create a striking visual contrast. The architecture is a fascinating blend of North Indian and Himachali styles. The multi-tiered sloping roofs, reminiscent of traditional Himachali houses, are adorned with intricate carvings and colourful embellishments. The main entrance, however, features a distinctly North Indian archway, perhaps a nod to the deity enshrined within. The temple is dedicated to Lord Hanuman, the revered monkey god, a figure deeply embedded in the cultural consciousness of both Uttar Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. Inside the main sanctum, a large, imposing statue of Hanuman dominates the space. The deity is depicted in his characteristic pose, hands folded in reverence, his orange fur gleaming under the soft glow of the lamps. The air inside is thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers. Devotees from all walks of life, locals and tourists alike, thronged the temple, their faces etched with devotion. I observed a quiet reverence in their actions, a palpable sense of connection with the divine. Unlike the often elaborate rituals and ceremonies I've witnessed in Uttar Pradesh temples, the worship here seemed simpler, more direct. There was a quiet intimacy to the devotees' interactions with the deity, a sense of personal connection that transcended elaborate rituals. This, I felt, was the true essence of the temple – a space where individuals could connect with their faith in their own way, without the pressure of prescribed practices. Stepping out of the main sanctum, I explored the temple complex further. A large courtyard, paved with stone, offered stunning panoramic views of the valley below. The snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas loomed in the distance, adding a majestic backdrop to the vibrant scene. Smaller shrines dedicated to other deities dotted the courtyard, each with its own unique character and following. I noticed a small shrine dedicated to Lord Rama, Hanuman's beloved master, a testament to the enduring bond between the two figures. The presence of langurs, the grey-faced monkeys considered sacred in Hinduism, added another layer to the temple's unique atmosphere. They roamed freely within the complex, seemingly unfazed by the human activity around them. Their presence, I realized, was more than just a charming quirk; it was a tangible link to the deity enshrined within, a reminder of Hanuman's own simian form. As I descended the steps of the Sankat Mochan Temple, I carried with me more than just memories of a beautiful shrine. I carried a deeper understanding of the universality of faith, the ability of a sacred space to transcend geographical and cultural boundaries. While the architecture and rituals may differ, the underlying sentiment, the yearning for connection with the divine, remains the same, whether in the ancient temples of Uttar Pradesh or the vibrant, modern shrine nestled in the Himalayan foothills. The Sankat Mochan Temple, in its own unique way, echoed the spiritual heart of India, a heart that beats strong and true, across diverse landscapes and traditions.

Temple

British Colonial Period

Featured

Sujanpur Tira, Hamirpur (177001), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The imposing silhouette of Sujanpur Fort, perched above the Beas River in Himachal Pradesh, held a different allure than the sandstone behemoths I was accustomed to in Rajasthan. This wasn't the desert's warm embrace; this was the crisp air of the lower Himalayas, the fort a sentinel against a backdrop of verdant hills. My Rajasthani sensibilities, steeped in ornate carvings and vibrant frescoes, were immediately challenged by Sujanpur's stark, almost austere beauty. The outer walls, built of rough-hewn stone, lacked the intricate detailing of a Mehrangarh or the sheer scale of a Chittorgarh. Yet, their very simplicity spoke volumes. They whispered of a different era, a different purpose. This wasn't a palace of pleasure; this was a fortress built for resilience, a testament to the pragmatic rule of the Katoch dynasty. Stepping through the arched gateway, I felt a palpable shift in atmosphere. The outer austerity gave way to a surprising elegance within. The Baradari, a pavilion with twelve doorways, stood as the centerpiece of the inner courtyard. Its graceful arches and delicate carvings, though weathered by time, hinted at the refined tastes of the rulers who once held court here. Unlike the vibrant colours of Rajput palaces, the Baradari was adorned with subtle frescoes, predominantly in earthy tones, depicting scenes of courtly life and mythological narratives. The muted palette, I realised, complemented the surrounding landscape, creating a sense of harmony between architecture and nature. I was particularly drawn to the intricate jali work, a feature I've encountered in various forms across Rajasthan. Here, however, the jalis possessed a unique character. The patterns were less geometric, more floral, almost reminiscent of the local flora. Peering through these delicate screens, I could imagine the royal women observing the courtly proceedings, their privacy preserved while remaining connected to the pulse of the fort. The Rang Mahal, the palace's residential wing, further revealed the nuances of Katoch aesthetics. While lacking the opulence of Rajput palaces, it exuded a quiet charm. The rooms were spacious and airy, with large windows offering breathtaking views of the Beas River winding its way through the valley below. The walls, though faded, bore traces of intricate murals, depicting scenes from the Krishna Leela, a popular theme in the region. The colours, though muted now, must have once vibrated with life, adding a touch of vibrancy to the otherwise austere interiors. Exploring further, I stumbled upon the remnants of a once-grand baori, a stepped well. While not as elaborate as the Chand Baori of Abhaneri, it possessed a unique charm. The symmetrical steps, descending towards a now-dry well, spoke of a time when water was a precious commodity, carefully harvested and conserved. As I stood on the ramparts, gazing at the panoramic view of the valley below, I realised that Sujanpur Fort's beauty lay not in its grandeur, but in its understated elegance. It was a fort that had adapted to its surroundings, a fort that reflected the pragmatic yet refined sensibilities of its rulers. It was a far cry from the flamboyant palaces of my homeland, yet it held a unique charm that resonated deeply. Sujanpur Fort wasn't just a structure of stone and mortar; it was a story etched in stone, a story of resilience, adaptation, and a quiet, enduring beauty. It was a reminder that sometimes, the most captivating narratives are whispered, not shouted.

Fort

Dogra Period

Featured

80% Documented

The Mall Road, Mandi, Sundernagar (175019), Himachal Pradesh, India, Himachal Pradesh

The crisp mountain air of Sundernagar carried the scent of pine as I approached Suket Palace. Nestled amidst the verdant slopes of the Himachal Pradesh valley, this former royal residence, though not imposing in the scale I'm accustomed to seeing in South Indian temple complexes, possessed a quiet dignity. Its relatively modest size, compared to, say, the Brihadeeswarar Temple, belied the rich history it held within its walls. Built in a blend of colonial and indigenous hill architectural styles, it presented a fascinating departure from the Dravidian architecture I've spent years studying. The palace’s cream-colored façade, punctuated by dark wood balconies and intricately carved window frames, stood in stark contrast to the vibrant hues of gopurams back home. The sloping slate roof, a practical necessity in this snowy region, was a far cry from the towering vimanas of Southern temples. This adaptation to the local climate and available materials was a recurring theme I observed throughout my visit. The use of locally sourced wood, both for structural elements and decorative carvings, spoke to a sustainable building practice that resonated deeply with the traditional construction methods employed in ancient South Indian temples. Stepping inside, I was struck by the relative simplicity of the interiors. While lacking the opulent ornamentation of some Rajput palaces, Suket Palace exuded a sense of understated elegance. The spacious rooms, with their high ceilings and large windows, offered breathtaking views of the surrounding valley. The wooden floors, polished smooth by time and countless footsteps, creaked softly under my feet, whispering stories of bygone eras. I was particularly drawn to the intricate woodwork adorning the doors, window frames, and ceilings. The patterns, while distinct from the elaborate sculptures found in South Indian temples, displayed a similar level of craftsmanship and attention to detail. Floral motifs, geometric designs, and depictions of local flora and fauna intertwined to create a visual narrative unique to this region. One room, converted into a museum, housed a collection of royal artifacts, including portraits of past rulers, antique furniture, and weaponry. These objects offered a glimpse into the lives of the Suket dynasty and the cultural influences that shaped their reign. The portraits, in particular, were fascinating. The regal attire and stoic expressions of the rulers provided a stark contrast to the more stylized and often deified representations of royalty found in South Indian temple art. The palace gardens, though not as expansive as the temple gardens I'm familiar with, were meticulously maintained. Terraced flowerbeds, brimming with colorful blooms, cascaded down the hillside, creating a vibrant tapestry against the backdrop of the towering Himalayas. The integration of the natural landscape into the palace design reminded me of the sacred groves that often surround South Indian temples, highlighting the reverence for nature that transcends geographical boundaries. As I wandered through the palace grounds, I couldn't help but draw parallels between the architectural traditions of the north and south. While the styles and materials differed significantly, the underlying principles of functionality, aesthetics, and spiritual significance remained remarkably similar. The use of local materials, the adaptation to the climate, and the incorporation of symbolic motifs were all testament to the ingenuity and artistry of the builders, regardless of their geographical location. Suket Palace, in its own unique way, echoed the same reverence for history, culture, and craftsmanship that I've always admired in the grand temples of South India. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that architectural marvels can be found in the most unexpected places, each whispering its own unique story of the people and the land that shaped it.

Palace

British Colonial Period

Related Collections

Discover more heritage sites with these related collections

Explore More Heritage

Explore our research archive. Each site includes historical context, architectural analysis, construction techniques, and preservation status. Perfect for academic research and heritage studies.